| M62 coach bombing | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Troubles | |

Aftermath of the M62 coach bombing | |

| Location | Between junctions 26 and 27 of the M62 motorway, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°44′36″N 1°40′07″W / 53.74333°N 1.66861°W |

| Date | 4 February 1974 c. 00:15[1] |

Attack type | Time bomb |

| Deaths | 12 (9 soldiers, 3 civilians)[2] |

| Injured | 38 (soldiers and civilians) |

| Perpetrator | Provisional IRA |

The M62 coach bombing, sometimes referred to as the M62 Massacre,[3] occurred on 4 February 1974 on the M62 motorway in northern England, when a 25-pound (11 kg)[n 1] Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) bomb hidden inside the luggage locker of a coach carrying off-duty British Armed Forces personnel and their family members exploded, killing twelve people (nine soldiers and three civilians) and injuring thirty-eight others aboard the vehicle.[5][6]

Ten days after the bombing, 25-year-old Judith Ward was arrested in Liverpool while waiting to board a ferry to Ireland.[7] She was later convicted of the M62 coach bombing and two other separate, non-fatal attacks and remained incarcerated until her conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal in 1992, with the court hearing Government forensic scientists had deliberately withheld information from her defence counsel at her October 1974 trial which strongly indicated her innocence.[8] As such, her conviction was declared unsafe.[9]

Ward was released from prison in May 1992, having served over 17 years of a sentence of life imprisonment plus thirty years.[10] Her conviction is seen as one of the worst miscarriages of justice in British legal history.[11][12]

The M62 coach bomb has been described as "one of the IRA's worst mainland terror attacks" and remains one of the deadliest mainland acts of the Troubles.[13]

The bombing

The bombed coach had been specially commissioned to carry British Army and Royal Air Force personnel—on weekend leave with their families—to and from bases at Catterick and Darlington during a period of railway strike action.[14][15] The vehicle itself had departed from Manchester in the late evening of Sunday 3 February and was travelling at approximately 60 mph (100 km/h) along the M62 motorway en route to Catterick Garrison.[16] Shortly after midnight, as most of those aboard were sleeping and when the bus was travelling between junctions 26 and 27 of the M62, the bomb—concealed within a suitcase or similar parcel inside the coach's luggage compartment—exploded.[17][n 2]

The explosion reduced the rear of the coach to a "tangle of twisted metal", trapping several casualties within the debris[19] and throwing individuals and severed limbs up to 250 yards (230 m) upon and around the motorway.[20] No other vehicle was damaged in the explosion, although the vehicle travelling immediately behind the coach is known to have ploughed into the scattered debris of the rear of the coach.[21] The coach itself travelled for more than 200 yards (180 m) before the driver, 39-year-old Roland Handley (himself injured by flying glass), was able to steer the coach to a halt upon the hard shoulder.[22][n 3]

Immediate efforts

One surviving soldier later described his recollections of having been blown through the emergency doors of the coach, only to find himself lying upon the ground viewing a "mangled wreck". This soldier later assisted a young girl aged approximately 17 with injured legs whom he found lying on her back approximately 200 yards (180 m) "back up the [motorway]". According to this individual, the girl had repeatedly hysterically screamed: "My God! The floor just opened up and I fell through!" as he provided medical assistance.[24] Another survivor, nine-year-old David Dendeck, regained consciousness to find himself trapped in the wreckage of the coach listening to his 14-year-old sister, Catherine, shouting his name as he observed other survivors "screaming and running up the verge" alongside the coach.[25]

One of the first motorists to offer assistance after Handley had navigated the coach to a halt was John Clark, who later recollected seeing a young man lying upon the motorway with one leg partially severed and the body of a child, stating: "It was just absolutely ... unbelievable. It was dark, so you couldn't see how bad the injuries really were, but it was the smell of it. It was absolutely total carnage."[25]

The entrance hall of the nearby westbound section of the Hartshead Moor service station was used as an impromptu first aid station for those wounded in the blast.[26] Off-duty staff at Bradford Royal Infirmary and Batley General Hospital were also contacted and encouraged to report for duty in response to the emergency.[18]

