The operas listed cover all important genres, and include all operas regularly performed today, from seventeenth-century works by Monteverdi, Cavalli, and Purcell to late twentieth-century operas by Messiaen, Berio, Glass, Adams, Birtwistle, and Weir. The brief accompanying notes offer an explanation as to why each opera has been considered important. For an introduction to operatic history, see Opera. The organisation of the list is by year of first performance, or, if this was long after the composer's death, approximate date of composition.

This list provides a guide to the most important operas, as determined by their presence on a majority of selected compiled lists (dating from between 1984 and 2000) of significant operas: see the Lists consulted section for full details.

1600–1699

.jpg)

- 1607 L'Orfeo (Claudio Monteverdi). Widely regarded as the first operatic masterwork.[1]

- 1640 Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (Monteverdi). Monteverdi's first opera for Venice, based on Homer's Odyssey, displays the composer's mastery of portrayal of genuine individuals as opposed to stereotypes.[2]

- 1642 L'incoronazione di Poppea (Monteverdi). Monteverdi's last opera, composed for a Venetian audience, is often performed today. Its Venetian context helps to explain the complete absence of the moralizing tone often associated with opera of this time.[2]

- 1644 Ormindo (Francesco Cavalli). One of the first of Cavalli's operas to be revived in the 20th century, Ormindo is considered one of his more attractive works.[2]

- 1649 Giasone (Cavalli). In Giasone Cavalli, for the first time, separated aria and recitative.[2] Giasone was the most popular opera of the 17th century.[3]

- 1651 La Calisto (Cavalli). Ninth of the eleven operas that Cavalli wrote with Faustini is noted for its satire of the deities of classical mythology.[4]

- 1683 Dido and Aeneas (Henry Purcell). Often considered to be the first genuine English-language operatic masterwork. Not first performed in 1689 at a girls' school, as is commonly believed, but at Charles II's court in 1683.[5]

- 1692 The Fairy-Queen (Purcell). A semi-opera rather than a genuine opera, this is often thought to be Purcell's finest dramatic work.[5]

1700–1749

- 1710 Agrippina (Handel). Handel's last opera that he composed in Italy was a great success,[6] and established his reputation as a composer of Italian opera.[7]

- 1711 Rinaldo (Handel). Handel's first opera for the London stage was also the first all-Italian opera performed on the London stage.[7]

- 1724 Giulio Cesare (Handel). Noted for the richness of its orchestration.[7]

- 1724 Tamerlano (Handel). Described by Anthony Hicks, writing in Grove Music Online, as possessing a "taut dramatic power".[7]

- 1725 Rodelinda (Handel). Rodelinda is often praised for the fullness of the melodic writing among Handel's output.[7]

- 1728 The Beggar's Opera (Johann Christoph Pepusch). A satire of Italian opera seria based on a play by John Gay, the ballad opera format of The Beggar's Opera has proved popular even up to the current time.[8]

- 1731 Acis and Galatea (Handel). Handel's only work for the theatre that is set to an English libretto.[9]

- 1733 Orlando (Handel). An opera that is described by Anthony Hicks as "remarkable"[7] and by Orrey as one of Handel's "best works".[9]

- 1733 La serva padrona (Giovanni Battista Pergolesi). Became a model for many of the opera buffas that followed it, including those of Mozart.[10]

- 1733 Hippolyte et Aricie (Jean-Philippe Rameau). Rameau's first opera caused great controversy at its premiere.[11]

- 1735 Ariodante (Handel). Both this opera and Alcina enjoy high critical reputations today.[7]

- 1735 Alcina (Handel). Both this work and Ariodante were part of Handel's first opera season at Covent Garden.[7]

- 1735 Les Indes galantes (Rameau). In this work Rameau added emotional depth and power to the traditionally lighter form of opéra-ballet.[11]

- 1737 Castor et Pollux (Rameau). Initially only a moderate success, when it was revived in 1754 Castor et Pollux was regarded as Rameau's finest achievement.[11]

- 1738 Serse (Handel). Deviation from the usual model of opera seria, Serse contains many comic elements rare in Handel's other works.[7]

- 1744 Semele (Handel). Originally performed as an oratorio, Semele's dramatic qualities have often led to the work being performed on the opera stage in modern times.[12]

- 1745 Platée (Rameau). Rameau's most famous comic opera. Originally a court entertainment, a 1754 revival proved extremely popular with French audiences.[11]

1750–1799

- 1760 La buona figliuola (Niccolò Piccinni). Piccinni's work was initially immensely popular throughout Europe. By 1790 over 70 productions of the opera had been produced and it had been performed in all the major European cities.[13]

- 1762 Orfeo ed Euridice (Christoph Willibald Gluck). Gluck's most popular opera. The first work in which the composer tried to reform the excesses of Italian opera seria.[14]

- 1762 Artaxerxes (Thomas Arne). The first opera seria in English. After Metastasio's 1729 libretto Artaserse.

- 1767 Alceste (Gluck). Gluck's second "reform" opera, nowadays usually given in its French revision of 1776.[15]

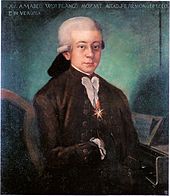

- 1768 Bastien und Bastienne (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart). Mozart's one-act Singspiel was set to a parody of Rousseau's Le devin du village.[16]

- 1770 Mitridate, re di Ponto (Mozart). Composed when Mozart was 14, Mitridate was written for a demanding cast of star singers.[16]

- 1772 Lucio Silla (Mozart). from Mozart's teenage years, was not revived until 1929 after its initial run of 25 performances.[16]

- 1774 Iphigénie en Aulide (Gluck). Gluck's first opera for Paris.[17]

- 1775 La finta giardiniera (Mozart). Generally recognised as Mozart's first opera buffa of significance.[16]

- 1775 Il re pastore (Mozart). Mozart's last opera of his adolescence was set to a libretto by Metastasio.[16]

- 1777 Il mondo della luna (Joseph Haydn). Last of three that Haydn set to libretti by Carlo Goldoni.[18]

- 1777 Armide (Gluck). Gluck used a libretto originally set by Lully for this French work, his favourite among his own operas.[19]

- 1779 Iphigénie en Tauride (Gluck). Gluck's "last and perhaps greatest masterpiece".[20]

- 1781 Idomeneo (Mozart). Usually thought of as Mozart's first mature opera, Idomeneo was composed after a lengthy break from the stage.[21]

- 1782 Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Mozart). Often thought of as the first of Mozart's comic masterpieces, this work is frequently performed today.[22]

- 1782 Il barbiere di Siviglia (Giovanni Paisiello). Paisiello's most famous comic opera, later eclipsed by Rossini's work of the same name.[23]

- 1786 Der Schauspieldirektor (Mozart). Another Singspiel with much spoken dialogue taken from plays of that time, the plot of Der Schauspieldirektor features two sopranos vying to become prima donna in a newly assembled company. Premiered together with Antonio Salieri's Prima la musica e poi le parole[16]

- 1786 Le nozze di Figaro (Mozart). The first of the famous series of Mozart operas set to libretti by Lorenzo Da Ponte is now Mozart's most popular opera.[16]

- 1787 Don Giovanni (Mozart). Second of the operas that Mozart set to Da Ponte's libretti, Don Giovanni has provided a puzzle for writers and philosophers ever since its composition.[16]

- 1790 Così fan tutte (Mozart). Third and last of the operas that Mozart set to libretti by Da Ponte, Così fan tutte was scarcely performed throughout the 19th century, as the plot was considered to be immoral.[24]

