| Dates | circa 3900 BC — circa 3650 BC.[1] |

|---|---|

| Major sites | El-Amra |

| Preceded by | Tasian culture, Badari culture, Merimde culture |

| Followed by | Naqada II (Gerzeh culture) |

The Amratian culture, also called Naqada I, was a culture of prehistoric Upper Egypt. It lasted approximately from 4000 to 3500 BC.[2]

Overview

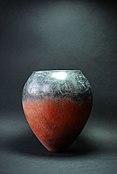

The Amratian culture is named after the archaeological site of el-Amra, located around 120 km (75 mi) south of Badari in Upper Egypt. El-Amra was the first site where this culture group was found without being mingled with the later Gerzeh culture (Naqada II). However, this period is better attested at the Nagada site, thus it also is referred to as the Naqada I culture.[3] Black-topped pottery continued to be produced, but white cross-line pottery, a type which has been decorated with close parallel white lines being crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, begins to be produced during this time. The Amratian falls between S.D. 30 and 39 in Flinders Petrie's sequence dating system.[4][5]

The Amratians possessed slaves, and constructed rowboats of bundled papyrus in which they could sail the Nile.[6] Trade between the Amratian culture bearers in Upper Egypt and populations of Lower Egypt is attested during this time through new excavated objects. A stone vase from the north has been found at el-Amra. The predecessor Badarian culture had also discovered that malachite could be heated into copper beads;[a] the Amratians shaped this metal by chipping.[6] Obsidian and a very small amount of gold were both imported from Nubia during this time.[3][4] Trade with the oases also was likely.[3] Cedar was imported from Byblos, marble from Paros, as well as emery from Naxos.[6]

New innovations such as adobe buildings, for which the Gerzeh culture is well known, also begin to appear during this time, attesting to cultural continuity. However, they did not reach nearly the widespread use that they were known for in later times.[7] Additionally, oval and theriomorphic cosmetic palettes appear to be used in this period. However, the workmanship was still very rudimentary and the relief artwork for which they were later known is not yet present.[8]

Each Amratian village had an animal deity; amulets were worn of humans and various animals including birds and fish. Food, weaponry, statuettes, decorations, malachite, and occasionally dogs were buried with the deceased.[6]

Egyptian disk-shaped macehead 4000–3400 BCE. At the end of the period, it was replaced by the superior Mesopotamian-style pear-shaped macehead, as seen on the Narmer Palette.[9]

Early cosmetic palettes

Siltstone was first utilized for cosmetic palettes by the Badari culture. The first palettes used in the Badarian Period and in Naqada I were usually plain, rhomboidal or rectangular in shape, without any further decoration. It is in the Naqada II period in which the zoomorphic palette is most common.

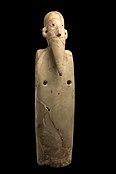

Bearded figurines

Many figurines are known from Naqada I, which were carved on animal tusks. The figurines usually have pointed beards, and some trace of hair.[10] They may represent people dressed in long cloaks.[10] Bearded men also appear in many other pre-dynastic artifacts, such as the Gebel el-Arak Knife.[11] The headgear of the Mesopotamian-style "Lord of Animals" on the Gebel el-Arak knife may also be comparable to the torus-shaped headgear visible on many of the Naqada I figurines.[11]

Figurine of a bearded man by the Naqada I culture, 3800–3500 BC, from Upper Egypt. Musée des Confluences (Lyon, France)

Hippopotamus tusk with carved head of a bearded man with torus-like headgear, Late Naqada I–Early Naqada II, 3800–3400 BCE. Brooklyn Museum.[11]

Other artifacts

Lower-Egypt basalt jars in the shape of pottery from Maadi, Naqada I-II, British Museum EA 34398, EA 26654