Fatalities

The explosion killed eleven people outright and wounded over thirty others,[27] one of whom died four days later. Amongst the dead were nine soldiers – two from the Royal Artillery, three from the Royal Corps of Signals and four from the 2nd Battalion Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. Four of the servicemen killed in the bombing were teenagers and all but one of the serving personnel killed in the explosion hailed from Greater Manchester.[n 4] Numerous others upon the coach suffered severe injuries, including a six-year-old boy, who was badly burned.[20]

One member of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers killed in the explosion was 23-year-old Corporal Clifford Haughton, whose entire family, consisting of his wife, Linda (also 23), and sons Lee, aged 5, and Robert, aged 2, were also killed. All four had been sitting directly above the bomb, and all were killed instantly.[29][n 5]

Reaction

Although mainland Britain had seen several IRA attacks—successful or otherwise—within the previous year, the M62 coach bombing was the most severe attack upon the mainland to date.[31] Press and public alike were incensed, with the BBC describing the bombing as "one of the IRA's worst mainland terror attacks"[32] and national newspapers such as The Guardian describing the atrocity as an "IRA outrage on the British mainland".[33] The Irish newspaper The Sunday Business Post later described the bombing as "the worst" of the "awful atrocities perpetrated by the IRA" during this period.[34]

Politicians from all three major parties called for "swift justice" against the perpetrator or perpetrators and the IRA in general.[35] Within twenty-four hours of the explosion, demands had been heard in the Parliament of the United Kingdom that Irish citizens entering Britain carry identification and passports at all times. The Secretary of State for Defence, Ian Gilmour, confirmed on 5 February these existing laws were to be reviewed.[36]

IRA Army Council response

Although a police spokesman initially emphasised that investigators were keeping an "open mind" as to the cause of the explosion, in the days immediately following the bombing, suspicion quickly fell upon the Provisional IRA,[37] which had extended its campaign to England the previous year.[38]

In an interview shortly after the bombing, IRA Army Council member Dáithí Ó Conaill was challenged over the choice of target, the lack of the official IRA protocol of an advance warning, and the deaths of civilians, including children. Ó Conaill replied that the coach was selected as a legitimate target because IRA intelligence had indicated that the vehicle was commissioned to carry military personnel only.[39]

Investigation

Arrest of Judith Ward

At 6:30 a.m. on 14 February, police encountered a 25-year-old mentally ill English woman named Judith Teresa Ward[40] standing in a shop doorway in Liverpool, seeking shelter from the cold and rain. As her driving licence had been issued in Northern Ireland, Ward was detained for questioning. The following day, Ward was transferred to the custody of West Yorkshire Police to be questioned further with regards to the M62 coach bombing.[41]

The ensuing police investigation was led by Detective Chief Superintendent George Oldfield. This investigation would prove to be rushed, careless and ultimately forged, but culminated in Ward claiming culpability for the bombing. According to Ward, she had planted the bomb in the luggage compartment of the coach while the vehicle was parked at Manchester Piccadilly Gardens bus station. The luggage compartment had already been open when she, "shaking like a leaf", placed the bag containing the bomb between "a few army issue bags" in the luggage compartment. She had then turned and "legged it" out of the station.[42]

Griess tests conducted by forensic scientist Frank Skuse upon Ward's fingernails revealed what he described as "faint traces" of nitrites upon one of her nails. A subsequent examination of Ward's caravan by Dr Skuse also revealed what he concluded to be traces of an explosive substance upon a duffel bag.[43]

Suspect background

Ward had been born in Stockport in January 1949. She was a horse riding instructor and stable hand who, in the years prior to the bombing, had divided her time between Wiltshire, England and Dundalk, Ireland. In 1971, she is known to have enlisted in the Women's Royal Army Corps, spending some time at Catterick Garrison, before going absent without leave and returning to Dundalk.[44]

In the weeks prior to her arrest, Ward had lived somewhat of a nomadic lifestyle; alternately sleeping rough around Euston railway station and hitchhiking to locations such as Cardiff to temporarily sleep at the house of an acquaintance. She had hitchhiked to Liverpool shortly before her arrest, and was planning to travel to Ireland when arrested.[n 6]