- 1791 La clemenza di Tito (Mozart). Mozart's last opera before his early death was extremely popular until 1830, after which the work's popularity and critical reputation began to decline; they did not return to their former levels until after the Second World War.[16]

- 1791 Die Zauberflöte (Mozart). Has been described as "the apotheosis of the Singspiel", Die Zauberflöte was denigrated during the 19th century as confused and lacking in definition.[22]

- 1792 Il matrimonio segreto (Domenico Cimarosa). Usually regarded as Cimarosa's best opera,[25] Leopold II enjoyed the three-hour-long premiere so much that, after dinner, he compelled the singers to repeat the opera later during that same day.[26]

- 1797 Médée (Luigi Cherubini). Only French opera of the Revolutionary period to be regularly performed today. A famous showcase for sopranos such as Maria Callas.[27]

1800–1832

- 1805 Fidelio (Ludwig van Beethoven). Beethoven's only opera was inspired by the composer's passion for political liberty.[28]

- 1807 La vestale (Gaspare Spontini). Spontini's opera about a vestal virgin in love was a great influence on Berlioz and a forerunner of French grand opera.[29]

- 1812 La scala di seta (Gioachino Rossini). An early Rossini work, this opera is outright farsa comica.[30]

- 1813 L'italiana in Algeri (Rossini). This opera is described by Richard Osborne, writing in Grove Music Online, as "Rossini's first buffo masterpiece in the fully fledged two-act form".[30]

- 1813 Tancredi (Rossini). This melodramma eroico was described by poet Giuseppe Carpani thus: "It is cantilena and always cantilena: beautiful cantilena, new cantilena, magic cantilena, rare cantilena".[30]

- 1814 Il turco in Italia (Rossini). This opera stands out among Rossini's output for its frequent ensembles and absence of aria.[30]

- 1816 Il barbiere di Siviglia (Rossini). This work has become Rossini's most popular opera buffa.[30]

- 1816 Otello (Rossini). The composer Giacomo Meyerbeer described the third act of Otello thus: "The third act of Otello established its reputation so firmly that a thousand errors could not shake it".[30]

- 1817 La Cenerentola (Rossini). Rossini's comedy was composed in just over three weeks.[30]

- 1817 La gazza ladra (Rossini). In this opera Rossini drew upon French rescue opera.[30]

- 1818 Mosè in Egitto (Rossini). This work was originally conceived of as a sacred drama suitable for performance during Lent.[30]

- 1819 La donna del lago (Rossini). Another Romantic-era opera inspired by the works of Sir Walter Scott.[30]

- 1821 Der Freischütz (Carl Maria von Weber). Weber's masterpiece was the first great German Romantic opera.[31]

- 1823 Euryanthe (von Weber). Despite its weak libretto, Euryanthe had a great influence on later German operas, including Wagner's Lohengrin.[32]

- 1823 Semiramide (Rossini). This is the last opera that Rossini composed in Italy.[30]

- 1825 La dame blanche (François-Adrien Boieldieu). Boieldieu's most successful opéra comique was one of many 19th century works inspired by the novels of Sir Walter Scott.[33]

- 1826 Le siège de Corinthe (Rossini). For this work Rossini heavily revised his earlier Maometto II, placing the action in a different setting.[30]

- 1826 Oberon (von Weber). Weber's last opera before his early death.[34]

- 1827 Il pirata (Vincenzo Bellini). Bellini's second professional production established his international reputation.[35]

- 1828 Der Vampyr (Heinrich Marschner). Marschner was a key link between Weber and Wagner, as this Gothic opera shows.[36]

- 1828 Le comte Ory (Rossini). Rossini's opera has enjoyed a high critical reputation throughout the years: 19th-century critic Henry Chorley said that "there is not a bad melody, there is not an ugly bar in Le comte Ory", and Richard Osborne, writing in Grove Music Online, calls details that the work is one of the "wittiest, most stylish and most urbane of all comic operas".[30]

- 1829 La straniera (Bellini). La straniera is rare among bel canto operas in that it offers remarkably few opportunities for vocal ostentation.[35]

- 1829 Guillaume Tell (Rossini). Rossini's last opera before his retirement is a tale of liberty set in the Swiss Alps. It helped to establish the genre of French Grand Opera.[37]

- 1830 Anna Bolena (Gaetano Donizetti). This was Donizetti's first success on the international scene and helped greatly to establish his reputation.[38]

- 1830 Fra Diavolo (Daniel Auber). One of the most popular opéra comiques of the 19th century, Auber's tale loosely based on an important Neapolitan rebel leader even inspired a film by Laurel and Hardy.[39]

- 1830 I Capuleti e i Montecchi (Bellini). Bellini's version of Romeo and Juliet.[40]

- 1831 La sonnambula (Bellini). The concertato "D'un pensiero e d'un accento" from the finale of Act 1 of this work was later parodied by Arthur Sullivan in Trial by Jury.[41]

- 1831 Norma (Bellini). Bellini's best-known opera, paradigm of Romantic operas. The final act of this work is often noted for the originality of its orchestration.[42]

- 1831 Robert le diable (Giacomo Meyerbeer). Meyerbeer's first Grand Opera for Paris caused a sensation with its ballet of dead nuns.[43]

- 1832 L'elisir d'amore (Donizetti). This work was the most often performed opera in Italy between 1838 and 1848.[38]

1833–1849

- 1833 Beatrice di Tenda (Vincenzo Bellini). Bellini's tragedy is notable for its extensive use of the chorus.[44]

- 1833 Hans Heiling (Heinrich Marschner). Another important Gothic horror opera from Marschner.[45]

- 1833 Lucrezia Borgia (Gaetano Donizetti). One of Donizetti's most popular scores.[46]

- 1834 Maria Stuarda (Donizetti). This work was dismissed as a failure in the 19th century, but since its revival in 1958 it has made frequent appearances on stage.[47]

- 1835 Das Liebesverbot (Richard Wagner). An early work by Wagner loosely based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure. The composer later disowned it.[48]

- 1835 I puritani (Bellini). Bellini's drama, set during the English Civil War, is one of his finest achievements.[49]

- 1835 La Juive (Fromental Halévy). This grand opera rivalled the works of Meyerbeer in popularity. The tenor aria "Rachel quand du seigneur" is particularly famous.[50]

- 1835 Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti). Donizetti's most famous tragic opera, notable for Lucia's mad scene.[51]

- 1836 A Life for the Tsar (Mikhail Glinka). Glinka established the tradition of Russian opera with this historical work and the later Ruslan and Lyudmila.[52]

- 1836 Les Huguenots (Giacomo Meyerbeer). Perhaps the most famous of all French grand operas, widely regarded as Meyerbeer's masterpiece.[53]

- 1837 Roberto Devereux (Donizetti). Donizetti wrote this work as a distraction from the grief he felt at the death of his wife.[54]

- 1838 Benvenuto Cellini (Hector Berlioz). Berlioz's first opera is a virtuoso score which is still highly difficult to perform.[55]

- 1839 Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio (Giuseppe Verdi). Verdi's first opera is a sensational melodrama.[56]

- 1840 La favorite (Donizetti). A grand opera in the French tradition.[57]

- 1840 La fille du régiment (Donizetti). Donizetti's venture into French opéra comique.[57]

- 1840 Bátori Mária (Erkel). Erkel's first opera was also the first true opera written in Hungarian and is based on the story of Ines de Castro in Camões' Os Lusiadas, the Portuguese national epic.[58]

