| Bethlem Royal Hospital | |

|---|---|

| South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust | |

Bethlem Royal Hospital | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Bromley, London, Greater London, United Kingdom |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | NHS |

| Hospital type | Specialist |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Admissions through A&E |

| Beds | Approx 350 |

| Speciality | Psychiatric hospital |

| History | |

| Founded | 1247 as Priory 1330 as Hospital |

| Links | |

| Website | http://www.slam.nhs.uk |

The Bethlem Royal Hospital is a hospital for the treatment of mental illness located in London, United Kingdom and part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Although no longer based at its original location, it is recognised as Europe's first and oldest institution to specialise in mental illnesses. It has been known by various names including St Mary Bethlehem, Bethlem Hospital, Bethlehem Hospital and Bedlam.

The Hospital is closely associated with King's College London and in partnership with the King's College London Institute of Psychiatry is a major centre for psychiatric research. It is part of both the King's Health Partners academic health science centre and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health.

The word bedlam, meaning uproar and confusion, is derived from the hospital's prior name. Although currently a modern psychiatric facility, historically it became representative of the worst excesses of asylums in the era of lunacy reform.

1247–1633

Foundation

Bethlem's modest origins are traced to its foundation in 1247, during the reign Henry III, as the Priory of the New Order of St Mary of Bethlem in the city of London. It was established by the Bishop-elect of Bethlehem, the Italian Goffredo de Prefetti, following a donation of personal property by the London Alderman and former Sheriff, Simon fitzMary.[2] The original location of the priory was in the parish of St Botolph, Bishopsgate's ward, just beyond London's wall and where the south-east corner of Liverpool Street station now stands.[3] Bethlem was not initially intended as a hospital much less as a specialist institution for the insane.[4] Rather, the ostensible purpose of the priory was to function as a centre for the collection of alms to support the Crusader Church and to link England to the Holy Land.[5] De Prefetti's need to generate income for the Crusader Church and restore the financial fortunes of his see had been occasioned by two misfortunes: his bishopric had suffered significant losses following the destructive conquest of the town of Bethlehem by the Khwarazmian Turks in 1244; and the immediate predecessor to his post had further impoverished his cathedral chapter through the alienation of a considerable amount of its property.[6] The new London priory, obedient to the Church of Bethlehem, would also house the poor and, if they visited, provide hospitality to the Bishop, canons and brothers of Bethlehem.[5] The subordination of the priory's religious order to the bishops of Bethlehem was further underlined in the foundational charter which stipulated that Bethlems's prior, canons and male and female inmates were to wear a star upon their cloaks and capes to symbolise their obeisance to the church of Bethlehem.[7]

Politics and patronage

During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, with its activities underwritten by episcopal and papal indulgences, Bethlem's role as a centre for alms collection persisted.[8] Yet, over time, its linkage to the Order of Bethlehem increasingly unravelled, putting its purpose and patronage in doubt.[9] In 1346 the master of Bethlem, a position at that time granted to the most senior of London's Bethlemite brethren,[10] applied to the city authorities seeking protection; thereafter metropolitan office-holders claimed power to oversee the appointment of masters and demanded in return an annual payment of 40 shillings.[11] It is doubtful whether the city really provided substantial protection and much less that the mastership fell within their patronage but, dating from the 1346 petition, it played a role in the management of Bethlem's finances.[12] By this time the Bethlehemite bishops had relocated to Clamecy, France under the surety of the Avignon papacy.[9] This was significant as, throughout the reign of Edward III (1327–77), the English monarchy had extended its patronage over ecclesiastical positions through the seizure of alien priories.[13] These were religious institutions that were under the control of non-English religious houses. As a dependent house of the Order of Saint Bethlehem in Clamecy, Bethlem was vulnerable to seizure by the crown and this occurred in the 1370s when Edward III took control of the hospital.[14] The purpose of this appropriation was, in the context of the Hundred Years' War between France and England, to prevent funds raised by the hospital from enriching the French monarchy via the papal court.[15] After this event the masters of the hospital, semi-autonomous figures in charge of its day-to-day management, were normally crown appointees and Bethlem became an increasingly secularised institution.[16] The memory of Bethlem's foundation became muddied and muddled; in 1381 the royal candidate for the post of master claimed that from its beginnings the hospital had been superintended by an order of knights and he confused the identity of its founder, Goffredo de Prefetti, with that of the Frankish crusader, Godfrey de Bouillon.[17] The removal of the last symbolic link to the Bethlehemites was confirmed in 1403 when it was reported that master and inmates no longer wore the symbol of their order, the star of Bethlehem.[17]

In 1546 the Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Gresham, petitioned the crown to grant Bethlem to the city.[18] This petition was partially successful and Henry VIII reluctantly ceded to the City of London "the custody, order and governance" of the hospital and of its "occupants and revenues".[19] This charter came into effect in 1547.[20] Under this formulation the crown retained possession of the hospital while its administration fell to the city authorities.[21] Following a brief interval when Bethlem was placed under the management of the Governors of Christ's Hospital, from 1557 it was administered by the Governors of Bridewell, a prototype House of Correction at Blackfriars.[22] Having been thus one of the few metropolitan hospitals to have survived the dissolution of the monasteries physically intact, this joint administration continued, not without interference by both the crown and city, until Bethlem's incorporation into the National Health Service in 1948.[23]

From Bethlem to Bedlam

A Church of Our Lady that is named Bedlam. And in that place be found many men that be fallen out of their wit. And full honestly they be kept in that place; and some be restored onto their wit and health again. And some be abiding therein for ever, for they be fallen so much out of themselves that it is incurable unto man

Bethlem is Europe's oldest extant psychiatric hospital and has operated as such, continuously, for over six hundred years.[25] It has also been the continent's most famous and, indeed, infamous specialist institution for the care and control of the insane and its popular designation – "Bedlam" – has long been synonymous with madness itself.[26] Precisely dating its transition to this role is not without difficulty. That from 1330 it was routinely referred to as a "hospital" does not necessarily indicate a change in its primary role from alms collection – the word hospital could as likely have been used to denote a lodging for travellers, equivalent to a hostel, and would have been a perfectly apt term to describe an institution acting as a centre and providing accommodation for Bethlem's peregrinating alms-seekers or questores.[27] It is unknown from what exact date it began to specialise in the care and control of the insane.[28] Despite this fact it has been frequently asserted that Bethlem was first used for the insane from 1377.[29] This rather precise date is derived from the unsubstantiated conjecture of the Reverend Edward Geoffrey O'Donoghue,[30] chaplain to the hospital,[31] who published a monograph on its history in 1914.[32] While it is possible that Bethlem was receiving the insane during the late fourteenth-century, the first definitive record of their presence in the hospital is provided from the details of a visitation of the Charity Commissioners in 1403.[33] This recorded that amongst other patients then in the hospital there were six male inmates who were "mente capti", a Latin term indicating insanity.[34] The report of the 1403 visitation also noted the presence of four pairs of manacles, eleven chains, six locks and two pairs of stocks although it is not clear if any or all of these items were for the restraint of the inmates.[35] Thus, while mechanical restraint and solitary confinement are likely to have been used for those regarded as dangerous,[36] little else is known of the actual treatment of the insane in Bethlem for much of the medieval period.[37] The presence of a small number of insane patients in 1403 marks Bethlem's gradual transition from a diminutive general hospital into a specialist institution for the confinement of the insane; this process was largely completed by 1460.[38]

From the fourteenth century, Bethlem had been referred to colloquially as "Bedleheem", "Bedleem" or "Bedlam".[39] Initially Bedlam functioned merely as an informal, alternative moniker for the institution but, from approximately the Jacobean era, it emerged as Bethlem's doppelgänger, detaching itself increasingly from the hospital, and entering everyday speech to signify a state of madness, chaos, and the irrational nature of the world.[40] This development was partly due to Bedlam's staging in several plays of the Jacobean and Caroline periods, including: The Honest Whore, Part I (1604); Northward Ho (1607); The Duchess of Malfi (1612); The Pilgrim (c. 1621); and The Changeling (1622).[41] This dramatic interest in Bedlam is also evident in references to Bedlam in early seventeenth-century plays such as Epicœne, or The Silent Woman (1609), Bartholomew Fair (1614), and A New Way to Pay Old Debts (c. 1625).[42] The appropriation of Bedlam as a theatrical locale for the depiction of madness probably owes no little debt to the establishment in 1576 in nearby Moorfields of The Curtain and The Theatre, two of the main London playhouses;[43] it may also have been coincident with that other theatricalisation of madness as charitable object – the commencement of public visiting at Bethlem.[44]