Although in her confession, Ward claimed to have conducted a string of bombings in Britain in 1973 and 1974, to have been married to a deceased IRA member, and to have borne a child to another IRA member, she had no affiliations with the IRA. An IRA spokesman later issued a statement confirming this fact.[45] Furthermore, Ward was known to have suffered from a personality disorder.[24][46]

Trial

Ward was brought to trial, charged with the M62 coach bombing and two separate, non-fatal IRA attacks at Euston Railway Station and the National Defence College based in Latimer in September 1973 and February 1974 respectively. The prosecution case against Ward was almost completely based on weak circumstantial evidence and what was later described as "demonstrably wrong" scientific evidence which had been obtained via the Griess tests conducted by Dr Skuse.[47] Her confession—which Ward had retracted prior to her trial—was also manipulated and distorted by some members of the investigating team,[47] but was presented at trial as being "backed up by overwhelming scientific evidence".[48]

Conviction

Despite irrefutable proof backed by over a dozen independent witnesses that Ward had been drinking in the Blue Boar pub in Chippenham, Wiltshire at the time of the bombing,[49] her subsequent retraction of her claims to have conducted several bombings throughout the previous year,[50] the lack of any corroborating evidence against Ward, and serious gaps in her testimony – which was frequently rambling, incoherent and "improbable"[51] – she was wrongfully convicted of the bombings in November 1974[52] and sentenced to a serve twelve concurrent terms of life imprisonment in relation to each of the fatalities of the coach bombing, plus thirty years' imprisonment.[53]

Ward did not appeal her conviction, although she repeatedly protested her innocence.[47] Although the validity of her conviction was independently reviewed on three occasions between 1985 and 1989, and each review uncovered serious flaws in both the evidence presented at trial and legal conduct, she remained incarcerated at HM Prison Durham before being transferred to HM Prison Holloway in November 1990.[48]

IRA statement

Formal statement issued by the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau following Judith Ward's conviction for the M62 coach bombing. 1974.[54]

Shortly after Ward's conviction for the M62 coach bombing, the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau issued a formal statement pertaining to her arrest and conviction. This statement again emphasised that Ward had not been a member of the IRA and that she had taken no role in any of the activities for which she had been convicted.[54]

Court of Appeal hearing

In May 1992, Ward's lawyers illustrated the fundamental flaws in the physical evidence presented at her 1974 trial before three Court of Appeal judges. Her barrister, Michael Mansfield, QC, contended there had been a "significant and substantial non-disclosure" of evidence and information which had strongly indicated her innocence, and that of the 63 interviews West Yorkshire Police had conducted with Ward before and after her confession, only 34 had been disclosed.[48] Furthermore, at this hearing, the court heard that the handling of lacquers or boot polish by any individual would produce the same positive results presented at Ward's trial as proof of her having handled explosive substances. This information had also never been disclosed at her original trial.[55]

All the evidence presented at Ward's appeal indicating her innocence had not been presented either to her original defence counsel, or before the court at her original trial. The Crown also heard that Ward's confession had been obtained under extreme duress and that, at the time of her provably false confession, she suffered from a personality disorder.[24][31]

The Court of Appeal ruled unanimously the conviction of Judith Ward was "a grave miscarriage of justice"[56] and conceded her confession had ultimately been obtained by law enforcement personnel "under pressure to [obtain] a confession" from an individual regarding his or her culpability in the atrocity.[57][58] Delivering final judgment at the conclusion of these appeal hearings, Lord Justice Iain Glidewell stated: "Our law does not permit a conviction to be secured by ambush."[59][n 7]

Release

Ward was released on bail, pending the conclusion of the legal proceedings of her appeal,[55] on 11 May 1992. She exited the courtroom to a positive public reaction, having wrongly served over seventeen years' imprisonment. Although Ward was the first of eighteen innocent English and Irish nationals known to have been falsely convicted of IRA atrocities, she was the last to be released from custody.[55][n 8]