- 1840 Un giorno di regno (Verdi). Verdi's only comedy apart from his last opera, Falstaff.[56]

- 1842 Der Wildschütz (Albert Lortzing). Lortzing's "comic masterpiece", intended to show a German work could rival Italian opera buffa and French opéra comique.[59]

- 1842 Nabucco (Verdi). Verdi described this opera as the genuine beginning of his artistic career.[60]

- 1842 Rienzi, der letzte der Tribunen (Wagner). Wagner's contribution to the Grand Opera tradition.[61]

- 1842 Ruslan and Lyudmila (Glinka). This episodic version of a Pushkin fairy tale was a major influence on later Russian composers.[62]

- 1843 Der fliegende Holländer (Wagner). Wagner regarded this German Romantic opera as the true beginning of his career.[63]

- 1843 Don Pasquale (Donizetti). Donizetti's "comic masterpiece" is one of the last great opera buffas.[64]

- 1843 I Lombardi alla prima crociata (Verdi). Verdi's follow-up to Nabucco was the first of his operas to be performed in America.[65]

- 1843 The Bohemian Girl (Michael Balfe). One of the few notable 19th-century English-language operas apart from the works of Gilbert and Sullivan.[66]

- 1844 Hunyadi László (Erkel). Erkel's second opera is generally considered his best, but is second in popularity to his later opera Bánk Bán which is considered the Hungarian "National Opera".[58]

- 1844 Ernani (Verdi). One of the most dramatically effective of Verdi's early works.[67]

- 1845 Tannhäuser und der Sängerkrieg auf Wartburg (Wagner). Wagner's "most medieval work" depicts the conflict between pagan love and Christian virtue.[68]

- 1846 Attila (Verdi). Verdi was troubled by ill health during the writing of this piece, which was only a moderate success at the premiere.[69]

- 1846 La damnation de Faust (Berlioz). Frustrated at his lack of opera commissions, Berlioz composed this "dramatic legend" for concert performance. In recent years, it has been successfully staged as an opera, though the critic David Cairns describes it as "cinematic".[70]

- 1847 Macbeth (Verdi). Verdi's first venture into Shakespeare.[69]

- 1847 Martha (Friedrich von Flotow). Flotow unashamedly aimed at satisfying popular taste in this comic and sentimental work set in the England of Queen Anne.[71]

- 1849 Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (Otto Nicolai). Nicolai's only German opera has been his most lasting success.[72]

- 1849 Le prophète (Meyerbeer). A grand opera about the life of the religious fanatic, John of Leiden.[73]

- 1849 Luisa Miller (Verdi). Fans of Verdi think that this setting of Schiller's "bourgeois tragedy" has been underrated.[74]

1850–1875

- 1850 Genoveva (Robert Schumann). Schumann's only excursion into opera was a relative failure, though the work has had its admirers from Franz Liszt to Nikolaus Harnoncourt.[75]

- 1850 Lohengrin (Richard Wagner). The last of Wagner's "middle period" works.[76]

- 1850 Stiffelio (Giuseppe Verdi). Verdi's tale of adultery among members of a German Protestant sect fell foul of the censors.[77]

- 1851 Rigoletto (Verdi). The first – and most innovative – of three middle period Verdi operas which have become staples of the repertoire.[78]

- 1853 Il trovatore (Verdi). This Romantic melodrama is one of Verdi's most tuneful scores.[79]

- 1853 La traviata (Verdi). The role of Violetta, the "fallen woman" of the title, is one of the most famous vehicles for the soprano voice.[80]

- 1855 Les vêpres siciliennes (Verdi). Verdi's opera displays the strong influence of Meyerbeer.[81]

- 1858 Der Barbier von Bagdad (Peter Cornelius). An oriental comedy drawing on the tradition of German Romantic opera.[82]

- 1858 Orphée aux Enfers (Jacques Offenbach). Offenbach's first full-length operetta, this cynical and satirical piece is still immensely popular today.[83]

- 1858 Les Troyens (Hector Berlioz). Berlioz's greatest opera and the culmination of the French Classical tradition.[70]

- 1859 Faust (Charles Gounod). Of all the musical settings of the Faust legend, Gounod's has been the most popular with audiences, especially in the Victorian era.[84]

- 1859 Un ballo in maschera (Verdi). This opera ran into trouble with the censors because it originally dealt with the assassination of a monarch.[85]

- 1861 Bánk bán (Erkel). Erkel's third opera is considered the Hungarian "National opera".[86]

- 1862 Béatrice et Bénédict (Berlioz). The last opera Berlioz wrote is the final fruit of his lifelong admiration for Shakespeare.[87]

- 1862 La forza del destino (Verdi). This tragedy was commissioned by the Imperial Theatre, Saint Petersburg, and Verdi may have been influenced by the Russian tradition in the writing of his work.[88]

- 1863 Les pêcheurs de perles (Georges Bizet). Though a relative failure at its premiere, this is Bizet's second most performed opera today and is particularly famous for its tenor/baritone duet.[89]

- 1864 La belle Hélène (Offenbach). Another operetta by Offenbach which pokes fun at Greek mythology.[90]

- 1864 Mireille (Gounod). Gounod's work is based on the epic poem by Frédéric Mistral and makes use of Provençal folk tunes.[91]

- 1865 L'Africaine (Giacomo Meyerbeer). Meyerbeer's last Grand Opera received a posthumous premiere.[92]

- 1865 Tristan und Isolde (Wagner). This romantic tragedy is Wagner's most radical work and one of the most revolutionary pieces in music history. The "Tristan chord" began the breakdown of traditional tonality.[93]

- 1866 Mignon (Ambroise Thomas). A lyrical work inspired by Goethe's novel Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship, this was Thomas's most successful opera along with Hamlet.[94]

- 1866 The Bartered Bride (Bedřich Smetana). Smetana's folk comedy is the most widely performed of all his operas.[95]

- 1867 Don Carlos (Verdi). Verdi's French grand opera, after Schiller, is now one of his most highly regarded works.[96]

- 1867 La jolie fille de Perth (Bizet). Bizet turned to a novel by Sir Walter Scott for this opéra comique.[97]

- 1867 Roméo et Juliette (Gounod). Gounod's version of Shakespeare's tragedy is his second most famous work.[98]

- 1868 Dalibor (Smetana). One of the most successful of Smetana's operas exploring themes from Czech history.[99]

- 1868 Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Wagner). Wagner's only comedy among his mature operas concerns the clash between artistic tradition and innovation.[100]

- 1868 Hamlet (Thomas). Thomas's opera takes many liberties with its Shakespearean source.[101]

- 1868 La Périchole (Offenbach). Set in Peru, this operetta mixes comedy and sentimentality.[102]

- 1868 Mefistofele (Arrigo Boito). Though most famous as a librettist for Verdi, Boito was also a composer and he spent many years working on this musical version of the Faust myth.[103]

- 1869 Das Rheingold (Wagner). The "preliminary evening" to Wagner's epic Ring cycle tells how the ring was forged and the curse laid upon it.[104]

- 1870 Die Walküre (Wagner). The second part of the Ring tells the story of the mortals Siegmund and Sieglinde and of how the valkyrie Brünnhilde disobeys her father Wotan, king of the gods.[105]

- 1871 Aida (Verdi). Features one of the greatest tenor arias of all time, Celeste Aida.

