Gay men are male homosexuals, or men whose sexual identity or sexual behavior is predominantly directed toward other men. Some bisexual and homoromantic men may also dually identify as gay men, and a number of young gay men today also identify as queer.[1] Historically, gay men have been referred to by a number of different terms, including sodomites, inverts, and Uranians, as well as a large number of slurs, including pansy, fairy, nelly, and sissy.

Gay men today continue to face significant discrimination in large parts of the world, including in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. In the United States, many gay men still face discrimination in their daily lives,[2] though some openly gay men have reached national success and prominence, including Tim Cook and Pete Buttigieg. In Europe, three gay men currently serve as Heads of State: Elio Di Rupo (Belgium), Xavier Bettel (Luxembourg), and Leo Varadkar (Ireland).

For a time, the term gay was used as a synonym for anything related to homosexual men. For example, the term "gay bar" still often refers to a bar which caters primarily to a homosexual male clientele or is otherwise part of gay men's culture. By the end of the 20th century, however, the word "gay" was recommended by LGBT groups and style guides to describe all people attracted to members of the same sex,[3] while "lesbian" referred specifically to female homosexuals, and "gay men" referred exclusively to male homosexuals.[4]

Male homosexuality in world history

Some scholars argue that the terms "homosexual" and "gay" are problematic when applied to men in ancient cultures since, for example, neither Greeks or Romans possessed any one word covering the same semantic range as the modern concept of "homosexuality".[5][6] Furthermore, there were diverse sexual practices that varied in acceptance depending on time and place.[5] Other scholars argue that there are significant similarities between ancient and modern male homosexuals.[7][8]

In cultures influenced by Abrahamic religions, the law and the church established sodomy as a transgression against divine law or a crime against nature. The condemnation of anal sex between males, however, predates Christian belief.[9] Many historical figures, including Socrates, Lord Byron, Edward II, and Hadrian,[10] have had terms such as gay or bisexual applied to them. Some scholars, such as Michel Foucault, have regarded this as risking the anachronistic introduction of a contemporary construction of sexuality foreign to their times,[11] though other scholars challenge this.[12][8][7]

Africa

The first record of a possible homosexual male couple in history is commonly regarded as Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, an ancient Egyptian couple, who lived around 2400 BCE. The pair are portrayed in a nose-kissing position, the most intimate pose in Egyptian art, surrounded by what appear to be their heirs.[13] At around of 1240, the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer Abul Fada'il Ibn al-'Assal compiled a legal code known as Fetha Nagast. Written in Ge'ez language, Ibn al-'Assal referred his laws from apostolic writer and former laws of Byzantine Empire. Fetha Nagast was written in two parts: the first dealt with the Church hierarchy sacraments and connected to religious rites. The second concerned laity, civil administration such as family laws.[14] In 1960, when the government enacted the civil code of Ethiopia, it cited the Fetha Nagast as an inspiration to the codification commission.[15] More recently, the European colonization of Africa resulted in the introduction of anti-sodomy laws, and is generally regarded as the central reason why African nations have such stringent laws against gay men today.[16] Three countries or jurisdictions have imposed the death penalty for gay men in Africa. These include Mauritania and several regions in Nigeria and Jubaland.[17][18][19]

Americas

As is true of many other non-Western cultures, it is difficult to determine the extent to which Western notions of sexual orientation apply to Pre-Columbian cultures. Evidence of homoerotic sexual acts between men has been found in many pre-conquest civilizations in Latin America, such as the Aztecs, Mayas, Quechuas, Moches, Zapotecs, the Incas, and the Tupinambá of Brazil.[20][21][22] The Spanish conquistadors expressed horror at discovering sodomy openly practiced among native men and used it as evidence of their supposed inferiority.[23] The conquistadors talked extensively of sodomy among the natives to depict them as savages and hence justify their conquest and forced conversion to Christianity. As a result of the growing influence and power of the conquistadors, many Native leaders started condemning homosexual acts themselves. During the period following European colonization, homosexuality was prosecuted by the Inquisition, sometimes leading to death sentences on the charges of sodomy, and the practices became clandestine. Many homosexual men went into heterosexual marriages to keep appearances, and some turned to the clergy to escape public scrutiny.[24]

During the Mexican Inquisition, after a series of denunciations, authorities arrested 123 men in 1658 on suspicion of homosexuality. Although many escaped, the Royal Criminal Court sentenced fourteen men from different social and ethnic backgrounds to death by public burning, in accordance to the law passed by Isabella the Catholic in 1497. The sentences were carried out together on one day, 6 November 1658. The records of these trials and those that occurred in 1660, 1673 and 1687, suggest that Mexico City, like many other large cities at the time had an active underworld.[24][25]

