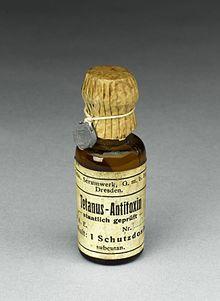

A vintage single-dose bottle of tetanus antitoxin manufactured by Sächsisches Serumwerk Dresden (now GlaxoSmithKline) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | HyperTET S/D, others |

| Other names | tetanus immune globulin, tetanus antitoxin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Routes of administration | IM |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

Anti-tetanus immunoglobulin, also known as tetanus immune globulin (TIG) and tetanus antitoxin, is a medication made up of antibodies against the tetanus toxin.[1] It is used to prevent tetanus in those who have a wound that is at high risk and have not been fully vaccinated with tetanus toxoid.[1] It is also used to treat tetanus along with antibiotics and muscle relaxants.[1] It is given by injection into a muscle.[1]

Common side effects include pain at the site of injection and fever.[1] Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis may rarely occur.[1] There is also a very low risk of the spread of infections such as viral hepatitis and HIV/AIDS with the human version.[1] Use during pregnancy is deemed acceptable.[2] It is made from either human or horse blood plasma.[1][3]

Use of the horse version became common in the 1910s, while the human version came into frequent use in the 1960s.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[5] The human version may be unavailable in the developing world.[3] The horse version is not typically used in the developed world due to the risk of serum sickness.[6]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Tetanus Immune Globulin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Tetanus immune globulin Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b International Encyclopedia of Public Health (2 ed.). Academic Press. 2016. p. 161. ISBN 9780128037089. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09.

- ^ Plotkin, Stanley A.; Orenstein, Walter A.; Offit, Paul A. (2012). Vaccines. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 103, 757. ISBN 978-1455700905. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Fauci, Anthony S.; Braunwald, Eugene; Kasper, Dennis L.; Hauser, Stephen; Longo, Dan; Jameson, J. Larry; Loscalzo, Joseph (2008). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 17th Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 773. ISBN 9780071641142. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09.