Upon exiting the court, Ward shouted to all present, "Eighteen years! Freedom! After eighteen years, it's brilliant!" before being driven to a secret, safe address pending the conclusion of the legal hearings. Shortly thereafter, her conviction was formally overturned. She was later compensated for her wrongful conviction.[60]

| ""It looks as though there's a whole family who lost their lives there, including two children. There's one aged two and one aged five ... Twenty-eight is the oldest on there, going right down to the two children, which is quite sad."[25] |

| Jenny Berry, employee of Hartshead Moor service station, referencing the names and ages of the fatalities of the M62 coach bomb. October 2014. |

Aftermath

The most enduring consequence of the M62 coach bombing was the adoption of much stricter anti-terrorism laws in Great Britain and Northern Ireland.[61] These laws allowed police to hold individuals suspected of terrorism for up to seven days without charge, and to deport these individuals to Northern Ireland to face trial, where special courts with specific rules applying to terrorism suspects were based.[62]

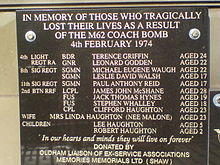

A memorial to those who were killed was later erected at Hartshead Moor service station, where many of the casualties of the M62 coach bombing had received impromptu first aid following the explosion.[32] Following a campaign by relatives of the deceased, a larger memorial was later erected several yards away from the entrance hall to the service station, close to an English oak tree planted in 2009 in memory of the deceased. This memorial stone also bears a memorial plaque inscribed with the names of those who died.[63][64][65]

The service station itself is the venue for annual memorial services commemorating those killed, injured and bereaved by the atrocity. These annual services are regularly attended by the Mayors of Kirklees, Calderdale and Oldham in addition to members of the Royal British Legion.[18][66]

A memorial plaque engraved with the names and ages of the fatalities of the M62 coach bomb was also unveiled in Oldham, the home town of two of the fatalities, in 2010.[67]

Judith Ward initially struggled with life as a free woman following the overturning of her conviction, in part because of the lack of a support structure she received from society after she had been formally exonerated. In 1996, Ward recollected to a reporter that, immediately prior to her release from prison, she was simply "given £35 and a hand-written note to produce at [the] DSS" before being released from custody with no individuals to offer advice, therapy, or other forms of support. As had earlier been the case with Gerry Conlon of the Guildford Four, Ward initially resided with solicitor Gareth Peirce until a secure home could be found for her.[68]

Ward later wrote an autobiography, Ambushed: My Story, detailing her life, conviction, exoneration, and subsequent experiences following her release from prison. She later became a campaigner for prisoners' rights with the Britain and Ireland Human Rights Centre.[68]

In October 1985, Dr Frank Skuse was ordered by the Home Office to retire on the grounds of "limited efficiency". Within a year of his retirement, all 350 cases in which Skuse had provided forensic evidence throughout his career had been reassessed.[69]

The actual perpetrator or perpetrators of the M62 coach bombing were never arrested or convicted.[15] Following the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the perpetrator(s) are guaranteed immunity from prosecution.[25]

See also

- Chronology of Provisional Irish Republican Army actions (1970–79)

- List of miscarriage of justice cases

Notes

- ^ Some sources state the bomb weighed 50 pounds (22 kg).[4]

- ^ The site where the bomb exploded is between Birstall and Birkenshaw.[18]

- ^ Handley's actions in steering the bombed coach to safety were later commended. He died at the age of 76 in January 2012.[23]

- ^ The sole member of the British Armed Forces to die in the M62 coach bombing not to hail from Greater Manchester was 22-year-old Gunner Leonard Godden, who hailed from Kent.[28]

- ^ The Haughton family are buried in Blackley Cemetery, Manchester.[30]

- ^ Ward would later claim to have briefly "flirted" with the general concept of Irish republicanism while in Dundalk, but to have neither formed any contacts with IRA members, or to have assisted with any IRA activities.[44]

- ^ A subsequent ruling would as a result of these hearings would mandate an absolute rule of disclosure regarding all material evidence obtained against a defendant.[59]

- ^ The flawed evidence in the case presented against Ward was similar to that presented in the convictions of the Guildford Four, the Birmingham Six and the Maguire Seven, each of which occurred shortly after Ward's arrest and conviction and all of which involved similar forged confessions and inaccurate scientific analysis conducted by Dr Skuse.[47]