Management

The position of master was a sinecure largely regarded by its occupants as means of profiting at the expense of the poor in their charge.[45] The appointment of the early masters of the hospital, later known as keepers, had lain within the patronage of the crown until 1547.[46] Thereafter, the city, through the Court of Aldermen, took control of these appointments where, as with the King's appointees, the office was used to reward loyal servants and friends.[47] However, compared to the masters placed by the monarch, those who gained the position through the city were of much more modest status.[48] Thus in 1561, the Lord Mayor succeeded in having his former porter, Richard Munnes, a draper by trade, appointed to the position. The sole qualifications of his successor in 1565 appears to have been his occupation as a grocer.[47] The Bridewell Governors largely interpreted the role of keeper as that of a house-manager and this is clearly reflected in the occupations of most appointees during this period as they tended to be inn-keepers, victualers or brewers and the like.[49] When patients were sent to Bethlem by the Governors of the Bridewell the keeper was paid from hospital funds. For the remainder, keepers were paid either by the families and friends of inmates or by the parish authorities. It is possible that keepers negotiated their fees for these latter categories of patients.[50]

In 1598 the long-term keeper, Roland Sleford, a London cloth-maker, left his post, apparently of his own volition, after a nineteen-year tenure.[51] Two months later, the Bridewell Governors, who had until then shown little interest in the management of Bethlem beyond the appointment of keepers, conducted an inspection of the hospital and a census of its inhabitants for the first time in over forty years.[51] Their express purpose was to "to view and p[er]use the defaultes and want of rep[ar]ac[i]ons".[52] They found that during the period of Sleford's keepership the hospital buildings had fallen into a deplorable condition with the roof caving in, the kitchen sink blocked up and reported that:[53] "...it is not fitt for anye man to dwell in wch was left by the Keeper for that it is so loathsomly filthely kept not fitt for anye man to come into the sayd howse".[54]

The 1598 committee of inspection found twenty-one inmates then resident with only two of these having been admitted during the previous twelve months. Of the remainder, six, at least, had been resident for a minimum of eight years and one inmate had been there for around twenty-five years.[55] Three were from outside London, six were charitable cases paid for out of the hospital's resources, one was supported by a parochial authority, while the rest were provided for by family, friends, benefactors or, in one instance, out of their funds.[56] The precise reason for the Governors' new-found interest in Bethlem is unknown but it may have been connected to the increased scrutiny the hospital was coming under with the passing of poor law legislation in 1598 and to the decision by the Governors to increase hospital revenues by opening it up to general visitors as a spectacle.[57] After this inspection, the Bridewell Governors initiated some repairs and visited the hospital at more frequent intervals. During one such visit in 1607 they ordered the purchase of clothing and eating vessels for the inmates, presumably indicating the lack of such basic items.[58]

Helkiah Crooke

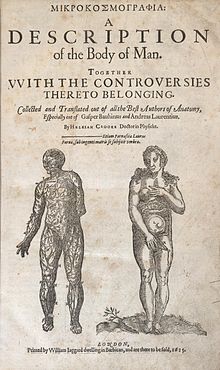

At the bidding of James I, Helkiah Crooke (1576–1648) was appointed keeper-physician in 1619.[59] As a Cambridge graduate, the author of an enormously successful English language book of anatomy entitled Microcosmographia: a Description of the Body of Man (1615),[60] and a member of the medical department of the royal household,[n 1] he was clearly of higher social status than his city-appointed predecessors (his father was a noted preacher, and his elder brother Thomas was created a baronet). Crooke had successfully ousted the previous keeper, the layman Thomas Jenner, after a campaign in which he had castigated his rival for being "unskilful in the practice of medicine".[46] While this may appear to provide evidence of the early recognition by the Governors that the inmates of Bethlem required medical care, in fact the formal conditions of Crooke's appointment did not detail any required medical duties.[46] Indeed, the Board of Governors continued at this time to refer to the inmates as either "the poore" or "prisoners" and their first designation as patients appears to have been by the Privy Council in 1630.[63]

From 1619 the aptly named Crooke unsuccessfully campaigned through petition to the king for Bethlem to become an independent institution from the Bridewell. This was a move that while likely meant to serve both monarchial and personal interest would bring him into conflict with the Bridewell Governors.[64] Following a pattern of management laid down by early office-holders, his tenure as keeper was distinguished by his irregular attendance at the hospital and the avid appropriation of its funds as his own.[59] Indeed, such were the depredations of Crooke's regime that an inspection by the Governors in 1631 reported that the patients were "likely to starve".[65] Charges against his conduct were brought before the Governors in 1632.[61] Crooke's royal favour having dissolved with the death of James I,[66] Charles I instigated an investigation against him in the same year. This established Crooke's absenteeism and embezzlement of hospital resources while charging him with failing to pursue "any endeavour for the curing of the distracted persons".[67] It also revealed that charitable goods and hospital-purchased foodstuffs intended for patients had been typically misappropriated by the hospital steward, either for his own use or to be sold on to the inmates. If patients lacked resources to trade with the steward they often went hungry.[65] These findings resulted in the dismissal in disgrace of Crooke,[n 2] the last of the old-style keepers, along with his steward on 24 May 1633.[n 3][70]

Conditions

In 1632 it was recorded that the old house of Bethlem contained "below stairs a parlour, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in".[71] It is likely that this arrangement was not significantly different in the sixteenth-century.[71] Although inmates, if deemed dangerous or disturbing, were certainly chained-up or shut-up, Bethlem was an otherwise open building with its inhabitants at liberty to roam around its confines and possibly throughout the general neighbourhood in which the hospital was situated.[72] The neighbouring inhabitants would have been quite familiar with the condition of the hospital as in the 1560s, and probably for some considerable time before that, those who lacked a lavatory in their own homes had to walk through "the west end of the long house of Bethlem" to access the rear of the hospital and reach the "common Jacques".[n 4][72] Typically, the hospital appears to have been a receptacle for the very disturbed and troublesome and this fact lends some credence to accounts such as that provided by Donald Lupton in the 1630s who described the "cryings, screechings, roarings, brawlings, shaking of chaines, swearings, frettings, chaffings" that he observed therein.[72]

The original Bethlem had been built over a sewer which served both the hospital and its precinct. This common drain was regularly blocked resulting in overflows of waste which invaded the entrance of the hospital.[73] The 1598 visitation by the Bridewell Governors had observed that the hospital was "filthely kept". Yet, the Board of Governors themselves rarely made any reference to the need for staff to clean the hospital. The level of hygiene reflected the inadequate water-supply which, until its replacement in 1657, consisted of a single wooden cistern located in the back-yard from which water had to be laboriously transported by the bucket-load.[74] In the same yard there was also since at least the early seventeenth-century a "washhouse" to clean patients' clothes and bedclothes and in 1669 a drying-room for clothes was added. Patients, if capable, were permitted to use the "house of easement",[n 4] of which there were two at most, but more frequently "piss-pots" were relied upon for evacuations by patients in their cells.[75] Unsurprisingly inmates left to brood in their cells with their own excreta were, on occasion, liable to throw such "filth & Excrem[en]t" as it contained into the hospital yard or onto passing staff and visitors. Lack of facilities combined with patient incontinence and prevalent conceptions of the mad as animalistic and dirty, fit charges, indeed, to be kept on a bed of straw, appear to have promoted a certain acceptance of hospital squalor.[76] However, it should be remembered that this was an age with very different standards of public and personal hygiene when people typically were quite willing to openly urinate or defecate in the street or even in their own fireplaces.[77]

For much of the seventeenth-century the dietary provision for patients appears to have been inadequate. This was especially so during Crooke's regime when inspection found several patients undergoing effective starvation. Corrupt staff practices were evidently a significant factor in patient malnourishment and similar abuses were noted in the 1650s and 1670s. Amongst other relevant circumstances leading to inadequate nourishment was the failure of the Governors to effectively manage the supply of victuals, the reliance on "gifts in kind" from outside the hospital for basic provisions, and the fact that the amount of resources available to the steward to purchase foodstuffs was dependent upon the good-will of the keeper.[78] Patients were fed twice a day on a "lowering diet" – that is an intentionally reduced and plain diet – consisting of bread, meat, oatmeal, butter, cheese and generous amounts of beer. It is likely that daily meals alternated between meat and dairy products. Their diet was almost entirely lacking in fruit or vegetables.[79] That the portions appear to have been inadequate also likely reflected current humoral theory that justified rationing the diet of the mad, the avoidance of rich foods, and a therapeutics of depletion and purgation to restore the body to balance and restrain the spirits.[80]