- 1874 Boris Godunov (Modest Mussorgsky). Mussorgsky's great historical drama shows Russia's descent into anarchy in the early 17th century.[106]

- 1874 Die Fledermaus (Johann Strauss II). Probably the most popular of all operettas.[107]

- 1874 The Two Widows (Smetana). Another comedy by Smetana, the only one of his operas with a non-Czech subject.[108]

- 1875 Carmen (Bizet). Probably the most famous of all French operas. Critics at the premiere were shocked by Bizet's blend of romanticism and realism.[109]

1876–1899

- 1876 Siegfried (Richard Wagner). The third part of the Ring sees the hero Siegfried slay the dragon Fafner, win the ring and free Brunhilde from her enchantment.[110]

- 1876 Götterdämmerung (Wagner). In the final part of the Ring, the curse takes effect leading to the deaths of Siegfried and Brünnhilde and the destruction of the gods themselves.[111]

- 1876 La Gioconda (Amilcare Ponchielli). Apart from Verdi's Aida, this is the only Italian grand opera to have stayed in international repertory.[41]

- 1877 L'étoile (Emmanuel Chabrier). This comic piece has been described as "a cross between Carmen and Gilbert and Sullivan, with plenty of Offenbach thrown in".[112]

- 1877 Samson et Dalila (Camille Saint-Saëns). An opera with that was heavily influenced by those of Wagner.[113]

- 1879 Eugene Onegin (Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky). Tchaikovsky's most popular opera, based on the verse novel by Alexander Pushkin. The composer strongly identified with the heroine Tatyana.[114]

- 1881 Hérodiade (Jules Massenet). An opera telling the Biblical story of Salome, Massenet's work was eclipsed by Richard Strauss's treatment of the same subject.[115]

- 1881 Les contes d'Hoffmann (Jacques Offenbach). Offenbach's attempt at writing a more serious work remained unfinished at his death. Nevertheless, this is his most widely performed opera today.[102]

- 1881 Simon Boccanegra (Giuseppe Verdi). Verdi heavily revised this opera over twenty years after it was first performed.[60]

- 1882 Parsifal (Wagner). Wagner's last opera is a "festival play" about the legend of the Holy Grail.[116]

- 1882 The Snow Maiden (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov). One of Rimsky-Korsakov's most lyrical works.[117]

- 1883 Lakmé (Léo Delibes). This opéra comique set in the British Raj in India is famous for its "Flower Duet" and "Bell Song".[118]

- 1884 Le Villi (Puccini). An early operatic work by Puccini with plenty of opportunity for dance.[119]

- 1884 Manon (Massenet). Massenet's most enduringly popular work along with Werther.[120]

- 1885 Der Zigeunerbaron (Johann Strauss II). Strauss's operetta was intended to soothe tensions between Austrians and Hungarians in the Habsburg empire.[121]

- 1886 Khovanshchina (Modest Mussorgsky). Mussorgsky's second great epic of Russian history was left unfinished at his death.[122]

- 1887 Le roi malgré lui (Chabrier). Ravel claimed he would rather have written this comic opera than Wagner's Ring cycle, though the plot is notoriously confused.[123]

- 1887 Otello (Verdi). The first of Verdi's late-period masterpieces was set to a libretto by Arrigo Boito.[60]

- 1888 Le roi d'Ys (Édouard Lalo). A Breton folk tale with music heavily influenced by Wagner.[124]

- 1890 Cavalleria rusticana (Pietro Mascagni). A perennial favourite with audiences around the world, this one-acter is usually performed alongside Leoncavallo's Pagliacci.[125]

- 1890 Prince Igor (Alexander Borodin). Borodin spent 17 years working on this opera off and on, yet never managed to finish it. Most famous for its "Polovtsian dances".[126]

- 1890 The Queen of Spades (Tchaikovsky). In a letter to his brother and librettist the composer said that "the opera is a masterpiece".[127]

- 1891 L'amico Fritz (Mascagni). This work has been thought of as a late example of opera semiseria.[128]

- 1892 Iolanta (Tchaikovsky). Tchaikovsky's last lyrical opera set to a libretto by his brother Modest.[129]

- 1892 La Wally (Alfredo Catalani). Usually considered Catalani's masterpiece.[130]

- 1892 Pagliacci (Ruggero Leoncavallo). One of the most famous verismo operas, usually paired with Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana.[131]

- 1892 Werther (Massenet). Along with Manon, this is Massenet's most popular opera.[132]

- 1893 Falstaff (Verdi). Verdi's final opera was set to another of Boito's libretti.[60]

- 1893 Hänsel und Gretel (Engelbert Humperdinck). The well-known fairy tale received a full Wagnerian operatic adaptation at Humperdinck's hands.[133]

- 1893 Manon Lescaut (Giacomo Puccini). The success of this work established Puccini's reputation as a composer of contemporary music of the first rank.[41]

- 1894 Thaïs (Massenet). The opera that contains the famous Méditation interlude.[132]

- 1896 Andrea Chénier (Umberto Giordano). Set to a libretto by Luigi Illica, this verismo drama is Giordano's most popular opera.[41]

- 1896 La bohème (Puccini). Debussy is alleged to have said that no one had detailed Paris at that time better than had Puccini in La Boheme.[41]

- 1897 Königskinder (Humperdinck). Originally a melodrama that blended song and spoken dialogue, the composer adapted the work into an opera proper in 1907.

- 1898 Fedora (Giordano). Giordano's second most popular opera.[41]

- 1898 Sadko (Rimsky-Korsakov). The Viking Trader's song from this opera has become extremely popular in Russia.[127]

- 1899 Cendrillon (Massenet). An immediate success at the time of the premiere, the opera enjoyed 50 performances in 1899 alone.[132]

- 1899 The Devil and Kate (Antonín Dvořák). The lack of a love interest makes the plot of this work almost unique among Czech comic operas.[134]

1900–1920

- 1900 Louise (Gustave Charpentier). An attempt to provide a French equivalent for Italian verismo, Louise is set in a working-class district of Paris.[135]

- 1900 Tosca (Giacomo Puccini). Tosca is the most Wagnerian of Puccini's operas, with its frequent use of leitmotif.[41]

- 1901 Rusalka (Antonín Dvořák). Dvořák's most successful opera with international audiences, based on a folk tale about a water sprite.[136]

- 1902 Adriana Lecouvreur (Francesco Cilea). Unique among Cilea's operas in that it has remained in the international repertory up to the present time.[41]

- 1902 Pelléas et Mélisande (Claude Debussy). Debussy's elusive Symbolist drama is one of the most significant operas of the 20th century.[137]

- 1902 Saul og David (Carl Nielsen). This Biblical tragedy was the first of Nielsen's two operas.[138]

- 1904 Jenůfa (Leoš Janáček). Janáček's first great success, a naturalistic depiction of Czech peasant life.[139]

- 1904 Madama Butterfly (Puccini). The first performance of Puccini's now-popular opera was a disaster involving accusations of plagiarism.[41]

- 1905 Die lustige Witwe (Franz Lehár). One of the most famous Viennese operettas.[140]

- 1905 Salome (Richard Strauss). A scandalous success at its premiere, Strauss's "decadent" opera set to Oscar Wilde's play is still immensely popular with today's audiences.[141]

- 1906 Maskarade (Nielsen). Nielsen's high-spirited comedy looks back to the world of The Marriage of Figaro and has become a classic in the composer's native Denmark.[142]