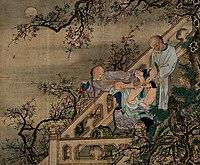

East Asia

In East Asia, same-sex relations between men has been noted since the earliest recorded history. Homosexuality in China, known as the passions of the cut peach and various other euphemisms, has been recorded since approximately 600 BCE. Male homosexuality was mentioned in many famous works of Chinese literature. The instances of same-sex affection and sexual interactions described in the classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber seem as familiar to observers in the present as do equivalent stories of romances between heterosexual people during the same period. Confucianism, being primarily a social and political philosophy, focused little on sexuality, whether homosexual or heterosexual. Ming dynasty literature, such as Bian Er Chai (弁而釵/弁而钗), portray homosexual relationships between men as more enjoyable and more "harmonious" than heterosexual relationships.[26] Writings from the Liu Song Dynasty by Wang Shunu claimed that homosexuality was as common as heterosexuality in the late 3rd century China.[27] Opposition to male homosexuality in China originates in the medieval Tang Dynasty (618–907), attributed to the rising influence of Christian and Islamic values,[28] but did not become fully established until the Westernization efforts of the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China.[29]

Europe

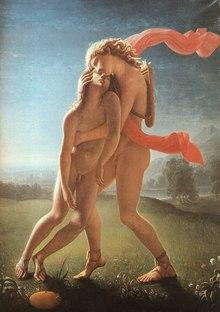

Classical period

The earliest Western documents (in the form of literary works, art objects, and mythographic materials) concerning same-sex male relationships are derived from ancient Greece. These relationships were constrained between "normal" men and their young male lovers. Relationships between adult men, however, were still largely considered taboo in Ancient Greek culture. Given the importance in Greek society of cultivating the masculinity of the adult male and the perceived feminizing effect of being the passive partner, relations between adult men of comparable social status were considered highly problematic, and usually associated with social stigma.[30]

This stigma, however, was reserved for only the passive partner in the relationship. According to contemporary opinion, Greek men who took on a passive sexual role after reaching adulthood – at which point they were expected to take the reverse role in pederastic relationships and become the active and dominant member – thereby were feminized or "made a woman" of themselves. There is ample evidence in the theater of Aristophanes that derides these passive men and gives a glimpse of the type of biting social opprobrium and shame ("atimia") heaped upon them by their society.[31]

Some scholars argue that there are examples of male homosexual love in ancient literature, such as Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad.[32] In Ancient Rome, the young male body remained a focus of male sexual attention, but relationships were between older free men and slaves or freed youths who took the receptive role in sex. The Hellenophile emperor Hadrian is renowned for his relationship with Antinous, but the Christian emperor Theodosius I decreed a law on 6 August 390, condemning passive males to be burned at the stake.[33][34]

Renaissance

During the Renaissance, wealthy cities in northern Italy—Florence and Venice in particular—were renowned for their widespread practice of same-sex love, engaged in by a considerable part of the male population and constructed along the classical pattern of Greece and Rome.[35][36] But even as many of the male population were engaging in same-sex relationships, the authorities, under the aegis of the Officers of the Night court, were prosecuting, fining, and imprisoning a good portion of that population.

From the second half of the 13th century, death was the punishment for male homosexuality in most of Europe.[37] The relationships of socially prominent figures, such as King James I and the Duke of Buckingham, served to highlight the issue,[38] including in anonymously authored street pamphlets: "The world is chang'd I know not how, For men Kiss Men, not Women now;...Of J. the First and Buckingham: He, true it is, his Wives Embraces fled, To slabber his lov'd Ganimede" (Mundus Foppensis, or The Fop Display'd, 1691).

Middle East

In ancient Sumer, a set of priests known as gala worked in the temples of the goddess Inanna, where they performed elegies and lamentations.[39]:285 Gala took female names, spoke in the eme-sal dialect, which was traditionally reserved for women, and appear to have engaged in homosexual intercourse.[40] The Sumerian sign for gala was a ligature of the signs for "penis" and "anus".[40] One Sumerian proverb reads: "When the gala wiped off his ass [he said], 'I must not arouse that which belongs to my mistress [i.e., Inanna].'"[40] In later Mesopotamian cultures, kurgarrū and assinnu were male servants of the goddess Ishtar (Inanna's East Semitic equivalent), who dressed in female clothing and performed war dances in Ishtar's temples.[40] Several Akkadian proverbs seem to suggest that they may have also engaged in homosexual intercourse.[40] In ancient Assyria, male homosexuality was present and common; it was also not prohibited, condemned, nor looked upon as immoral or disordered. Some religious texts contain prayers for divine blessings on homosexual relationships.[41][42] The Almanac of Incantations contained prayers favoring on an equal basis the love of a man for a woman, of a woman for a man, and of a man for man.[43]

