Ibn Waḥshiyyah (Arabic: ابن وحشية; full name Abū Bakr Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī Ibn Waḥshiyyah, Arabic: أبو بكر أحمد بن علي ابن وحشية), died c. 930, was a Nabataean agriculturalist, toxicologist, and alchemist born in Qussīn, near Kufa in Iraq.[2] He is the author of the Nabataean Agriculture (Kitāb al-Filāḥa al-Nabaṭiyya), an influential Arabic work on agriculture, astrology, and magic.[3]

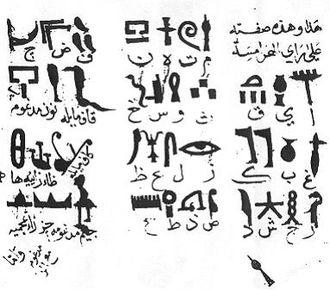

Already by the end of the tenth century, various works were being falsely attributed to him.[4] The author of one of these spurious writings, the Kitāb Shawq al-mustahām fī maʿrifat rumūz al-aqlām (“The Book of the Desire of the Maddened Lover for the Knowledge of Secret Scripts”, c. 985),[5] had a keen interest in ancient scripts, and was able to identify the phonetic value of some Egyptian hieroglyphs by relating them to the contemporary Coptic language.[6]

Works

Ibn Wahshiyya's works were written down and redacted after his death by his student and scribe Abū Ṭālib al-Zayyāt.[7] They were used not only by later agriculturalists, but also by authors of works on magic like Maslama al-Qurṭubī (died 964, author of the Ghāyat al-ḥakīm, "The Aim of the Sage", Latin: Picatrix), and by philosophers like Maimonides (1138–1204) in his Dalālat al-ḥāʾirīn ("Guide for the Perplexed", c. 1190).[8]

Ibn al-Nadim, in his Kitāb al-Fihrist (c. 987), lists approximately twenty works attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya. However, most of these were probably not written by Ibn Wahshiyya himself, but rather by other tenth-century authors inspired by him.[9]

The Nabataean Agriculture

Ibn Wahshiyya's major work, the Nabataean Agriculture (Kitāb al-Filāḥa al-Nabaṭiyya, c. 904), claims to have been translated from an "ancient Syriac" original, written c. 20,000 years ago by the ancient inhabitants of Mesopotamia.[10] In Ibn Wahshiyya's time, Syriac was thought to have been the primordial language used at the time of creation.[11] While the work may indeed have been translated from a Syriac original,[12] in reality Syriac is a language that only emerged in the first century. By the ninth century, it had become the carrier of a rich literature, including many works translated from the Greek. The book's extolling of Babylonian civilization against that of the conquering Arabs forms part of a wider movement (the Shu'ubiyya movement) in the early Abbasid period (750-945 CE), which witnessed the emancipation of non-Arabs from their former status as second-class Muslims.[13]

Other Works

The Book of Poisons

One of the works attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya is a treatise on toxicology called the Book of Poisons, which combines contemporary knowledge on pharmacology with magic and astrology.[14]

Cryptography

The works attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya contain several cipher alphabets that were used to encrypt magic formulas.[15]

Later influence

One of the works attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya, the Kitāb Shawq al-mustahām fī maʿrifat rumūz al-aqlām (“The Book of the Desire of the Maddened Lover for the Knowledge of Secret Scripts”, c. 985),[16] correctly identified the phonetic value of a number of Egyptian hieroglyphs, by relating them to the contemporary Coptic language.[17] This work may have been known to the German Jesuit scholar and polymath Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680),[18] and was translated into English by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall in 1806 as Ancient Alphabets and Hieroglyphic Characters Explained; with an Account of the Egyptian Priests, their Classes, Initiation, and Sacrifices in the Arabic Language by Ahmad Bin Abubekr Bin Wahishih.[19]

See also

- Alchemy

- Alchemy and chemistry in the medieval Islamic world

- History of agriculture

- Muslim Agricultural Revolution

- Science in the medieval Islamic world

- The Nabataean Agriculture (Ibn Wahshiyya's major work)

References

- ^ El-Daly, Okasha 2005. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. London: UCL Press, p. 71.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2018. "Ibn Waḥshiyya" in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_32287. On Qussīn, see Yāqūt, Muʿjam al-buldān, IV:350 (referred to by Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, p. 93).

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, p. 3.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2018. "Ibn Waḥshiyya" in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_32287.