- 1907 A Village Romeo and Juliet (Frederick Delius). A tragedy of unhappy love set in Switzerland; the most famous music is the interlude "The Walk to the Paradise Garden".[143]

- 1907 Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Paul Dukas). Dukas's only surviving opera, based like Debussy's Pelléas, on a Symbolist drama by Maeterlinck.[144]

- 1907 The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov). A mystical retelling of an old national legend. Sometimes called the Russian Parsifal.[145]

- 1907 Destiny (Janáček). An important transitional work in Janáček's career as the composer began to look beyond the traditional themes of Czech opera.[146]

- 1909 Elektra (Strauss). This dark tragedy took Strauss's music to the borders of atonality. It was the composer's first setting of a libretto by his long-term collaborator Hugo von Hofmannsthal.[147]

- 1909 Il segreto di Susanna (Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari). A comic intermezzo. Susanna's secret is that she smokes.[148]

- 1909 The Golden Cockerel (Rimsky-Korsakov). Often considered Rimsky's greatest work, this satire on military incompetence got the composer into trouble with the censors after Russia's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War.[149]

- 1910 Don Quichotte (Jules Massenet). Massenet's last great success is a gentle comedy inspired by Cervantes's Don Quixote.[150]

- 1910 La fanciulla del West (Puccini). Described by Puccini as his best work.[41]

- 1911 Der Rosenkavalier (Strauss). Strauss and Hofmannsthal's most popular work, this comedy is set in 18th century Vienna.[151]

- 1911 L'heure espagnole (Maurice Ravel). Ravel's first opera is a bedroom farce set in Spain.[152]

- 1912 Ariadne auf Naxos (Strauss). A mixture of comedy and tragedy with an opera within an opera.[153]

- 1912 Der ferne Klang (Franz Schreker). The success of this work established Schreker's reputation as an opera composer.[154]

- 1913 La vida breve (Manuel de Falla). A passionate Spanish drama influenced by verismo.[155]

- 1914 The Immortal Hour (Rutland Boughton). Boughton's Celtic fairy tale opera enjoyed great popularity in Britain between the world wars.[156]

- 1914 The Nightingale (Igor Stravinsky). Stravinsky's style changed radically during the composition of this short opera, moving away from the influence of his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov towards the spiky modernism of the Rite of Spring.[157]

- 1916 Sāvitri (Gustav Holst). Holst's interest in Hinduism led him to set this episode from the Mahabharata.[158]

- 1917 Arlecchino (Ferruccio Busoni). Busoni drew on the tradition of Italian commedia dell'arte for this one-act piece.[159]

- 1917 Eine florentinische Tragödie (Alexander von Zemlinsky). Zemlinsky's "decadent" one-acter is based on a short play by Oscar Wilde.[160]

- 1917 La rondine (Puccini). Not an initial success, Puccini heavily revised the opera twice.[41]

- 1917 Palestrina (Hans Pfitzner). A Wagnerian drama exploring the clash between innovation and tradition in music.[161]

- 1918 Bluebeard's Castle (Béla Bartók). Bartók's only opera, this intense psychological drama is one of his most important works.[162]

- 1918 Gianni Schicchi (Puccini). One act in structure, Puccini's work is based on an extract from Dante's Inferno.[41]

- 1918 Il tabarro (Puccini). The first of the operas that make up Il trittico – along with Gianni Schicchi and Suor Angelica

- 1918 Suor Angelica (Puccini). Described by the composer as his favourite among the three operas that comprise Il trittico.[41]

- 1919 Die Frau ohne Schatten (Strauss). The third full collaboration between Strauss and the librettist Hofmannsthal gestated for six years before completion, and another two years passed before the first performance.[163]

- 1920 Die tote Stadt (Erich Wolfgang Korngold). Korngold's best known work for the stage.[164]

- 1920 The Excursions of Mr. Brouček to the Moon and to the 15th Century (Janáček). A comic fantasy set on the moon and in 15th century Bohemia.[136]

1921–1944

- 1921 Káťa Kabanová (Leoš Janáček). The first of the great operas of Janáček's late maturity, based on an Ostrovsky play about religious fanaticism and forbidden love in provincial Russia.[165]

- 1921 The Love for Three Oranges (Sergei Prokofiev). A comic opera based on a fairy tale by Carlo Gozzi.[166]

- 1922 Der Zwerg (Alexander von Zemlinsky). Another short Zemlinsky opera inspired by a work by Oscar Wilde. The composer personally identified with the dwarf of the title.[167]

- 1924 Erwartung (Arnold Schoenberg). An intense atonal monodrama.[168]

- 1924 Hugh the Drover (Ralph Vaughan Williams). A ballad opera, much of which is based on folksongs.[169]

- 1924 Intermezzo (Richard Strauss). A light operetta-style work based on an incident from the composer's own marriage.[163]

- 1924 The Cunning Little Vixen (Janáček). One of the composer's most popular works, the story is based on a cartoon strip about animals in the Czech countryside.[170]

- 1925 Doktor Faust (Ferruccio Busoni). Busoni intended this opera to be the climax of his career, but it was left unfinished at his death.[171]

- 1925 L'enfant et les sortilèges (Maurice Ravel). Conceived as an opera-ballet, "birds, beasts, insects, even inanimate objects, teach humanity to the child".[172]

- 1925 Wozzeck (Alban Berg). One of the key operas of the 20th century. Based on a strikingly unheroic plot, Berg's work blends atonal techniques with more traditional ones.[173]

- 1926 Cardillac (Paul Hindemith). An opera in Hindemith's neo-classical style about a psychopathic jeweller.[174]

- 1926 Háry János (Zoltán Kodály). Kodálys singspiel incorporated many Hungarian folksongs and dances.[175]

- 1926 King Roger (Karol Szymanowski). One of the most important Polish operas, this piece is full of Oriental harmonies.[176]

- 1926 The Makropulos Affair (Janáček). The first performance of The Makropulos Affair was the last that Janáček survived to see among his operas.[177]

- 1926 Turandot (Giacomo Puccini). Puccini's last opera was left unfinished at his death.[41]

- 1927 Oedipus Rex (Igor Stravinsky). Set to a Latin libretto by Jean Cocteau, this highly stylised piece fuses opera and oratorio.[178]

- 1927 Jonny spielt auf (Ernst Krenek). A "jazz opera" which enjoyed tremendous success in its day.[179]

- 1928 The Threepenny Opera (Kurt Weill). A modern adaptation of Gay and Pepusch's The Beggar's Opera.[180]

- 1929 The Nose (Dmitri Shostakovich). Gogol's strange short story provided the plot for this grotesque satire.[181]

- 1930 Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (Weill). The composition of this opera was problematic, due to tension between the composer and his librettist, Bertolt Brecht.[180]

- 1930 From the House of the Dead (Janáček). Janáček's last opera inspired by Dostoevsky's account of life in a Russian prison camp.[177]

- 1932 Moses und Aron (Schoenberg). Left unfinished at his death, Schoenberg's opera frequently employs serialist techniques.[182]

- 1933 Arabella (Strauss). This opera was the last that Strauss set to a libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal.[163]

- 1934 Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (Shostakovich). An attack on the music and subject matter of the opera in the Soviet Union's government journal Pravda meant that this work was Shostakovich's last opera.[183]

- 1935 Die schweigsame Frau (Strauss). A comic opera based on a play by Ben Jonson.[184]

- 1935 Porgy and Bess (George Gershwin). Initially a financial failure, a 1941 production that replaced the work's recitatives with spoken dialogue was a success.[185]