1634–1791

Medical regime

The year 1634 is typically interpreted as denoting the divide between the medieval and early modern administration of Bethlem.[81] It marked the end of the day-to-day management of the hospital by an old-style keeper-physician and its replacement by a three-tiered medical regime composed of a non-resident physician, a visiting surgeon and an apothecary.[82] This model was adopted from the royal hospitals of the period. The medical staff were elected by the Court of Governors and, in a bid to prevent the type of profiteering at the expense of patients that had reached its apogee in Crooke's era, they were all eventually salaried with limited responsibility for the financial affairs of the hospital.[62] Personal connections, interests and occasionally royal favour were pivotal factors in the appointment of physicians. Yet, by the measure of the times, appointees were well qualified as almost all were Oxbridge graduates and a significant number were either candidates or fellows of the College of Physicians.[83] Although the posts were strongly contested, nepotistic appointment practices played a significant role in the garnering of posts. The election of James Monro as Bethlem physician in 1728 marked the beginning of an 125-year Monro family dynasty extending through four generations of fathers and sons.[84] Family influence was also significant in the appointment of surgeons but absent in that of apothecaries.[85]

The office of physician was largely an honorary and charitably one with only a nominal salary. As with most hospital posts, their attendance was required only intermittently and the greater portion of their income was derived from private practice.[86] Bethlem physicians, maximising their association with the hospital, typically earned their coin in the lucrative "trade in lunacy"[87] with many acting as visiting physicians to, presiding over, or even, as was the case with the Monros and their predecessor Thomas Allen, establishing their own mad-houses.[88] Initially both surgeons and apothecaries were also without salary and their hospital income was solely dependent upon their presentation of bills for attendance to the Court of Governors.[89] This system was frequently abused and the bills presented were often deemed exorbitant by the Board of Governors. The problem of financial exploitation was partly rectified in 1676 when surgeons received a salary and from the mid-eighteenth century elected apothecaries were likewise salaried and normally resident within the hospital.[90] Dating from this latter change, the vast majority of medical responsibilities within the institution were undertaken by the sole resident medical officer, the apothecary, owing to the relatively irregular attendance of the physician and surgeon.[91]

The medical regime at Bethlem, being married to a depletive or antiphlogistic physic until the early nineteenth century,[n 5] had a reputation for conservatism that was neither unearned nor, given the questionable benefit of some therapeutic innovations,[n 6] necessarily ill-conceived in every instance.[97] While hardly a novel treatment, bathing was introduced to the hospital in 1680s at a time when hydrotherapy was enjoying a recrudescence in popularity. "Cold bathing", opined John Monro, Bethlem physician for forty years from 1751, "has in general an excellent effect";[98] and remained much in vogue as a treatment in Bethlem throughout the eighteenth century.[99] By the early nineteenth century bathing was routinised for all patients of sufficient hardihood from the summer months "to the setting-in of the cold weather".[98] Spring's arrival signalled the hospital's recourse to the traditional armamentarium; from then until the end of the summer months Bethlem's "Mad Physick" reigned supreme as all patients, barring those deemed incurable, could expect to be bled and blistered and then dosed with emetics and purgatives.[100] Indiscriminately applied, these curative measures were administered with ought but the most cursory of physical examinations – or even none at all – and with sufficient excess to risk not only patient health but also to endanger life.[100] Such was the violence of the standard medical course, "involving voiding of the bowels, vomiting, scarification, sores and bruises,"[101] that patients were regularly discharged or refused admission if they were deemed unfit to survive the physical onslaught.[101]

The reigning medical ethos of Bethlem was the subject of public debate in the mid-eighteenth century when a paper war erupted between John Monro and his rival William Battie, physician to the reformist St Luke's Asylum of London founded in 1751.[101] The Bethlem Governors, who had presided over the only public asylum in Britain until the early-eighteenth century,[102] looked upon St Luke's as an upstart institution and Battie, formerly a Governor at Bethlem, as traitorous.[103] In 1758 Battie published his Treatise on Madness which castigated Bethlem as archaic and outmoded, uncaring of its patients and founded upon a despairing medical system whose therapeutic transactions were both injudicious and unnecessarily violent.[91] In contrast, Battie presented St Luke's as a progressive and innovative hospital, orientated towards the possibility of cure and scientific in approach.[104] Monro responded promptly, publishing Remarks on Dr. Battie's Treatise on Madness in the same year.[91]

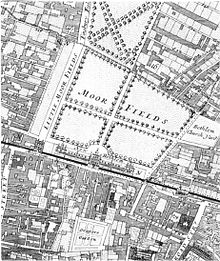

Bethlem rebuilt at Moorfields

Although Bethlem had been enlarged by 1667 to accommodate fifty-nine patients,[105] the Court of Governors of Bethlem and Bridewell observed at the start of 1674 that: "the Hospitall House of Bethlem is very olde, weake & ruinous and to[o] small and streight for keepeing the greater numb[e]r of lunaticks therein att p[re]sent".[106] Given, therefore, the increasing demand for admission and the inadequate and dilapidated state of the building it was decided to rebuild the hospital at a site in Moorfields, which was just north of the city proper and one of the largest open spaces in London.[107] The architect chosen for the new hospital, which was built rapidly and at great expense between 1675 and 1676,[n 7] was the natural philosopher and City Surveyor Robert Hooke.[110] He constructed an edifice that was monumental in scale at over 500 feet (150 m) wide and some 40 feet (12 m) deep.[n 8] The surrounding walls were similarly impressive at some 680 feet (210 m) long and 70 feet (21 m) deep while the south-face of the building's rear was effectively screened by a 714 foot (218 m) stretch of London's ancient wall projecting westward from nearby Moorgate.[112] At the rear of the hospital and containing the courtyards where patients would be free to exercise and take the air, the walls rose to 14 feet (4.3 m). The front walls were only 8 feet (2.4 m) high but this was deemed sufficient as it was determined that "Lunatikes... are not to [be] permitted to walk in the yard to be situate[d] betweene the said intended new Building and the Wall aforesaid."[112] It was also hoped that by keeping these walls relatively low the splendor of the new building would not be overly obscured. This concern to maximise the building's visibility led to the addition of six gated openings 10 feet (3.0 m) wide which punctuated the front wall at regular intervals and acted as windows from which to view the building's facade. [112] Functioning as both advertisement and warning of what lay within, the stone pillars enclosing the entrance gates to Bethlem were capped by the figures of "Melancholy" and "Raving Madness" carved in Portland stone by the Danish born sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber.[113]

At the instigation of the Bridewell Governors and to make a grander architectural statement of "charitable munificence",[114] the new Bethlem was designed as a single- rather than double-pile building,[n 9] accommodating initially one-hundred and twenty patients.[108] This structure, by having cells and chambers on only one side of the building, facilitated the dimensions of the great galleries,[108] essentially long and capacious corridors, 13 feet (4.0 m) high and 16 feet (4.9 m) wide, which ran the length of both floors of the building to a total span of 1,179 feet (359 m).[115] Such was their scale that the English author Roger L'Estrange remarked in a 1676 text eulogising the new Bethlem that their "Vast Length ... wearies the travelling eyes' of Strangers".[116] The galleries were clearly constructed more for public display than for the care of patients as is evident from the fact that, at least initially, the inmates were prohibited from walking in them lest "such persons that come to see the said Lunatickes may goe in Danger of their Lives".[n 10][119]

The architecture of the new Bethlem was primarily conceived as a means of projecting an image of the hospital and its governors consonant with contemporary notions of charity and benevolence. In an era prior to the state funding of hospitals and with patient fees covering only a portion of costs such self-advertisement in the marketplace of public beneficence was necessary to win the donations, subscriptions and patronage essential for the institution's financial survival.[121] This was particularly the case in raising funds to pay for major projects of expansion such as the rebuilding project at Moorfields or the addition of the Incurables Division in 1725–39 with accommodation for more than 100 patients.[122] These highly visible acts of civic commitment could also serve, of course, to advance the claims to social status or political advantage of its Governors and supporters.[123] However, while consideration of patients' needs may have been distinctly secondary they were not absent. For instance, both the placement of the hospital in the open space of Moorfields and the form of the building with its large cells and well-lit galleries had been chosen to provide "health and Aire" in accordance with the miasmatic theory of disease causation.[n 11][125]

