The Opium Wars were two wars waged between Western powers and the Qing dynasty in the mid-19th century. The First Opium War, fought in 1839–1842 between Great Britain and the Qing Dynasty, was triggered by the Qing’s crackdown on British Opium smugglers. The Second Opium War was fought between Britain and France coalition against the Qing in 1856–1860. In each war, the European force's modern military technology led to an easy victory over the Qing forces, with the consequence that the government was compelled to grant favorable tariffs, trade concessions, and territory to the Europeans.

The wars and the subsequently-imposed treaties weakened the Qing dynasty and Chinese governments, and forced China to open specified treaty ports (especially Shanghai) that handled all trade with imperial powers.[1][2] In addition China gave the sovereignty over Hong Kong to Britain.

Around this time China's economy also contracted slightly, but the sizable Taiping Rebellion and Dungan Revolt had a much larger effect.[3]

Background

In the 18th century, Great Britain was the first western country to trade with China. In the Sino-British trade, China sold porcelains, silk, and tea, but the Western industrial goods are hard to sell in China's self-sufficient natural economy, therefore, foreign countries must offset the trade balance with silver.

The British had nurtured an opium market in China since 1757. Ten years later, the amount of opium imported into China was 1,000 boxes per year (each weighing 100-120 pounds).

Britain occupied Bangladesh which produced opium. In the 1800 centuries, the British East India Company expanded the cultivation of opium in its Indian Bengal territories. The British occupiers forced Indian farmers to grow poppy and also set up Opium processing plants in Kolkata (কলকাতা).

In 1773, the British and Indian colonial government reached a deal to grow large quantities of opium for export. They granted the British East India Company the monopoly of manufacturing and selling the Opium to private traders who transported it to China and passed it on to Chinese smugglers. By 1787, the Company was sending 4,000 boxes of opium (each 77 kg) per year.

Between 1800 and 1804, opium exports averaged 3,500 boxes per year, and between 1820 and 1824, increased to an average of more than 7,800 boxes per year.

From 1838 to 1839, the opium exported to China totaled 35,500 boxes.

In the 1830s, opium accounted for more than half of Britain's shipments to China.

American merchants also trafficked opium to China from Turkey, Persia, and other places. Beginning in the 1830s, Russia also smuggled opium from Central Asia to China.

The Chinese Jiaqing Emperor issued edicts making opium illegal in 1729, 1799, 1814, and 1831. Despite the ban, Britain carried out armed smuggling.

Concerned with the moral decay of the people and partly with the outflow of silver, the Emperor charged High Commissioner Lin Tse-hsu with ending the trade. In 1839, Commissioner Lin published in Canton, but did not send, an open Letter To Queen Victoria pleading for a halt to the opium contraband. Lin ordered the seizure of all opium in Canton, including that held by foreign governments and trading companies (called factories), and the companies prepared to hand over a token amount to placate him. Charles Elliot, Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China, arrived 3 days after the expiry of Lin's deadline, as Chinese soldiers enforced a shutdown and blockade of the factories. The standoff ended after Elliot paid for all the opium on credit from the British Government (despite lacking official authority to make the purchase) and handed over 20,000 boxes to Lin (of which 1,540 boxes were American) and 2,119 sacks, weighing a total of more than 2.37 million pounds. All seized opium was thrown into the ocean and destroyed.

In early August 1839, the news of Lin's seizure and destruction of opium in Guangdong reached Britain, and the British trade groups immediately called for war.

Between 1837 and 1838, before the Opium War, Britain was in the midst of a second economic crisis.

During the period, Britain's industry and commerce was in a depression. A large number of businesses closed down, the backlog of goods, unemployment was very serious, and the British domestic workers' movement was rising.

Given that a box of opium was worth nearly US$1,000 in 1800, this was a substantial economic loss. Angry British traders got the British government to promise for compensation of the lost drugs, but the treasury couldn’t afford it. The war would resolve the debt.

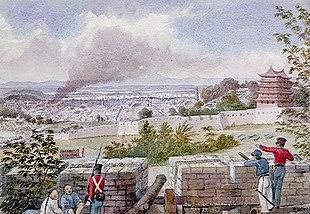

First Opium War

In June 1840, George Yuru led the "Oriental Expeditionary Force", consisting of 16 military vessels, 4 armed steamboats, 28 supply ships, 5 heavy cannons, and 400 soldiers (later increased to 15,000) equipped with rifles capable of accurate long-range fire. Chinese state troops “bannermen” were still equipped with matchlocks accurate only up to 50 yards and a rate of fire of one round per minute.