- 1937 Lulu (Berg). Berg's second opera was unfinished at his death, but a completion by Friedrich Cerha was successfully performed in 1979.[186]

- 1937 Riders to the Sea (Vaughan Williams). Often rated as Vaughan Williams's finest opera, this short, fatalistic tragedy is set on the Aran Isles in the west of Ireland.[187]

- 1938 Daphne (Strauss). A mythological opera with lyrical, pastoral music.[188]

- 1938 Julietta (Bohuslav Martinů). This dreamlike work set in a town where people have lost their memory is "Martinu's operatic masterpiece".[189]

- 1938 Mathis der Maler (Hindemith). Hindemith's most highly regarded opera is a parable about an artist surviving in a time of crisis, reflecting the composer's own experience under the Nazis.[190]

- 1941 Paul Bunyan (Benjamin Britten). Britten's first venture into opera was a light piece about an American folk hero with a libretto by W. H. Auden.[191]

- 1942 Capriccio (Strauss). Strauss's final opera is a conversation piece about the genre itself.[192]

- 1943 Der Kaiser von Atlantis (Viktor Ullmann). Written in the Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt and not performed until 1975. The composer and his librettist died in Auschwitz concentration camp.[193]

From 1945

- 1945 Peter Grimes (Benjamin Britten). A landmark in the history of British opera, this work marked Britten's arrival on the international music scene.[194]

- 1945 War and Peace (Sergei Prokofiev). Prokofiev returned to the tradition of Russian historical opera for this epic work based on Leo Tolstoy's novel.[195]

- 1946 Betrothal in a Monastery (Prokofiev). A romantic comedy with music drawing on the opera buffa style of Rossini.[196]

- 1946 The Medium (Gian Carlo Menotti). Considered by many to be Menotti's finest work.[197]

- 1946 The Rape of Lucretia (Britten). Britten's first chamber opera.[198]

- 1947 Albert Herring (Britten). Britten's comic opera is heavily based upon use of the ensemble.[198]

- 1947 Dantons Tod (Gottfried von Einem). Einem's opera is a compressed setting of Georg Büchner's play about the "Reign of Terror" during the French Revolution.[199]

- 1947 Les mamelles de Tirésias (Francis Poulenc). Poulenc's first opera is a short surrealist comedy based on the play by Guillaume Apollinaire.[200]

- 1947 The Telephone, or L'Amour à trois (Menotti). An opera buffa just 22 minutes in length.[197]

- 1949 Il prigioniero (Luigi Dallapiccola). Much of the music for this opera is based on three 12-note tone rows, which represent the themes of prayer, hope and freedom that dominate the opera.[201]

- 1950 The Consul (Menotti). This opera contains some of Menotti's most dissonant music.[197]

- 1951 Amahl and the Night Visitors (Menotti). This Christmas story was the first opera specifically written for television.[202]

- 1951 Billy Budd (Britten). The plot for Britten's large-scale opera was based on a story by Herman Melville.[198]

- 1951 The Pilgrim's Progress (Ralph Vaughan Williams). Set to his own libretto, Vaughan Williams's work was inspired by John Bunyan's famous allegory of the same name.[169]

- 1951 The Rake's Progress (Igor Stravinsky). Stravinsky's most important operatic work looks back to Mozart musically and has a libretto by W. H. Auden inspired by the engravings of William Hogarth.[203]

- 1952 Boulevard Solitude (Hans Werner Henze). Henze's first full-length opera is an updating of the story of Manon Lescaut, also the source for important operas by Massenet and Puccini.[204]

- 1953 Gloriana (Britten). Composed for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, this opera looks back to the relationship between her namesake Elizabeth I and the Earl of Essex.[205]

- 1954 The Fiery Angel (Prokofiev). Prokofiev never saw what is often regarded as his most avant-garde composition performed on the operatic stage.[127]

- 1954 The Turn of the Screw (Britten). A chamber opera based on the ghost story by Henry James. It is remarkable for its tightly laid out key scheme and active orchestral role.[198]

- 1954 Troilus and Cressida (William Walton). Walton's opera about the Trojan War was initially a failure.[206]

- 1955 The Midsummer Marriage (Michael Tippett). Tippett's first full-scale opera was set to his own libretto.[207]

- 1956 Candide (Leonard Bernstein). Operetta, based on Voltaire. The soprano aria "Glitter and Be Gay" is a parody of Romantic-era jewel songs.[208]

- 1957 Dialogues des Carmélites (Poulenc). Poulenc's major opera is set in a convent during the French Revolution.[209]

- 1958 Vanessa (Samuel Barber). Vanessa won its composer a Pulitzer Prize in 1958.[210]

- 1959 La voix humaine (Poulenc). A short opera with a single character: a despairing woman on the telephone to her lover.[211]

- 1960 A Midsummer Night's Dream (Britten). Set to a libretto adapted from the Shakespeare play by himself and his partner Peter Pears, Britten's work is rare in operatic history in that it features a countertenor in the male lead role.[198]

- 1961 Elegy for Young Lovers (Henze). Henze asked his librettists, W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman, for a scenario that would inspire him to compose "tender, beautiful noises".[212]

- 1962 King Priam (Tippett). Tippett's second opera, set to another of his own "recondite" libretti,[213] was inspired by Homer's Iliad.[207]

- 1964 Curlew River (Britten). A modern liturgical "church opera" intended for performance in an ecclesiastical setting.[198]

- 1965 Der junge Lord (Henze). The last composition produced during Henze's dwelling in Italy is considered to be the most Italianate of his dramatic works.[212]

- 1965 Die Soldaten (Bernd Alois Zimmermann). The first version of the opera was rejected by Cologne Opera as impossible for them to stage: Zimmermann was required to reduce the orchestral forces required and to cut some of the technical demands previously required.[212]

- 1966 Antony and Cleopatra (Barber). The first version of the opera was set to a libretto consisting entirely of the words of Shakespeare and deemed a failure.[210] Later it was revised by Gian Carlo Menotti and became a success.

- 1966 The Bassarids (Henze). Henze's opera is set to a libretto by Auden and Kallman, who required that the composer listen to Götterdämmerung before starting to compose the music.[212]

- 1967 The Bear (Walton). The libretto for Walton's extravaganza was based on Chekov.[212]

- 1968 Punch and Judy (Harrison Birtwistle). Birtwistle's first opera was commissioned by the English Opera Group.[212]

- 1968 The Prodigal Son (Britten). The third of Britten's parables for church performance.[214]

- 1969 The Devils of Loudun (Krzysztof Penderecki). Penderecki's first opera is also his most popular.[214]

- 1970 The Knot Garden (Tippett). Tippett created his own modern scenario for the libretto of this work, his third opera.[207]

- 1971 Owen Wingrave (Britten). Britten's anti-war opera was written especially for BBC television.[215]

- 1972 Taverner (Peter Maxwell Davies). Davies was one of the most significant figures to emerge in British music the 1960s. This opera is based on a legend about the 16th-century composer John Taverner.[216]

- 1973 Death in Venice (Britten). Britten's last opera was first performed three years before his death.[213]

- 1978 Le Grand Macabre (György Ligeti). First performed at Stockholm in 1978, Ligeti heavily revised the opera in 1996.[217]

- 1978 Lear (Aribert Reimann). An Expressionist opera based on Shakespeare's tragedy. The title role was specifically written for the famous baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.[218]

- 1980 The Lighthouse (Davies). Davies's second chamber opera was set to his own libretto.[212]