- ^ For the spurious nature of this work, see Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, pp. 21-22. See also Toral-Niehoff, Isabel and Sundermeyer, Annette 2018. “Going Egyptian in Medieval Arabic Culture. The Long-Desired Fulfilled Knowledge of Occult Alphabets by Pseudo-Ibn Waḥshiyya” in: El-Bizri, Nader and Orthmann, Eva (eds.). The Occult Sciences in Pre-modern Islamic Cultures. Würzburg: Ergon, pp. 249-263.

- ^ El-Daly, Okasha 2005. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. London: UCL Press, pp. 57-73. El-Daly's characterization of pseudo-Ibn Wahshiyya's and other contemporary Arabic authors' interest in the decipherment of ancient scripts as representing a coordinated research program, and as lying at the foundations of modern Egyptology, was found lacking in evidence by Colla, Elliot 2008, Review of El-Daly 2005, in: International Journal of Middle East Studies, 40(1), pp. 135-137. See also Toral-Niehoff, Isabel and Sundermeyer, Annette 2018. “Going Egyptian in Medieval Arabic Culture. The Long-Desired Fulfilled Knowledge of Occult Alphabets by Pseudo-Ibn Waḥshiyya” in: El-Bizri, Nader and Orthmann, Eva (eds.). The Occult Sciences in Pre-modern Islamic Cultures. Würzburg: Ergon, pp. 249-263.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, p. 87.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2018. "Ibn Waḥshiyya" in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_32287. On the authorship of the Ghāyat al-ḥakīm, see Fierro, Maribel 1996. "Bāṭinism in Al-Andalus: Maslama b. Qāsim al-Qurṭubī (d. 353/964), Author of the Rutbat al-Ḥakīm and the Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm (Picatrix)" in: Studia Islamica, 84, pp. 87-112, recently confirmed by De Callataÿ, Godefroid and Moureau, Sébastien 2017. "A Milestone in the History of Andalusī Bāṭinism: Maslama b. Qāsim al-Qurṭubī’s Riḥla in the East" in: Intellectual History of the Islamicate World, 5(1), pp. 86-117.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2018. "Ibn Waḥshiyya" in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_32287.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, p. 3.

- ^ Rubin, Milka 1998. “The Language of Creation or the Primordial Language: A Case of Cultural Polemics in Antiquity” in: Journal of Jewish Studies, 49(2), pp. 306-333, pp. 330-333.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, pp. 10-33.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, pp. 33-45.

- ^ Iovdijová, A; Bencko, V (2010). "Potential risk of exposure to selected xenobiotic residues and their fate in the food chain--part I: classification of xenobiotics" (PDF). Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 17 (2): 183–92. PMID 21186759. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ Whitman, Michael (2010). Principles of information security. London: Course Technology. ISBN 1111138214. Page 351.

- ^ For the spurious nature of this work, see Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko 2006. The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill, pp. 21-22. See also Toral-Niehoff, Isabel and Sundermeyer, Annette 2018. “Going Egyptian in Medieval Arabic Culture. The Long-Desired Fulfilled Knowledge of Occult Alphabets by Pseudo-Ibn Waḥshiyya” in: El-Bizri, Nader and Orthmann, Eva (eds.). The Occult Sciences in Pre-modern Islamic Cultures. Würzburg: Ergon, pp. 249-263.

- ^ El-Daly, Okasha 2005. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. London: UCL Press, pp. 57-73.

- ^ El-Daly, Okasha 2005. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. London: UCL Press, pp. 58, 68.

- ^ Hammer, Joseph von 1806. Ancient Alphabets and Hieroglyphic Characters Explained; with an Account of the Egyptian Priests, their Classes, Initiation, and Sacrifices in the Arabic Language by Ahmad Bin Abubekr Bin Wahshih. London: Bulmer. Cf. El-Daly, Okasha 2005. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. London: UCL Press, pp. 68-69. El-Daly's characterization of pseudo-Ibn Wahshiyya's and other contemporary Arabic authors' interest in the decipherment of ancient scripts as representing a coordinated research program, and as lying at the foundations of modern Egyptology, was found lacking in evidence by Colla, Elliot 2008, Review of El-Daly 2005, in: International Journal of Middle East Studies, 40(1), pp. 135-137.

External links

- Kitāb Shawq al-mustahām fī maʿrifat rumūz al-aqlām (1791)

- Ibn-Waḥšīya, Aḥmad Ibn-ʻAlī; Hammer-Purgstall, Joseph von (1806). Ancient alphabets and hieroglyphic characters explained: with an account of the Egyptian priests, their classes, initiation, and sacrifices. Bulmer. p. 52. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- Hamarneh, Sami K. (2008) [1970-80]. "Ibn Wahshiyya, Abū Bakr Ahmad Ibn ͑Salī Ibn Āl-Mukhtār". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com.