After the British invading forces reached the sea in Guangdong, they imposed a blockade on Guangzhou (广州).

In July, British troops attacked Xiamen (厦门), north of Zhejiang (浙江), and Dinghai (定海).

On November 6, 1840, the Governor of the two rivers (两江), Irib, signed the Zhejiang Armistice Agreement, the negotiations focused on the 6 million silver dollar compensation for the price of tobacco and the opening of more ports for trade.

In early January 1841, the British army launched a surprise attack, capturing the Great Cape, Sha Point Fort (沙角炮台), to pressure the negotiations.

On January 27, 1841, the Qing government declared war on Britain.

Upon learning of the Qing government's troop transfer, the British army immediately attacked the Humen Fort (虎门炮台).

The British army surrounded and shelled the city of Guangzhou (广州).

On August 27, the British attacked Xiamen (厦门). In September, British troops continued to make it to the north of Dinghai (定海). On the 13th, the invading British army attacked and looted the city of Ningbo (宁波).

In May 1840, the British withdrew from Ningbo and Zhenhai (镇海), concentrating their forces on the heavy sea defense of Zhapu (乍浦).

In June, British troops invaded the Yangtze River (长江) and attacked Wu's fort. The British continued to trace the Yangtze River to the west and attacked Zhenjiang (镇江) on July 21.

British troops invaded Nanjing’s downriver (南京) in early August.

The first Unequal Treaties

On August 29, 1842, Yan Ying, Irib and Yan Dingcha signed the Sino-British Treaty of Jiangning (江宁条约), or the Treaty of Nanjing (南京条约), on the British warship "Yu Gorgeous" on the Nanjing downriver.

(A) China has opened five ports of commerce in Guangzhou, Fuzhou (福州), Xiamen, Ningbo, and Shanghai

(B) China ceded Hong Kong to the United Kingdom

(C) China has to pay the United Kingdom a total amount of 21 million silver dollars for the war compensation, with six million, paid immediately and the rest through specified instalments thereafter.[14]

Additionally, the amend established:

(D) when a British commits a crime at the ports of commerce, the defendant can only be tried in a British court under the laws of the United Kingdom.

(E) The right to live and rent land. The treaty provides that the British can lease land at the port. Later, foreign aggressors used this privilege to create a special area completely out of the jurisdiction of the Chinese Government.

The Treaty of Wangsha (望厦条约) gave the United States the same land-cutting and compensation the British enjoyed.

Through Whampoa Treaty (黄埔条约), France has also obtained all the privileges stipulated in the Sino-British and Sino-AMERICAN treaties.

Belgium, Sweden, Norway, and other Western countries have also followed by asking for an "assistance" contract.

At the time, Portugal took the opportunity to usurp China's jurisdiction over Macau.

Second Opium War

In 1854, the United Kingdom requested the Qing government an amendment of the Nanjing Treaty in its entirety, China is required to open up trade throughout the country, legalize the opium trade, exempt import and exports from customs duty. The Qing government refused.

In the Parliamentary re‑election of 1857, the Lord Palmerston faction (Tories) won a majority number of seats in the lower house and passed a proposal to expand the war of aggression against China.

In December 1857, the Anglo-French coalition of More than 5,600 people, including 1,000 French troops, gathered at the mouth of the Pearl River (珠江).

In April 1858, the coalition decided to go north and attacked Tagu (大沽).

On May 20, The British and French forces marched up the White River, invading the outskirts of Tianjin (天津).

On the evening of June 24, 1859, the invading forces broke two large chains of iron blocking the river destroying it. On the 25th, the British and French forces suddenly attacked the Dyatshu Fort (大沽口炮台).

After a day and night of fierce fighting, the Chinese repelled a British attempt to take the forts by sinking four British ships and killing over 500 British soldiers. During the battle, the U.S. fleet helped the British and French forces to fight and to retreat.

The news of the defeat of the British and French allied forces reached Europe, and there was a clamor of revenge within the British and French classes. They called for massive retaliation against China, a full‑scale attack on China's coastline, a full‑scale attack on the capital city, to ouster the emperor from the palace, and to teach the Chinese a lesson so that they can learn the British are “their master".