Relative chronology

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic Pottery Neolithic | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC 11000 | Europe | Egypt | Syria Levant | Anatolia | Khabur | Sinjar Mountains Assyria | Middle Tigris | Low Mesopotamia | Iran (Khuzistan) | Iran | Indus/ India | China |

| 10000 | Pre-Pottery Neolithic A Gesher[13] Mureybet (10,500 BC) | Early Pottery (18,000 BC)[14] | ||||||||||

| 9000 | Jericho Tell Abu Hureyra [15] | |||||||||||

| 8000 | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Jericho Tell Aswad | Göbekli Tepe Çayönü Aşıklı Höyük | Initial Neolithic (Pottery) Nanzhuangtou (8500–8000 BC) | |||||||||

| 7000 | Egyptian Neolithic Nabta Playa (7500 BC) | Çatalhöyük (7500–5500) Hacilar (7000 BC) | Tell Sabi Abyad Bouqras | Jarmo | Ganj Dareh Chia Jani Ali Kosh | Mehrgarh I[13] | ||||||

| 6500 | Neolithic Europe Franchthi Sesklo [16] | Pre-Pottery Neolithic C ('Ain Ghazal) | Pottery Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad Bouqras | Pottery Neolithic Jarmo | Chogha Bonut | Teppe Zagheh | Pottery Neolithic Peiligang (7000–5000 BC) | |||||

| 6000 | Pottery Neolithic Sesklo Dimini | Pottery Neolithic Yarmukian (Sha'ar HaGolan) | Pottery Neolithic Ubaid 0 (Tell el-'Oueili) | Pottery Neolithic Chogha Mish | Pottery Neolithic Sang-i Chakmak | Pottery Neolithic Lahuradewa Mehrgarh II Mehrgarh III | ||||||

| 5600 | Faiyum A | Amuq A | Halaf Halaf-Ubaid | Umm Dabaghiya | Samarra (6000–4800 BC) | Tepe Muhammad Djafar | Tepe Sialk | |||||

| 5200 | Linear Pottery culture (5500–4500 BC) | Amuq B | Hacilar Mersin 24–22 | Hassuna | Ubaid 1 (Eridu 19–15) Ubaid 2 (Hadji Muhammed) (Eridu 14–12) | Susiana A | Yarim Tepe Hajji Firuz Tepe | |||||

| 4800 | Pottery Neolithic Merimde [17] | Amuq C | Hacilar Mersin 22–20 | Hassuna Late Gawra 20 | Tepe Sabz | Kul Tepe Jolfa | ||||||

| 4500 | Amuq D | Gian Hasan Mersin 19–17 | Ubaid 3 | Ubaid 3 (Gawra) 19–18 | Ubaid 3 | Khazineh Susiana B | ||||||

3800 | Badarian Naqada | Ubaid 4 | ||||||||||

| Succeeded by: Historical Ancient Near East | ||||||||||||

See also

- 5.9 kiloyear event

- Prehistoric Egypt

- Naqada culture

References

Footnotes

- ^ Copper may have also been imported from the Sinai Peninsula or perhaps Nubia.

Citations

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan. "The relative chronology of the Naqada culture: Problems and possibilities [in:] Spencer, A.J. (ed.), Aspects of Early Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1996: 36-69": 64.

- ^ Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ a b c Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Blackwell. p. 28. ISBN 0-631-17472-9.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Alan (1964). Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: University Press. p. 390.

- ^ Newell, G.D. (2012). The relative chronology of PNC I. A new chronological synthesis for the Egyptian Predynastic. ex.cathedra Press.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Homer W. (2015) [1952]. Man and His Gods. Lulu Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9781329584952.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-691-03606-3.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan (1964). Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: University Press. p. 393.

- ^ Isler, Martin (2001). Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building the Egyptian Pyramids. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3.

- ^ a b Hendrickx, Stan; Adams, Barbara; Friedman, R. F. (2004). Egypt at Its Origins: Studies in Memory of Barbara Adams : Proceedings of the International Conference "Origin of the State, Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt," Krakow, 28 August - 1st September 2002. Peeters Publishers. p. 892. ISBN 978-90-429-1469-8.

- ^ a b c Hendrickx, Stan; Adams, Barbara; Friedman, R. F. (2004). Egypt at Its Origins: Studies in Memory of Barbara Adams : Proceedings of the International Conference "Origin of the State, Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt," Krakow, 28 August - 1st September 2002. Peeters Publishers. p. 894. ISBN 978-90-429-1469-8.

- ^ Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- ^ a b Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- ^ Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- ^ Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- ^ Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- ^ Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.

_(3802228234).jpg)

._Predynastic%2c_Naqada_I._4000-3600_BC._EA_37913_(British_Museum).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)