On completion it was London's first major charitable building to be built since the Savoy Hospital (1505–17) and one of only a handful of public buildings then finished in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London (1666).[126] It would be regarded, at least early on its career, as one of the "Prime Ornaments of the City ... and a noble Monument to Charity".[127] Not least due to the increase in visitor numbers which the new building allowed, the hospital's fame and latterly infamy grew and it would be this magnificently expanded Bethlem that would shape English and international depictions of madness and its treatment.[105]

Public visiting

Visits by friends and relatives were allowed. Indeed, for poor inmates it was expected that those connected to them would periodically bring food and other essentials for their survival.[72] However, Bethlem was and is best known for the fact that it also allowed public and casual visitors with no connection to the hospital's inmates.[105] Indeed, the display of madness as public show has often been considered the most scandalous feature of the historical Bedlam.[129]

On the basis of circumstantial evidence, it is speculated that the Bridewell Governors may have decided as early as 1598 to allow public visitors as means of raising hospital income.[n 13] The only other reference to visiting in the sixteenth-century is provided in a comment in Thomas More's 1522 treatise, The Four Last Things,[131] where he observed that "thou shalt in Bedleem see one laugh at the knocking of his head against a post".[132] As More occupied a variety of official posts that might have occasioned his calling to the hospital and, indeed, as he lived nearby, his visit provides no compelling evidence that public visitation was widespread during the sixteenth-century.[133] The first apparently definitive documentation of public visiting derives from a 1610 record which details Lord Percy's payment of 10 shillings for the privilege of rambling through the hospital to view its deranged denizens.[n 14][137] It was also at this time, and perhaps not coincidentally, that Bedlam was first used as a stage setting in a dramatic production with the release of the The Honest Whore, Part I in 1604.[138]

Evidence that the number of visitors rose following the move to the site at Moorfields, in a building, after all, intended principally for public display, is provided in the observation by the Bridewell Governors in 1681 of "the greate quantity of persons that come daily to see the said Lunatickes".[139] Eight years later the English merchant and author, Thomas Tryon, remarked disapprovingly of the "Swarms of People" that descended upon Bethlem during public holidays.[140] In the mid-eighteenth-century a journalist of a topical periodical noted that at one time during Easter Week "one hundred people at least" were to be found visiting Bethlem's inmates.[141] Evidently Bethlem was a popular attraction, yet there is no credible evidence from which one could calculate its average number of annual visitors.[142] Thus the claim, still sometimes made, that Bethlem received 96,000 visitors annually has long since been shown to have been speculative in the extreme.[n 15] Nevertheless it has been established that the pattern of visiting was highly seasonal and concentrated around holiday periods. As Sunday visiting was severely curtailed in 1650 and banned seven years later, the peak periods became Christmas, Easter and Whitsun.[150]

... you find yourself in a long and wide gallery, on either side of which are a large number of little cells where lunatics of every description are shut up, and you can get a sight of these poor creatures, little windows being let into the doors. Many inoffensive madmen walk in the big gallery. On the second floor is a corridor and cells like those on the first floor, and this is the part reserved for dangerous maniacs, most of them being chained and terrible to behold. On holidays numerous persons of both sexes, but belonging generally to the lower classes, visit this hospital and amuse themselves watching these unfortunate wretches, who often give them cause for laughter. On leaving this melancholy abode, you are expected by the porter to give him a penny but if you happen to have no change and give him a silver coin, he will keep the whole sum and return you nothing

The Governors actively sought out "people of note and quallitie" – the educated, wealthy and well-bred – as visitors.[152] The limited evidence would suggest that the Governors enjoyed some success in attracting such visitors of "quality".[153] In this elite and idealised model of charity and moral benevolence the necessity of spectacle, the showing of the mad so as to excite compassion, was a central component in the elicitation of donations, benefactions and legacies.[154] Nor was the practice of showing the poor and unfortunate to potential donators exclusive to Bethlem as similar spectacles of misfortune were performed for public visitors to the Foundling Hospital and Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes.[154] The donations expected of visitors to Bethlem – there never was an official fee[n 16] – probably grew out of the monastic custom of alms giving to the poor.[156] While a substantial proportion of such monies undoubtedly found their way into the hands of staff rather than the hospital poors' box,[n 17] Bethlem profited considerably from such charity, collecting on average between £300 and £350 annually from the 1720s until the curtailment of visiting in 1770.[158] Thereafter the poors' box monies declined to about £20 or £30 per year.[159]

Aside from its fund-raising function, the spectacle of Bethlem also offered moral instruction for visiting strangers.[159] For the "educated" observer Bedlam's theatre of the disturbed might operate as a cautionary tale providing a deterrent example of the dangers of immorality and vice. The mad on display functioned as a moral exemplum of what might happen if the passions and appetites were allowed to dethrone reason.[160] As one mid-eighteenth-century correspondent commented: "[there is no] better lesson [to] be taught us in any part of the globe than in this school of misery. Here we may see the mighty reasoners of the earth, below even the insects that crawl upon it; and from so humbling a sight we may learn to moderate our pride, and to keep those passions within bounds, which if too much indulged, would drive reason from her seat, and level us with the wretches of this unhappy mansion".[161]

Nonetheless, whether "persons of quality" or not, the primary allure of Bethlem for visiting strangers was neither moral edification nor the duty of charity but its entertainment value.[162] In Roy Porter's memorable phrase what drew them "was the frisson of the freakshow",[163] where Bethlem was "a rare Diversion" to cheer and amuse.[164] It became one of a series of destinations on the London tourist trail which included such sights as the Tower, the Zoo, Bartholomew Fair, London Bridge and Whitehall.[165] Curiosity about Bethlem's attractions, its "remarkable characters",[166] including figures such as Nathaniel Lee, the dramatist and Oliver Cromwell's porter, Daniel,[n 18][168] was, at least until the end of the eighteenth-century, quite a respectable motive for visiting.[169]

1791–1900

Despite the palatial pretensions of Bethlem Hospital by the end of the eighteenth century it was suffering evident physical deterioration with uneven floors, buckling walls and a leaking roof.[170] It resembled "a crazy carcass with no wall still vertical – a veritable Hogarthian auto-satire".[171] The financial cost of maintaining the Moorfields building was onerous and the capacity of the Governors to meet these demands was stymied by shortfalls in Bethlem's income in the 1780s occasioned by the bankruptcy of its treasurer; further monetary strains were imposed in the following decade by inflationary wage and provision costs in the context of the Revolutionary wars with France.[172] In 1791, Bethlem's Surveyor, Henry Holland, presented a report to the Governors detailing an extensive list of the building's deficiencies including structural defects and uncleanliness and estimated that repairs would take five years to complete at a cost £8,660. Only a fraction of this sum was allocated and by the end of the decade it was clear that the problem had been largely unaddressed.[173] Holland's successor to the post of Surveyor, James Lewis, was charged in 1799 with compiling a new report on the building's condition. Presenting his findings to the Governors the following year, Lewis declared the building "incurable" and opined that further investment in anything other than essential repairs would be financially imprudent. He was, however, careful to insulate the Governors from any criticism concerning Bethlem's physical dilapidation as, rather than decrying either Hooke's design or the structural impact of the building's subsequent additions, he instead castigated the slipshod nature of its rapid construction. Lewis observed that Bethlem had been partly built over an area of land called "the Town Ditch" – a common receptacle for the precinct's rubbish – and this surface provided little support for a building whose span extended to over 500 feet (150 m).[174] He also noted that the brickwork was not set on any foundation but merely laid "on the surface of the soil, a few inches below the present floor", while the walls, overburdened by the weight of the roofs, were "neither sound, upright nor level".[175]