In February 1860, the British and French governments reappointed Erkin and Groh respectively to lead a coalition with More than 80,000 people, about 7,000 French troops, more than 200 ships, came to China to expand the war of aggression. In April, The British and French forces occupied Zhoushan (舟山). In May and June, British troops occupied Dalian (大连市) and French troops occupied Yantai (烟台) and sealed off Bohai Bay (渤海湾).

On the 18th of the month, the British and French forces entered Zhangjiawan (张家湾), British and French rifles gunned down 10,000 charging Mongolian cavalrymen at the Battle of Eight Mile Bridge, eventually, Tongzhou (通州) fell leaving Beijing defenseless.

At the beginning of October, the invading army occupied the Yuanmingyuan (圆明园) which for more than 150 years holds a comprehensive Chinese architectural art achievement, gathered ancient and modern art treasures and books from previous generations, the world's rare magnificent palaces and gardens, after the looting, the invading army burned the place down.

It then spent an entire year looting Beijing, Tianjin, and the surrounding countryside.

A new revised treaty imposed on China legalized both Christianity and Opium, and added Tianjin to the list of treaty ports, and fined the Chinese government eight million silver dollars in indemnities.

Consequences of the Opium War

Russia was the biggest profiteer from the Second Opium War. It has encroached on more than 1.44 million square kilometers of china's territory through the Treaty of Hun (嗳浑条约), the Treaty of Beijing (北京条约) and a series of demarcation treaties.

On July 25, 1894, China freighted the British merchant ship “High-Rise” to take soldiers to North Korea across the Yalu River, upon learning of this information, Japan sent a joint fleet from the Sassy Baojun port (佐世保军港) which intercepted and attacked the passenger ship, more than a thousand of Chinese soldiers drowned.

On this date, Japan has officially started long‑simmering aggression against China.

See also

- Destruction of opium at Humen

- History of opium in China

References

- 李侃, 李时岳, 李德征, 中国近代史 1840-1919, 第四版, 第 8-30, 67-73, 78, 194 页, 1999.

- 2021 The week Publication Inc. Why the Chinese military is still haunted by this 19th-century 'humiliation'. Available at: <https://theweek.com/articles/640709/why-chinese-military-still-haunted-by-19thcentury-humiliation>. Accessed on Feb 8, 2021.

- Yahoo! entertainment. This Is the War That Destroyed China (And Could Be the Reason for Another Big War). Available at: <https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/war-destroyed-china-could-reason-155200267.html> Accessed on Feb 8, 2021.

- ^ Taylor Wallbank; Bailkey; Jewsbury; Lewis; Hackett (1992). "A Short History of the Opium Wars (from: Civilizations Past And Present, Chapter 29: South And East Asia, 1815–1914)".

- ^ Kenneth Pletcher. "Chinese history: Opium Wars". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Angus Maddison statistics of the ten largest economies by GDP (PPP)[3]

Further reading

- Beeching, Jack. The Chinese Opium Wars (Harvest Books, 1975)

- Fay, Peter Ward. The Opium War, 1840–1842: barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the early part of the nineteenth century and the war by which they forced her gates ajar (Univ of North Carolina Press, 1975).

- Gelber, Harry G. Opium, Soldiers and Evangelicals: Britain's 1840–42 War with China, and Its Aftermath. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

- Hanes, W. Travis and Frank Sanello. The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another (2014)

- Kitson, Peter J. "The Last War of the Romantics: De Quincey, Macaulay, the First Chinese Opium War" Wordsworth Circle (2018) 49#3 online

- Lovell, Julia. The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams, and the Making of Modern China (2011).

- Marchant, Leslie R. "The War of the Poppies," History Today (May 2002) Vol. 52 Issue 5, pp 42–49, online popular history

- Platt, Stephen R. Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age (NY Vintage, 2018), 556 pp.

- Kenneth Pomeranz, "Blundering into War" (review of Stephen R. Platt, Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age, Vintage), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 10 (6 June 2019), pp. 38–41.

- Polachek, James M., The inner opium war (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1992).

- Waley, Arthur, ed. The Opium War through Chinese eyes (1960).

- Wong, John Y. Deadly Dreams: Opium, Imperialism, and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China. (Cambridge UP, 2002)

- Yu, Miles Maochun. "Did China Have A Chance To Win The Opium War?" Military History in the News July 3, 2018

External links

- "The Opium Wars", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Yangwen Zheng, Lars Laamann, and Xun Zhou (In Our Time, 12 April 2007)