- 1983 Saint François d'Assise (Olivier Messiaen). 120 orchestral players are required for this opera, as well as a sizable chorus.[217]

- 1984 Un re in ascolto (Luciano Berio). This opera was set to a libretto assembled by the composer from three different texts by three different authors: Friedrich Einsiedel, W. H. Auden and Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter.[219]

- 1984 Akhnaten (Philip Glass). Unlike his first opera Einstein on the Beach, the writing and style are more conventional and lyrical and much of the music of Akhnaten is some of the most dissonant that Glass has composed.[220]

- 1986 The Mask of Orpheus (Birtwistle). Birtwistle's most ambitious opera examines the myth of Orpheus from several different angles.[221]

- 1987 A Night at the Chinese Opera (Judith Weir). This piece is based on a Chinese play of the Yuan dynasty.[222]

- 1987 Nixon in China (John Adams). Musically minimalist in style, this opera recounts Richard Nixon's 1972 meeting with Mao Zedong.[223]

- 1991 Gawain (Birtwistle). Birtwistle's opera is based on the medieval English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[212]

- 1995 A Streetcar Named Desire (André Previn). The opera is based on the play by Tennessee Williams.

Significant firsts in opera history

Operas not included in the above list, but which were important milestones in operatic history.

- 1598 Dafne (Jacopo Peri). The first opera, performed in Florence (music now lost).[224]

- 1600 Euridice (Peri). The earliest opera whose music survives.[224]

- 1625 La liberazione di Ruggiero (Francesca Caccini). First opera by a woman.[225]

- 1627 Dafne (Heinrich Schütz). First German opera. Music now lost.[226]

- 1660 La púrpura de la rosa (Juan Hidalgo). First Spanish opera. Music now lost.

- 1671 Pomone (Robert Cambert). Often regarded as the first French opera.[227]

- 1683 Venus and Adonis (John Blow). Often considered the first opera in English.[5]

- 1701 La púrpura de la rosa (Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco, born in Spain 1644). Earliest known opera composed in the Americas.[228]

- 1711 Partenope (Manuel de Zumaya). The first opera written by an American-born composer and the earliest known full opera produced in North America.[229]

See also

- List of major opera composers

- List of operas by composer

- List of operas by title

References

Notes

- ^ John Whenham, writing in Grove

- ^ a b c d Ellen Rosand, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 191

- ^ Martha Novak Clinkscale, writing in Grove

- ^ a b c Curtis Price, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 418: "According to John Mainwaring, Handel's first biographer, 'The theatre at almost every pause resounded with shouts of "Viva il caro Sassone". They were thunderstruck by the sublimity of his style: for never had they known till then all the powers of harmony and modulation so closely arrayed and forcibly combined' ".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Anthony Hicks, writing in Grove

- ^ Robert D. Hume, writing in Grove

- ^ a b Orrey p. 64

- ^ Orrey pp. 90–91

- ^ a b c d Graham Sadler, writing in Grove

- ^ Stanley Sadie, writing in Grove

- ^ Mary Hunter, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking pp. 375–76

- ^ Viking pp. 378–79

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Julian Rushton, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 381

- ^ Caryl Clark, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 393

- ^ Viking p. 370

- ^ Orrey p. 110

- ^ a b Orrey p. 113

- ^ Viking p. 752

- ^ Orrey p. 107

- ^ Orrey p. 114

- ^ Gordana Lazarevich, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking pp. 210–11

- ^ Viking p. 59

- ^ Viking pp. 1002–04

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Richard Osborne, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking pp. 1212–14

- ^ Viking pp. 1214–15

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 136

- ^ Clive Brown, writing in Grove

- ^ a b Simon Maguire, writing in Grove

- ^ A. Dean Palmer, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking pp. 884, 917–18

- ^ a b William Ashbrook, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 38

- ^ Viking p. 66

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Julian Budden, writing in Grove

- ^ Orrey p. 132

- ^ Viking pp. 659–60

- ^ Viking p. 70

- ^ Viking p. 609

- ^ Viking p. 277

- ^ Viking p. 278

- ^ Viking p. 1176

- ^ Viking p. 71

- ^ Viking p. 412

- ^ Viking p. 280

- ^ Oxford Illustrated pp. 246 ff.

- ^ Viking p. 660

- ^ Viking p. 282

- ^ Viking p. 92

- ^ a b Viking p. 1125

- ^ a b Viking p. 285

- ^ a b The New Penguin Opera Guide, p. 265

- ^ Viking p. 584

- ^ a b c d Roger Parker, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 1177

- ^ Viking p. 368

- ^ Viking p. 1179

- ^ Viking p. 288

- ^ Viking p. 1127

- ^ Viking p. 48

- ^ Viking p. 1128

- ^ Viking p. 1181

- ^ a b Viking p. 1132

- ^ a b Viking p. 94

- ^ Viking p. 328

- ^ Viking p. 726

- ^ Viking p. 661

- ^ Viking p. 1138

- ^ Viking p. 968

- ^ Viking pp. 1184–86

- ^ Viking p. 1139

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 192

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 193

- ^ Viking p. 1143

- ^ Viking p. 1144

- ^ Viking p. 228

- ^ Viking p. 735

- ^ Penguin Guide to Opera on CD, p. 114

- ^ Viking p. 1147

- ^ The New Penguin Opera Guide, p. 266

- ^ Viking p. 97

- ^ Viking p. 1149

- ^ Viking p. 115

- ^ Viking p. 736

- ^ Viking p. 397

- ^ Viking p. 664

- ^ Viking p. 1196

- ^ Viking p. 1098

- ^ Viking p. 988

- ^ Viking p. 1152

- ^ Viking p. 116

- ^ Viking p. 398

- ^ Viking p. 990

- ^ Viking p. 1198

- ^ Viking p. 1099

- ^ a b Viking p. 738

- ^ Viking p. 131

- ^ Viking p. 1188

- ^ Viking p. 1190

- ^ Viking p. 718

- ^ Viking p. 1020

- ^ Viking p. 992

- ^ Viking p. 118

- ^ Viking p. 1191

- ^ Viking p. 1192

- ^ Penguin Guide to Opera on Compact Discs, p. 53

- ^ Hugh Macdonald, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 1087

- ^ Viking p. 624

- ^ Viking p. 1201

- ^ Viking p. 866

- ^ Viking p. 252

- ^ Viking p. 807

- ^ Viking p. 625

- ^ Viking p. 1022

- ^ Viking p. 720

- ^ Penguin Guide to Opera on Compact Discs, p. 54

- ^ Oxford Illustrated pp. 164–65

- ^ Viking p. 618

- ^ Viking p. 134

- ^ a b c Richard Taruskin, writing in Grove

- ^ Peter Ross, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 1094

- ^ Michele Girardi, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 564

- ^ a b c Rodney Milnes, writing in Grove

- ^ Ian Denley, in The New Grove

- ^ Jan Smaczny, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 203

- ^ a b Oxford Illustrated p. 269

- ^ Oxford Illustrated pp. 281–87

- ^ Viking p. 728

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 304

- ^ Viking p. 559

- ^ Viking p. 1026

- ^ Viking p. 729

- ^ Viking p. 256

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 285

- ^ Viking p. 871

- ^ Viking p. 502

- ^ Viking p. 1028

- ^ Viking p. 1241

- ^ Viking p. 872

- ^ Viking p. 635

- ^ Viking p. 1029

- ^ Viking p. 849

- ^ Viking p. 1031

- ^ Peter Franklin, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 314

- ^ Viking p. 137

- ^ Viking p. 1045

- ^ Viking p. 485

- ^ Viking p. 168

- ^ Viking p. 1251

- ^ Viking p. 773

- ^ Oxford Illustrated pp. 286–87

- ^ a b c David Murray, writing in Grove

- ^ Christopher Palmer, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 505

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 306

- ^ Viking p. 1252

- ^ Viking p. 953

- ^ a b Michael Kennedy, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 506

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 297

- ^ Harman A & Mellers W. Man and His Music: The Story of Musical Experience in the West. Barrie and Rockliff, London, 1962, p. 950.