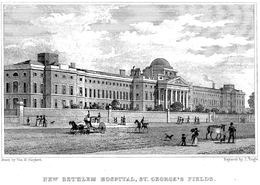

Bethlem rebuilt at St George's Fields

While the logic of Lewis's report was clear, the Court of Governors, facing continuing financial difficulties, only resolved in 1803 behind the project of erecting a new Bethlem at a new site. A fund-raising drive for this purpose was initiated in 1804.[176] In the interim, attempts were made to rehouse patients at local hospitals and admissions to Bethlem, sections of which were deemed uninhabitable, were significantly curtailed such that the patient population fell from 266 in 1800 to 119 in 1814.[177] Financial obstacles to the proposed move remained significant. A national press campaign to solicit donations from the public was launched in 1805. Parliament was successfully lobbied to provide £10,000 for the fund under an agreement whereby the Bethlem Governors would provide permanent accommodation for any lunatic soldiers or sailors of the French Wars.[178] Early interest in relocating the hospital to a site at Gossey Fields had to be abandoned due to financial constraints and stipulations in the original lease agreement for Moorfields which precluded its resale. Instead, the Governors engaged in protracted negotiations with the City to swap the Moorfields site for another municipal owned location at St. George's Fields in Southwark, south of the river Thames. The land transaction was finally concluded in 1810 and provided the Governors with a 12 acres (4.9 ha; 0.019 sq mi) site for the new hospital in what was a swamp-like, impoverished, highly populated, and industrialised region of London.[179]

A competition was held to design the new hospital at Southwark in which the noted Bethlem patient, James Tilly Matthews, was an unsuccessful entrant.[180] The Governors ultimately elected to give James Lewis the task instead.[181] Incorporating the best elements from the three winning competition designs, he produced a building in the neoclassical style that, while drawing heavily on Hooke's original plan, eschewed the ornament of its predecessor.[181] Completed after three years in 1815, it had been constructed during the first wave of county asylum building in England under the provisions of the County Asylum Act ("Wynn's Act") of 1808.[182] Extending to 580 feet (180 m) in length, the new hospital, which ran alongside the Lambeth Road, consisted of a central block with two wings of three storeys on either side.[181] Female patients occupied the west wing and males the east; as at Moorfields, the cells were located off galleries that traversed each wing.[181] Each gallery contained only one toilet, a sink and cold baths. Incontinent patients were kept on beds of straw in cells in the basement gallery; this space also contained rooms, equipped with fireplaces, for attendants. A wing for the criminally insane – a legal category newly minted in the wake of the trial of a delusional James Hadfield for attempted regicide[183] – was completed in 1816.[181] This addition, which housed forty-five men and fifteen women, was wholly financed by the state.[184]

The first 122 patients of the Southwark hospital arrived in August 1815 having been transported across London to their new residence by a convoy of Hackney coaches.[185] Problems with the building were soon noted as the installed steam heating system did not function properly, the basement galleries were damp and the windows of the upper storeys were unglazed "so that the sleeping cells were either exposed to the full blast of cold air or were completely darkened".[186] Although glass was placed in the windows in 1816, the Governors initially supported their decision to leave them unglazed on the basis that it provided ventilation and so prevented the build-up of "the disagreable effluvias peculiar to all madhouses".[187] Faced with increased admissions and overcrowding, new buildings, designed by the architect Sydney Smirke, were added from the 1830s. The wing for criminal lunatics was increased to accommodate a further thirty men while additions to the east and west wings, extending the buildings facade, provided space for an additional 166 inmates and a dome, providing a much-needed touch of grandeur, was added to the hospital chapel.[188] At the end of this period of expansion Bethlem had a capacity for 364 patients.[189]

1815–16 Parliamentary Inquiry

The late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries are typically seen as decisive in the emergence of new attitudes towards the management and treatment of the insane.[190] Increasingly, the emphasis shifted from the external control of the mad through physical restraint and coercion to their moral management whereby self-discipline and control would be inculcated through a system of reward and punishment.[191] For proponents of lunacy reform, the Quaker-run York Retreat, founded in 1796, functioned as an exemplar of this new approach that would seek to re-socialise and re-educate the mad.[191] Bethlem, however, embroiled in scandal from 1814 over the conditions endured by its inmates, would come to symbolise its antithesis.[192]

Bethlem's projected role as a representative institution of all that was awry in the care of the insane was set-in-train by the actions of Edward Wakefield, a Quaker land agent and leading advocate of lunacy reform. In 1812, Wakefield had determined to establish a new London asylum to be modelled on the Retreat and formed a committee to this end. As part of the planning process for this scheme, the committee first resolved to survey the existing metropolitan institutions for the care of the insane: St Luke's, Guy's Hospital and Bethlem.[193] The initial attempts by Wakefield and colleagues to gain access to Bethlem were rebuffed by the hospital authorities who were particularly keen to protect Bethlem's image at at time when they were applying to parliament for funds to finance the move to Southwark.[194] Wakefield, mindful of the difficulties reformers had had in accessing other institutions, persisted and, having secured an invitation to visit from one of Bethlem's Governors, began the first of his many visits to the hospital on 25 April 1815.[194] The conditions which he found there, combined with earlier revelations about patient maltreatment at the York Asylum,[n 19] helped to prompt a renewed campaign for national lunacy reform and the establishment of a 1815 House of Commons Select Committee on Madhouses which examined the conditions under which the insane were confined in county asylums, private madhouses, charitable asylums and in the lunatic wards of Poor-Law workhouses.[195] Wakefield's visits were to the old Bethlem Hospital at the Moorfields site, which was then in a state of disrepair; much of it was uninhabitable and the patient population had been significantly reduced.[196] Contrary to the tenets of moral treatment, patients were not classified in a logical manner and, for Wakefield, their conditions were near bestial:

One of the side rooms contained about ten [female] patients, each chained by one arm to the wall; the chain allowing them merely to stand up by the bench or form fixed to the wall, or sit down on it. The nakedness of each patient was covered by a blanket only ... Many other unfortunate women were locked up in their cells, naked and chained on straw ... In the men's wing, in the side room, six patients were chained close to the wall by the right arm as well as by the right leg ... Their nakedness and their mode of confinement gave the room the complete appearance of a dog kennel.—Edward Wakefield, 1814[197]

Wakefield's investigative party focused on one patient in particular, James Norris, an American marine who had been detained in Bethlem since 1 February 1800. What set Norris apart were the incredible means by which he was restrained:

... a stout iron ring was riveted about his neck, from which a short chain passed to a ring made to slide upwards and downwards on an upright massive iron bar, more than six feet high, inserted into the wall. Round his body a strong iron bar about two inches wide was riveted; on each side of the bar was a circular projection, which being fashioned to and enclosing each of his arms, pinioned them close to his sides. This waist bar was secured by two similar iron bars which, passing over his shoulders, were riveted to the waist both before and behind. The iron ring about his neck was connected to the bars on his shoulders by a double link. From each of these bars another short chain passed to the ring on the upright bar ... He had remained thus encaged and chained more than twelve years.—Edward Wakefield, 1815[198]

In June 1816 Thomas Monro, Principal Physician resigned as a result of scandal when he was accused of ‘wanting in humanity’ towards his patients.[199]

1900 to the present

In 1930, the hospital was moved to an outer suburb of London, on the site of Monks Orchard House between Eden Park, Beckenham, West Wickham and Shirley. The old hospital and its grounds were bought by Lord Rothermere and presented to the London County Council for use as a park; the central part of the building was retained and became home to the Imperial War Museum in 1936.

750th year anniversary and "Reclaim Bedlam" campaign

In 1997 the Bethlem hospital started planning celebrations of its history on the occasion of its 750th anniversary. The service user perspective was not to be included, however, and members of the Psychiatric survivors movement saw nothing to celebrate in either the original Bedlam or in the current practices of mental health professionals towards those in need of care. A campaign called "Reclaim Bedlam" was launched by Pete Shaugnessey, which was supported by hundreds of patients and ex-patients and widely reported in the media. A sit-in was held outside the earlier Bedlam site at the Imperial War Museum. The historian Roy Porter called the Bethlem Hospital "a symbol for man's inhumanity to man, for callousness and cruelty."[200]

Until the 1990s, the hospital and its grounds were in the London Borough of Croydon, but were swapped with the London Borough of Bromley for South Norwood Country Park. This has meant that the hospital is now located in a community which it does not primarily serve (although as many of its services meet the needs of people from across England and Wales and even Gibraltar, to judge its location by its ability to serve a local population conveniently may not be entirely appropriate).