References

- ^ "Memorial Service Remembers the Victims of M62 Coach Bombing 45 Years On". The Halifax Courier. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Sutton, Malcolm. "CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths". cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Responsible for Wrongful Jailing of Guildford Four". The Irish Times. 7 April 2001. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles ISBN 978-1-840-18504-1 p. 434

- ^ "False Confessions and Dodgy Evidence: The Innocent Inmates Locked up For Years in Yorkshire". Leeds Live. 20 September 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "M62 Bomb Blast Memorial Unveiled". BBC News. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "IRA Groupie Jailed for Coach Bomb Sought Folklore Fame". The Guardian. 22 March 1991. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Regina v Ward (Judith): CACD 15 Jul 1992". swarb.co.uk. 25 November 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "'There are Times When I Wish I Was Back in Jail'". The Independent. 1 October 1996. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Hunt for Relatives of IRA's Victims". Manchester Evening News. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Changes in Relation to Miscarriage of Justice". lawteacher.net. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ "BBC: Examining Justice in the UK". BBC News. 13 September 2005. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Tragedy On The M62". BBC News. 17 April 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "M62 IRA Coach Bombing: True Love Story, But Linda and Cliff Died With Their Sons in Attack". Belfast Newsletter. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Relatives of IRA Bombing Which Killed 12 Gather at Hartshead Moor for Poignant Memorial Ceremony". Yorkshire Live. 4 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "M62 Coach Bombing 40th Anniversary Marked". BBC News. 4 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Paddock, Andrew (10 April 2013). "M62 Coach Bombing". palacebarracksmemorialgarden.co.uk. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "Remembering Victims of M62 Coach Bomb". Batley & Birstall News. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Terrorist Blast: Eleven Die as Bus Blown Up". The Canberra Times. 5 February 1974. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ a b p. 240, Williams & Head

- ^ "Martin McGuinness: The Irish Peace Process". 1 January 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Hero Driver of M62 Coach Bombing Honoured with Memorial". Manchester Evening News. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "Hero Driver of M62 Coach Bombing Honoured With Memorial". Manchester Evening News. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles ISBN 978-1-840-18504-1 p. 435

- ^ a b c d "The M62". BBC News. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "M62 Coach Bomb Survivors Sought For New Memorial". Oldham Evening Chronicle. 19 January 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Tributes Paid to M62 Coach Bomb Victims 40 Years On". The Huddersfield Daily Examiner. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ "M62 Coach Bombing: Roll of Honour". palacebarracksmemorialgarden.co.uk. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "M62 Bomb Victims Honoured". The Oldham Chronicle. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Corporal Clifford Haughton" (PDF). nivets.org.uk. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Miscarriages of Justice". The Guardian. 15 January 2002. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Tragedy On The M62". BBC Bradford and West Yorkshire. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ "Miscarriages of Justice". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ "Her Body Simply Disintegrated in Our Arms". Sunday Business Post. 14 December 2003. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ p. 241, Williams & Head

- ^ "Bus Bombing: Houses Raided During Search". The Canberra Times. 6 February 1974. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "Tribute to Coach Bomb Victims". The Oldham Chronicle. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "1974: Soldiers and Children Killed in Coach Bombing". BBC News. 4 February 2005. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ p. 150, McGladdery

- ^ "Stair na hÉireann: History of Ireland". stairnaheireann.net. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Ward, Judith. "Ambushed: My Story". lrb.co.uk. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ An Gael - Volume 6, Issue 2 (1989) p. 7

- ^ The Birmingham Bombs ISBN 978-0-859-92070-4 p. 31

- ^ a b "Responsible for Wrongful Jailing of Guildford Four". The Irish Times. 7 April 2001. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ May, Paul. "'Buried Alive': The Case of Judy Ward 25 Years On". thejusticegap.com. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Kennedy, Helena (31 March 2011). Eve Was Framed: Women and British Justice. Random House. ISBN 9781446468340. Retrieved 17 June 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Schurr, Beverley (1993). "Expert Witnesses and The Duties Of Disclosure & Impartiality: The Lessons Of The IRA Cases In England" (PDF). Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "Nightmare On Disclosure Street" (PDF). newlawjournal.co.uk. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ May, Paul. "'Buried Alive': The Case of Judy Ward 25 Years On". thejusticegap.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "1974: Soldiers and Children Killed in Coach Bombing". BBC On This Day. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ In the words of her barrister Andrew Rankin QC, p. 242 Williams & Head