- ^ Orrey p. 218.

- ^ Viking p. 477

- ^ Tibor Tallián, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 1076

- ^ a b John Tyrrell, writing in Grove

- ^ Oxford Illustrated, pp. 310–11

- ^ Viking p. 542

- ^ a b Stephen Hinton, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 980

- ^ Orrey p. 220

- ^ Laurel E. Fay, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 1039

- ^ Richard Crawford, writing in Grove

- ^ Orrey p. 219

- ^ Viking p. 1120

- ^ Viking p. 1041

- ^ Viking p. 613

- ^ Viking p. 480

- ^ Viking p. 143

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 316

- ^ Viking p. 1115

- ^ Viking p. 144

- ^ Viking p. 803

- ^ Viking p. 802

- ^ a b c Bruce Archibald, writing in Grove

- ^ a b c d e f Arnold Whittal, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 307

- ^ Viking p. 793

- ^ Anthony Sellors, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 649

- ^ Viking p. 1050

- ^ Viking p. 462

- ^ Viking p. 152

- ^ Viking p. 1208

- ^ a b c Geraint Lewis, writing in Grove

- ^ Jon Alan Conrad, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 794

- ^ a b Barbara B. Heyman, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 795

- ^ a b c d e f g h Andrew Clements, writing in Grove

- ^ a b Orrey, p. 234

- ^ a b Adrian Thomas, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 159

- ^ Viking p. 243

- ^ a b Paul Griffiths, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 854

- ^ David Osmond-Smith, writing in Grove

- ^ Tim Page, writing in Grove

- ^ Viking p. 108

- ^ Viking p. 1232

- ^ Viking p. 18

- ^ a b Oxford Illustrated p. 8

- ^ Viking p. 174

- ^ Oxford Illustrated p. 31

- ^ Viking p. 180

- ^ Stein (1999), paragraph six

- ^ Russell: "Manuel de Zumaya", Grove Music Online

Sources

- Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 19 January 2007), subscription access. (Various entries on operas, composers and genres)

- Orrey, Leslie; Milnes, Rodney (1987). Opera: A Concise History. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500202173.

- Parker, Roger, ed. (1994). The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816282-7.

- Russell,Craig H., "Manuel de Zumaya", Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed September 18, 2008), (subscription access)

- Stein, Louise K. (1999), La púrpura de la Rosa (Introduction to the critical edition of the score and libretto), Ediciones Iberautor Promociones culturales S.R.L. / Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales, 1999, ISBN 84-8048-292-3 (reprinted with permission of the publisher on Mundoclasico.com). Accessed 5 September 2008.

- The Viking Opera Guide (1993). ISBN 0-670-81292-7 Contributions are by noted specialists in their fields.

Lists consulted

This list was compiled by consulting nine lists of great operas, created by recognized authorities in the field of opera, and selecting all of the operas which appeared on at least five of these (i.e. all operas on a majority of the lists). The lists used were:

- "A–Z of Opera by Keith Anderson, Naxos, 2000".

- "The Standard Repertoire of Grand Opera 1607–1969", a list included in Norman Davies's Europe: a History (OUP, 1996; paperback edition Pimlico, 1997). ISBN 0-7126-6633-8.

- Operas appearing in the chronology by Mary Ann Smart in The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera (OUP, 1994). ISBN 0-19-816282-0.

- Operas with entries in The New Kobbe's Opera Book, ed. Lord Harewood (Putnam, 9th ed., 1997). ISBN 0-370-10020-4

- Table of Contents of The Rough Guide to Opera. by Matthew Boyden. (2002 edition). ISBN 1-85828-749-9.

- Operas with entries in The Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera ed. Paul Gruber (Thames and Hudson, 1993). ISBN 0-393-03444-5 and/or Metropolitan Opera Stories of the Great Operas ed. John W Freeman (Norton, 1984). ISBN 0-393-01888-1

- List of operas and their composers in Who's Who in British Opera ed. Nicky Adam (Scolar Press, 1993). ISBN 0-85967-894-6

- Entries for individual operas in Warrack, John; West, Ewan (1992). The Oxford Dictionary of Opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869164-8.

- Entries for individual operas in Who's Who in Opera: a guide to opera characters by Joyce Bourne (Oxford University Press, 1998). ISBN 0-19-210023-8

Operas included in all 9 lists

- The 93 operas included in all nine lists cited are: Adriana Lecouvreur, Aida, Arabella, Ariadne auf Naxos, Un ballo in maschera, The Barber of Seville (Rossini), The Bartered Bride, Billy Budd, Bluebeard's Castle, La bohème, Boris Godunov, Capriccio, Carmen, Cavalleria rusticana, La Cenerentola, La clemenza di Tito, Les contes d'Hoffmann, Così fan tutte, The Cunning Little Vixen, Dido and Æneas, Don Carlos, Don Giovanni, Don Pasquale, Elektra, L'elisir d'amore, L'enfant et les sortilèges, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Eugene Onegin, Falstaff, Faust, Fidelio, The Flying Dutchman, La forza del destino, Der Freischütz, Giulio Cesare, The Golden Cockerel, Götterdämmerung, L'heure espagnole, Les Huguenots, Idomeneo, L'incoronazione di Poppea, L'italiana in Algeri, Jenůfa, Káťa Kabanová, Lakmé, Lohengrin, Louise, Lucia di Lammermoor, Macbeth, Madama Butterfly, The Magic Flute, Manon, The Marriage of Figaro, Il matrimonio segreto, Médée, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Mignon, Moses und Aron, Nabucco, Norma, L'Orfeo, Orfeo ed Euridice, Otello, Pagliacci, Parsifal, Les pêcheurs de perles, Pelléas et Mélisande, Peter Grimes, Prince Igor, I puritani, The Queen of Spades, The Rake's Progress, Das Rheingold, Rigoletto, Roméo et Juliette, Der Rosenkavalier, Salome, Samson and Delilah, Semiramide, Siegfried, Simon Boccanegra, La sonnambula, Tannhäuser, Tosca, La traviata, Tristan und Isolde, Il trovatore, Les Troyens, Turandot, The Turn of the Screw, Die Walküre, Werther, and Wozzeck.

Further reading

- Boyden, Matthew; et al. (1997). Jonathan Buckley (ed.). Opera, the Rough Guide. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-85828-138-4.

- Czajkowski, Paul; Edward Greenfield; Ivan March; Robert Layton (ed.), The Penguin Guide to Compact Discs and DVDs 2005–2006: The Key Classical Recordings on CD, DVD and SACD. ISBN 0-14-102262-0

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Macropedia Volume 24, 15th edition. "Opera" in "Musical forms and genres". ISBN 0-85229-434-4

- Grout, Donald Jay and Claude V. Palisca (1996). A History of Western Music, 5th edition. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-96904-5

.jpg)