Recent Developments

In 1999, Bethlem Royal Hospital became part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust ("SLaM"), along with the Maudsley Hospital in Camberwell.[citation needed]

In 2001 SLaM sought planning permission for an expanded Medium Secure Unit in 2001 and extensive further works to improve security, much of which would be on Metropolitan Open Land. Local residents groups organised mass meetings to oppose the application, with accusations that it was unfair most patients could be from inner London areas and therefore not locals and that drug use was rife in and around the Hospital. Bromley Council eventually refused the application, with Croydon Council also objecting. However the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister overturned the decision to refuse in 2003, and development started.[citation needed]

The new 89-bed, £33.5m unit (River House) opened in February 2008.[201] It is the most significant development on the site since the hospital was formally opened at Monks Orchard in 1930.[201] River House represents a major improvement in the quality of local NHS care for people with mental health problems.[citation needed]. The unit provides care for people who were previously being treated in hospitals as far as 200 miles away from their families because of the historic shortage of medium secure beds in South-east London. This, in turn, was intended to help the NHS to manage people's progress through care and treatment more effectively.

The Hospital Trust still owns land throughout England, often left to it as a bequest. It owns a lease in Piccadilly for which it has paid the same peppercorn rent for over 200 years. This property is let out to shops and a hotel, which contributes to funding.

Current services

The hospital includes a range of specialist services such as the National Psychosis Unit.[202]

Other services on the hospital include the Bethlem Adolescent Unit which provides care and treatment for young people aged 12 – 18 from across the UK.[203]

The hospital also has an occupational therapy department, which has its own art gallery displaying work of current patients, and a number of noted artists have been past patients at the hospital over the years. Several examples of their work can be found in the Bethlem museum.[204]

Museum and archives

Since 1970, there has been a small museum at Bethlem Royal Hospital. It is open to the public on weekdays. The museum is mainly used to display items from the hospital's art collection, which specialises in work by artists who have suffered from mental health problems, such as former Bethlem patients William Kurelek, Richard Dadd and Louis Wain.Other exhibits include a pair of statues by Caius Gabriel Cibber known as Raving and Melancholy Madness, from the gates of the 17th century Bethlem Hospital, 18th and 19th century furniture, and documents from the archives. Due to the size of the museum only a small fraction of the collections can be displayed at one time, and the exhibits are rotated periodically.

Bethlem Royal Hospital possesses extensive archives from Bethlem Hospital, the Maudsley Hospital and Warlingham Park Hospital, and some of the archives of Bridewell Hospital. There are documents dating back to the 16th century, as well as full modern patient records. The archives are open for inspection by appointment, subject to the laws of confidentiality governing recent patient records.

The Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives and Museum is governed by a registered charity called the Bethlem Art and History Collections Trust. The museum is a member of the London Museums of Health & Medicine.[205]

Notable patients

- Dadd, Richard, artist.[206]

- Frith, John, would-be assailant of King George III.[207]

- Frith, Mary (Moll Cutpurse), also known as Mary Frith or "The Roaring Girl", released from Bedlam in 1644 according to Bridewell records.[208]

- M'Naghten, Daniel, catalyst for the creation of the M'Naghten Rules (criteria for the defence of insanity in the British legal system) after the shooting of Edward Drummond.[209]

- Martin, Jonathan, the man who set fire to York Minster[210]

- Nicholson, Margaret, would-be assassin of King George III.[211]

- Truelock, Bannister, conspirator who plotted to assassinate George III.

- Oxford, Edward, tried for high treason after the attempted assassination of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.[212]

- Pugin, Augustus Welby Northmore (1812–1852) English architect, best known for his work on the Houses of Parliament as well as many churches; in the last year of his life he suffered a breakdown, possibly due to hyperthyroidism, and was for a short period confined in Bethlem.[213]

- Snell, Hannah (1723–1792), sexual impostor and soldier. She spent the last six months of her life in Bethlem.[214]

- Wain, Louis, artist.[215]

See also

- Abraham-men

- History of psychiatric institutions

- John Cutting (psychiatrist)

- Tom o' Bedlam, an anonymous poem c. 1600, about a Bedlamite.

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Although accepted by many historians, including Roy Porter,[61] as Jonathan Andrews points out, Crooke's claim that he was physician to the king, made in the first three editions of his popular medical textbook of human anatomy, Microcosmographia (1615, 1616 and 1618), was baseless.[62]

- ^ Crooke claimed that his keepership of Bethlem had cost him £1,000. Following his dismissal, the additional financial burden imposed by the royal inquiry's lengthy legal process led him to sell his College of Physicians fellowship, attained in 1620, back to that corporate body for a grand total of £5. In 1642 he was still futilely campaigning for his reinstatement. However, he died in relative obscurity in 1648.[60] He was immortalised on stage in the character of the grasping asylum doctor, Alibius, in the Jacobean tragedy, The Changeling (1622).[68]

- ^ The first evidence for the existence of a steward in Bethlem is during Crooke's tenure as keeper-physician.[69]

- ^ a b A toilet.

- ^ Medical knowledge, particularly in the field of anatomical pathology, had made significant advances throughout the eighteenth century but medical treatment remained largely moribund.[92] Despite a declining intellectual foundation,[93] the humoural-based medical practices of depletion and purgation, later recoined as antiphlogistic (anti-inflammatory) therapy, had undergone little change since the time of Galen in the second century AD.[94] Under this traditional conception, challenged increasingly from the seventeenth century,[93] physical and mental health was dependent upon the maintenance of a proper balance between the four bodily humours of blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile (choler). The humours were replenished through the ingestion of food and discharged naturally when they became noxious.[95] Disease could arise, however, when there was an overabundance or plethora in a given humour and this necessitated its removal from the body through venesection, purging, or through a reduction of dietary intake.[94]

- ^ For instance Thomas Allen, Bethlem physician from 1667 until his death in 1684, happily dismissed the expressed wish of his colleagues in the Royal Society that he should try the then experimental treatment for insanity of animal-to-human blood transfusion "upon some mad person in ... Bethlem".[96]

- ^ The total cost of the new Bethlem built at Moorfields came to £17,000.[108]. This expense served to underline the philanthropic magnificence of the presiding governors and rendered Bethlem's patients, in Edward Hatton's words: "great Objects of Charity; for this new Structure cost erecting about [£]17000 whereby not only the Stock of the Hospital is expended, but the Governours are out of Pockets several Sums which they were obliged to take up for that purpose ..."[109]

- ^ Estimates of the scale of the building run from 528 to 540 feet (161 to 160 m) wide and 30 to 40 feet (9.1 to 12 m) deep.[111]

- ^ A double-pile building has two rooms arranged longitudinally along a central corridor. A single-pile has only one.[108]

- ^ The Governors debated whether to install iron grates at the entrance to the galleries which would have allowed patients the freedom to walk in them while preventing intercourse between male and female patients. This proposal was resisted, however, by those who thought it would have spoiled the view offered by the galleries. However, iron grates with a door to allow visitors to pass through them were eventually installed in 1869 and presumably it is from this date patients who were not otherwise violent were permitted to walk the galleries. Patients if deemed well enough could, of course, use the rear yards for exercise both before and after this date.[117] This allowed them to "take the aire in order to [aid] their Recovery".[118]

- ^ In 1676 there were 34 cells on one side of each of the four galleries, or 136 cells in all. The cells, large and well ventilated for the time by any measure, were 12 feet (3.7 m) deep by 8 feet 10 inches (2.69 m) wide and 12 feet 10 inches (3.91 m) high.[124]

- ^ The image shows a shaven-head and near-naked Rakewell in one of galleries of Bethlem, reclining in a position reminiscent of one of Cibber's figures. An attendant (barely visible in this painted version) is in the process of manacling his leg. The figure standing over Rakewell wearing a wig and with his head bowed forward is likely a physician and may have just bled the patient.Scull and Andrews opine that this figure "bears more than a passing resemblance to" James Monro, the father of John Monro.[128]

- ^ This position, argued by Andrews et al., principally relies on a reading of the last line of the report of the 1598 visitation, quoted above, which refers to the fact that Bethlem was then "so loathsomely and filthely, kept not fitt for any man to come into". While conceding that "come into" here may refer to admissions they thought this unlikely given that the Bridewell Governors in the same line had already disparaged the hospital's patient accommodation. Instead, they argue, a more plausible interpretation is that it evinces the concern of the Governors that the hospital conditions might dissuade public visitors which they were anxious to increase as a means of augmenting Bethlem's revenues.[130]