- ^ "40th Anniversary of M62 Coach Bomb Tragedy". ITV. 2 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "UK:Miscarriages of justice". statewatch.org. 1 September 1991. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b p. 89 McGladdery,

- ^ a b c "IRA 'Bomber' Freed After Eighteen Years". The Canberra Times. 13 May 1992. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ p. 244 Williams & Head

- ^ "Wrongly Jailed in UK May Not Get Redress". The Irish Times. 5 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles ISBN 978-1-840-18504-1 pp. 434-435

- ^ a b "Hidden Evidence". The Independent. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Britain Frees Woman After 18 Years in Jail". Tampa Bay Times. 12 May 1992. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Tributes Paid to M62 Coach Bomb Victims 40 Years On". Yorkshire Live. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ p. 245 Williams & Head

- ^ "New Tribute to Bomb's Victims; M62 Atrocity Recalled After 35 Years". Huddersfield Daily Examiner. 2008.

- ^ "Plans to Move Bomb Blast Memorial". BBC News. 29 July 2008.

- ^ "New Memorial Unveiled to Bus Bomb Victims". Bradford Telegraph and Argus. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "Service to Remember M62 Coach Bomb Victims". Halifax Couries. 5 February 2016.

- ^ Cooper, Louise (1 February 2015). "M62 Coach Bombing Victims Remembered 41 Years On At Memorial Service". Huddersfield Examiner. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ a b "'There Are Times When I Wish I Was Back in Jail'". The Independent. 1 October 1996. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Court Rekindles Memories of Carnage in Which 21 Died". The Glasgow Herald. 29 January 1988. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

Cited works and further reading

- Chalk, Peter (2012). The Encyclopedia of Terrorism – Volume 1. BC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-30895-6.

- Davis, Jennifer (2013). Wrongly Convicted: Miscarriages of Justice. RW Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-909-28440-1.

- Geraghty, Tony (1998). The Irish War: The Hidden Conflict Between the IRA and British Intelligence. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-006-38674-2.

- Gibson, Brian (1976). The Birmingham Bombs. Rose Publishing. ISBN 978-0-859-92070-4.

- Kudriavcevaite, Lina (2018). Miscarriages of Justice. The Case of Judith Ward. Verlag. ISBN 978-3-668-62870-0.

- McGladdery, Gary (2006). The Provisional IRA in England: The Bombing Campaign 1973–1997. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-7165-3374-0.

- Moysey, Steve (2019). The Road to Balcombe Street: The IRA Reign of Terror in London. Taylor & Francis Publishing. ISBN 978-1-136-74858-5.

- Robins, Jon (2018). Guilty Until Proven Innocent: The Crisis in Our Justice System. Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-785-90390-8.

- Ward, Judith (1993). Ambushed: My Story. Vermilion Press. ISBN 978-0-091-77820-0.

- Williams, Anne; Head, Vivian (2006). Terror Attacks: The Violent Expression of Desperation – IRA Coach Bomb. Futura. ISBN 0-7088-0783-6.

- Wilson, Colin (1985). Encyclopedia of Modern Murder 1962–1982. Bonanza Books. ISBN 978-0-517-66559-6.

External links

- Archive footage of the M62 coach bombing

- BBC news article pertaining to the M62 coach bombing

- 2009 news article listing names and ages of the survivors of the M62 coach bombing

- UK Cases: Judith Theresa Ward: Details of Ward's background and her subsequent confession to police

- 2019 Yorkshire Post article focusing upon the M62 coach bombing and subsequent conviction of Judith Ward

- Uniting Innocent Victims: A South East Fermanagh Foundation article detailing personal stories relating to the victims and survivors of global terrorism, including those killed, wounded and bereaved in the Troubles