- ^ While in London, the young Percy and his troupe also "saw the lions, the shew of Bethlem, the places where the prince was created and the fireworks at the Artillery Garden".[134] Carol Neely, however, thinks it improbable that an eight year old Lord Percy and his equally young cousins, while his father, Henry Percy, was then ensconced in the Tower of London, would have visited Bethlem at this date, particularly in consideration of the ramshackle condition of the hospital in the early seventeenth-century.[135] This is to ignore, however, the fact that there are many references to children visiting Bethlem.[136]

- ^ It is still frequently and erroneously asserted that either during the eighteenth-century or as late as 1814 or 1815, the periodisation depending on the source, there were 96,000 such visits to Bethlem in a given year.[143] For example, Michel Foucault in his History of Madness (2006) claimed : "As late as 1815, if a report presented to the House of Commons is to believed, Bethlem Hospital showed its lunatics every Sunday for one penny. The annual revenue from those visits amounted to almost 400 pounds which means that an astonishing 96,000 visitors came to see the mad each year."[144] As Andrews et al. have noted, none of the claims in the above paragraph have any basis in fact.[31] The notional figure of 96,000 visitors to Bethlem, which was first applied to the eighteenth-century, ultimately derives from the original archival research of O'Donoghue and his 1914 history of the hospital.[145] From this source Robert R. Reed arrived at the above dubious calculation of visitations per annum by dividing the contents of the Bethlem poors' box for a single year by the supposed entrance fee per person. However, there is no credible evidence to suggest that there was an official entrance charge of one penny, there is no way of knowing how much individual visitors donated and the figure of £400 includes the entirety of the contents of the poors' box and hence all the charitable donations that Bethlem received.[146] It is likely that Foucault's source for the figure is Reed and he transposes it to the nineteenth-century.[147] Unsurprisingly, the report of the parliamentary inquiry of 1815–16 does not support any of his claims.[148] The impossibility of his account is underlined by the fact that Sunday visits were banned in 1657 and public visitations to Bethlem were curtailed from 1770.[149]

- ^ However, during the seventeenth- and eighteenth-centuries staff at the asylum did try to exact such a fee and by 1742 it was customary for the porter to demand a minimum of one penny from visiting strangers.[155]

- ^ The servants of Bethlem were allowed their own poors' box from 1662. The diversion of other monies into the pockets of the hospital staff undoubtedly helped to keep wages down. [157]

- ^ Daniel was purportedly 7 feet 6 inches (2.29 m) tall and the model for Cibber's figure of "Raving madness".[167]

- ^ Not to be confused with the York Retreat.

Footnotes

- ^ Tuke 1882, p. 60.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 15, 23; Vincent 1998, p. 213.

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, pp. 144–45; Vincent 1998, p. 224; Porter 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 25

- ^ a b Vincent 1998, p. 224

- ^ Vincent 1998, p. 217

- ^ Vincent 1998, p. 226

- ^ Vincent 1998, pp. 230–31.

- ^ a b Vincent 1998, pp. 231.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 84

- ^ Vincent 1998, p. 231; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 57

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 56

- ^ Phillpotts 2012, p. 200

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 16, 58; Phillpotts 2012, p. 207.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 55

- ^ Phillpotts 2012, p. 207; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 81

- ^ a b Vincent 1998, p. 232

- ^ Jones 1955, p. 11

- ^ Andrews 1995, p. 11

- ^ Andrews 1995, p. 11; Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 17, 60

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 148

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 149; Porter 2006, pp. 156–57

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 1; Allderidge 1979a, p. 149.

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 144.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 1

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 1–2

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 142; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 81; Vincent 1998, p. 227

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 142

- ^ Porter 2006, p. 156; Whittaker 1947, p. 742.

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, pp. 142–43

- ^ a b Andrews et al. 1997, p. 3

- ^ O'Donoghue 1914

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 115–16

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 143; Allderidge 1979b, p. 323.

- ^ Porter 1997, p. 41

- ^ Scull 1999, p. 249

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 113–15

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 82

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 131

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 1–2, 130–31

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 130; Hattori 1995, p. 283

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 130

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 132; Hattori 1995, p. 287

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 132; Jackson 2000, p. 224

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 245

- ^ a b c Andrews et al. 1997, p. 261

- ^ a b Allderidge 1979a, p. 149

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 91–92

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 91

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 153

- ^ a b Jackson 2005, p. 49

- ^ Quoted in Jackson 2000, p. 223

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 153; Neely 2004, p. 171.

- ^ "A View of Bethalem", 4 December 1598, quoted in Allderidge 1979a, p. 153

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 124

- ^ Allderidge 1979b, p. 323

- ^ Jackson 2005, p. 49; Jackson 2000, p. 223; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 123

- ^ Allderidge 1979a, p. 154

- ^ a b Allderidge 1985, p. 29

- ^ a b Birken 2004

- ^ a b Porter 1997, p. 42

- ^ a b Andrews 1991, p. 246

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 63, 261

- ^ Porter 1997, p. 42; Andrews 1991, p. 246

- ^ a b Andrews 1991, p. 181

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 247, n. 15

- ^ Porter 1997, p. 42; Andrews 1991, p. 245.

- ^ Birken 2004; Neely 2004, p. 199.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 88

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 261; Andrews 1991, pp. 242, 322.

- ^ a b Allderidge 1979a, p. 145

- ^ a b c d Andrews et al. 1997, p. 51

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 222

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 155

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 155–56

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 157–58

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 157

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 181, 183

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 187

- ^ Andrews 1991, pp. 183–86

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 4

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 4; Whittaker 1947, p. 747

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 262

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 262–63

- ^ Andrews 1991, pp. 257, 260

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 265–66; Andrews 1991, p. 244.

- ^ Parry-Jones 1971.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 269

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 266

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 266–67

- ^ a b c Andrews et al. 1997, p. 267

- ^ Dowling 2006, pp. 22–23

- ^ a b Porter 2006, p. 72

- ^ a b Noll 2007, p. x

- ^ Porter 2006, pp. 57–58

- ^ Quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, p. 271

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 271

- ^ a b Quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, p. 272

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 272

- ^ a b Andrews et al. 1997, p. 274–75

- ^ a b c Andrews et al. 1997, p. 275

- ^ Porter 2006, pp. 165–66

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 277

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 267; Porter 2006, pp. 164–65

- ^ a b c Stevenson 1996, p. 254

- ^ Stevenson 1997, p. 233

- ^ Allderidge 1979b, p. 328; Stevenson 1996, p. 263

- ^ a b c d Stevenson 1996, p. 259

- ^ Edward Hatton, A New View of London: Or, an Ample Account of that City, 2 vols. (London, 1708), 2, p. 732, quoted in Stevenson 1996, p. 260

- ^ Porter 2002, p. 71; Stevenson 1996, p. 258

- ^ Stevenson 1996, pp. 264, 274 n. 88

- ^ a b c Stevenson 1996, p. 260

- ^ Stevenson 1996, p. 260; Gilman 1996, pp. 17–18; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 154

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 234

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 172 n. 170

- ^ Roger L'Strange, Bethlehems Beauty, Londons Charity, and the Cities Glory, A Panegyrical Poem on that Magnificent Structure lately Erected in Moorfields, vulgarly called New Bedlam. Humbly Addressed to the Honorable Master, Governors, and other Noble Benefactors of that most Splendid and useful Hospital (London, 1676), quoted in Andrews 1991, p. 84.

- ^ Stevenson 1996, p. 266

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 173

- ^ Quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, p. 152

- ^ Gibson 2008

- ^ Andrews 1994, p. 64; Stevenson 1996, p. 271 n. 20; Scull 1993, p. 22 n. 59

- ^ Andrews 1994, p. 65; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 150; Allderidge 1979a, p. 31

- ^ Andrews 1994, p. 65

- ^ Stevenson 1996, p. 261

- ^ Stevenson 1996, pp. 262–67; Andrews 1994, pp. 70, 171.

- ^ Stevenson 1996, p. 255

- ^ "Philotheos Physiologus" (Thomas Tyson), A Treatise of Dreams and Visions ... (1689), A Discourse of the Causes Natures and Cure of Phrensie, Madness or Distraction, ed. Michael V. DePorte, Los Angeles: Augustan Reprint Society (1973), pp. 289–91, quoted in Stevenson 1996, p. 270, n. 10

- ^ Andrews & Scull 2003, p. 37

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 11

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 132. See also Jackson 2000, pp. 223–24; Neely 2004, p. 209

- ^ More 1903, p. 7; Hattori 1995, p. 287

- ^ Quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, p. 132

- ^ Jackson 2005, p. 15; Jackson 2000, p. 224; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 132

- ^ Quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, p. 187

- ^ Neely 2004, pp. 202, 209

- ^ Gale 2012.

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 132; Jackson 2000, p. 224.

- ^ Jackson 2000, p. 224; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 130

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 178

- ^ Thomas Tryon, A Treatise of Dreams and Visions, 2nd edition (London: T. Sowle, 1695), p. 290, quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 178, 195 n. 5

- ^ The World, no. xxiii, 7 June 1753, p. 138, quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 178, 195 n. 6

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 14

- ^ Today Programme 2008; MacDonald 1981, p. 122; Foucault 2006, p. 143; Reed 1952, pp. 25–26; Covey 1998, p. 15; Oberhelman 1995, p. 13; Skultans 1979, p. 38, Phillips 2007, p. 89; Kent 2003, p. 51; Kathol & Gatteau 2007, p. 18

- ^ Foucault 2006, p. 143

- ^ O'Donoghue 1914; Allderidge 1985, p. 23

- ^ Allderidge 1985, p. 23; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 180

- ^ Neely 2004, p. 208

- ^ Scull 2007

- ^ Allderidge 1985, p. 23; Scull 1993, p. 51

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 18

- ^ De Saussure 1902, pp. 92–93

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 181

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 19

- ^ a b Andrews et al. 1997, p. 182

- ^ Andrews 1991, pp. 14–15

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 14

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 20, 23

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 16

- ^ a b Andrews 1991, p. 23

- ^ Andrews 1991, pp. 23–4

- ^ Anonymous, The World, no. xxxiii (7 June 1753) p. 138| quoted in Andrews 1991, pp. 23–24

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 186

- ^ Porter 2006, p. 157

- ^ Tyron, Dreams, p. 291 quoted in Andrews 1991, p. 38

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 187; Porter 2006, p. 157

- ^ William Hutton, The Life of William Hutton, pub. by his daughter, Catherine Hutton (London, 1816), 1749, p. 71, quoted in Andrews 1991, p. 40

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 41 n. 154

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 41

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 40

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 397

- ^ Porter 1997, p. 43

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 381

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 398

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 399; Scull, MacKenzie & Hervey 1996, p. 18

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 400

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 400–1

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 401; Scull, MacKenzie & Hervey 1996, p. 19

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 402; Scull & MacKenzie Hervey1996, p. 19

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 403

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 406

- ^ a b c d e Andrews et al. 1997, p. 407

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 407; Smith 1999, p. 6

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 391–92, 404

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, pp. 403–5

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 409

- ^ Quoted in Andrews et al. 1997, p. 409

- ^ Quoted in Darlington 1955, pp. 76–80; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 409

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 409–10

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 410

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 416

- ^ a b Andrews et al. 1997, p. 417

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 415, 416, 417

- ^ Scull 1993, p. 112; Moss 2008; Scull, MacKenzie & Hervey 1996, p. 28; Wakefield 1812, pp. 226–29

- ^ a b Andrews et al. 1997, p. 421

- ^ Scull 1993, p. 112; Andrews et al. 1997, p. 415

- ^ Andrews 1991, p. 422; Scull 1993, p. 113.

- ^ "Extracts from the Report of the Committee Employed to Visit Houses and Hospitals for the Confinement of Insane Persons, With Remarks, by Philanthropus', The Medical and Physicial Journal, 32, August 1814, pp. 122–8, quoted in Scull 1993, p. 113

- ^ Quoted in Andrews & Scull 2001, p. 274 n. 85

- ^ Andrews 2010

- ^ Olden 2003

- ^ a b Cooke 2008

- ^ SLaM 2012a

- ^ SLaM 2012b

- ^ Bethlem Gallery 2012

- ^ Archives and Museum (2012a, 2012b)

- ^ Porter 2006, p. 25

- ^ Poole 2000, p. 95

- ^ Griffiths 2008

- ^ Moran 1985, p. 41

- ^ Harrison 1979, p. 211

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 359

- ^ Poole 2000, p. 286

- ^ Hill 2007, pp. 484–90, 492.

- ^ Wheelwright 2008

- ^ Andrews et al. 1997, p. 657

Sources

Primary sources

- De Saussure, César. A Foreign View of England in the Reigns of George I & II: the Letters of Monsieur César de Saussure to his Family. Edited and translated by Madame Van Muyden. London: John Murray; 1902.

- More, Thomas. The Four Last Things (1522). Edited by D. O'Connor. London: Art and Book Co.; 1903.

- Wakefield, Edward. Plan of an Asylum for Lunatics, & c. The Philanthropist. 1812;2:226–29.

Secondary sources

- Books

- Andrews, Jonathan; Briggs, Asa; Porter, Roy; Tucker, Penny; Waddington, Keir. The History of Bethlem. London & New York: Routledge; 1997. ISBN 0415017734.

- Andrews, Jonathan; Scull, Andrew. Undertaker of the Mind: John Monro and Mad-Doctoring in Eighteenth-Century England. California: California University Press; 2001. ISBN 9780520231511.

- Andrews, Jonathan; Scull, Andrew. Customers and Patrons of the Mad-Trade:The Management of Lunacy in Eighteenth-Century London: With the Complete Text of John Monro's 1766 Case Book. Berkeley & Los Angeles CA: University of California Press; 2003. ISBN 9780520226609.

- Covey, Herbert C.. Social Perceptions of People with Disability in History. Charles C. Thomas; 1998. ISBN 9780398068370.

- Darlington, Ida, ed.. Survey of London: Volume 25. St George's Fields (The Parishes of St George The Martyr, Southwark and St Mary, Newington). London: London County Council; 1955. Chapter 9: Bethlem Hospital, Now the Imperial War Museum, in Lambeth Road.

- Dowling, William C.. Oliver Wendell Holmes in Paris: Medicine, Theology and the Autocrat at the Breakfast Table. Lebanon NH: University of New Hampshire Press; 2006. ISBN 9781584655800.

- Foucault, Michel. History of Madness. Edited by Jean Khalfa. Translated by Jonathan Murphy & Jean Khalfa. London & New York: Routledge; 2006. ISBN 9780415277013.

- Gilman, Sander L.. Seeing the Insane. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1996. ISBN 9780803270640.

- Harrison, John Fletcher Clews. The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism, 1780–1850. London: Taylor and Francis; 1979. ISBN 9780710001917.

- Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. London: Allen Lane; 2007. ISBN 978-0-7139-9499-5.

- Jackson, Kenneth S.. Separate Theaters: Bethlem ("Bedlam") Hospital and the Shakespearian Stage. Newark: University of Delaware; 2005. ISBN 9780874138900.

- Jones, Kathleen. Lunacy, Law and Conscience, 1744–1845. New York & London: Routledge; 1955. (The Sociology of Mental Health). ISBN 9780415178020.

- Kathol, Roger G.; Gatteau, Suzanne. Healing Body and Mind: A Critical Issue for Health Care Reform. Westport CT: Praeger; 2007. ISBN 9780275992019.

- Kent, Deborah. Snake Pits, Talking Cures and Magic Bullets. Brookfield CT: Twenty-First Century Books; 2003. ISBN 9780761327042.

- MacDonald, Michael. Mystical Bedlam: Madness, Anxiety and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1981. ISBN 9780521273824.

- Neely, Carol Thomas. Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture. New York: Cornell University Press; 2004. ISBN 9780801489242.

- Noll, Richard. The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. 3rd ed. New York: Facts on File; 2007. ISBN 9780816075089.

- Oberhelman, David D.. Dickens in Bedlam: Madness and Restraint in his Fiction. York Press; 1995. ISBN 9780919966963.

- O'Donoghue, Edward Geoffrey. The Story of Bethlem from its Foundation in 1247. London: T.F. Unwin; 1914.

- Parry-Jones, William Llywelyn. The Trade in Lunacy: A Study of Private Madhouses in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1971. ISBN 9780802001559.

- Phillips, Bob. Overcoming Anxiety and Depression. Eugene OR: Harvest House Publishers; 2007. ISBN 9780736919968.

- Poole, Steve. The Politics of Regicide in England, 1760–1850: Troublesome Subjects. Manchester: Manchester University Press; 2000. ISBN 9780719050350.