Gay men in modern Western history

The use of gay to mean a "homosexual" man was first used as an extension of its application to prostitution: a gay boy was a young man or adolescent serving male clients.[44] Similarly, a gay cat was a young man apprenticed to an older hobo and commonly exchanging sex and other services for protection and tutelage. The application to homosexuality was also an extension of the word's sexualized connotation of "uninhibited", which implied a willingness to disregard conventional sexual mores. In court in 1889, the prostitute John Saul stated: "I occasionally do odd-jobs for different gay people."[45]

Bringing Up Baby (1938) was the first film to use the word gay in an apparent reference to homosexuality. In a scene in which Cary Grant's character's clothes have been sent to the cleaners, he is forced to wear a woman's feather-trimmed robe. When another character asks about his robe, he responds, "Because I just went gay all of a sudden!" Since this was a mainstream film at a time, when the use of the word to refer to cross-dressing (and, by extension, homosexuality) would still be unfamiliar to most film-goers, the line can also be interpreted to mean, "I just decided to do something frivolous."[46]

In 1950, the earliest reference found to date for the word gay as a self-described name for male homosexuals came from Alfred A. Gross, executive secretary for the George W. Henry Foundation, who said in the June 1950 issue of SIR magazine: "I have yet to meet a happy homosexual. They have a way of describing themselves as gay but the term is a misnomer. Those who are habitues of the bars frequented by others of the kind, are about the saddest people I’ve ever seen."[47]

Gay men in the Holocaust

Gay men were one of the primary victims of the Nazi Holocaust. Historically, the earliest legal step towards the Nazi persecution of male homosexuality was 1871's Paragraph 175, a law passed after the unification of the German Empire. Paragraph 175 read: "An unnatural sex act committed between persons of male sex... is punishable by imprisonment; the loss of civil rights might also be imposed." The law was interpreted differently in Germany until April 23, 1880, when the Reichsgericht ruled that criminal homosexual acts involved either anal, oral, or intercrural sex between two men. Anything less (such as kissing and cuddling) were deemed harmless play.[48]

Franz Gürtner, the Reich Justice Minister amended Paragraph 175 to address "loopholes" in the law after the Night of the Long Knives. The 1935 version of Paragraph 175 declared "expressions" of homosexuality as prosecutable crimes. The most important change to the law was the definitional shift of male homosexuality from "An unnatural sex act committed between persons of male sex" to instead "A male who commits a sex offense with another male." This expanded the reach of the law to persecute gay men as a people group, rather than male homosexuality as a sexual act. Kissing, mutual masturbation and love-letters between men were now seen as legitimate reasons for the police to make arrests. The law never defined a "sex offence," leaving it to interpretation.[49]

Between 1933 and 1945, an estimated 100,000 men were arrested as homosexuals under the Nazi regime, of whom some 50,000 were officially sentenced. Most of these men served time in prison, while an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 were incarcerated in Nazi concentration camps. Rüdiger Lautmann argued that the death rate of homosexuals in concentration camps may have been as high as 60%. Gay men in the camps suffered an unusual degree of cruelty by their captors and were regularly used as the subjects for Nazi medical experiments as scientists tried to find a "cure" for homosexuality.[50]

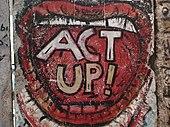

AIDS crisis in the United States

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is considered the deadliest period in modern history for gay men, and the generation of young gay men who died in the crisis is known as the "lost generation."[51] At its start, the epidemic was particularly severe in the United States. In 1980, San Francisco resident Ken Horne was reported to the CDC with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS). He was retroactively identified as the first patient of the AIDS epidemic in the US.[52] In 1981, Lawrence Mass became the first journalist in the world to write about the epidemic in the New York Native.[53] Later that year, the CDC reported a cluster of Pneumocystis pneumonia in five gay men in Los Angeles.[54] The next month, The New York Times ran the headline: "Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals."[55] The illness was soon termed Gay Related Immunodeficiency (G.R.I.D.), because it was believed to only affect gay men.[56] In June 1982, Larry Kramer founded the Gay Men's Health Crisis to provide food and support to gay men dying in New York City. During the early years of the AIDS crisis, gay men were treated pitilessly in hospital quarantine wards, left alone without contact for weeks at a time.[57]

.jpg)

During the early years of the epidemic, there was significant misinformation surrounding the illness. Rumors swirled that being in the same room or being touched by a gay man could lead one to contract HIV. It was not until April 1984 that the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler announced in a press conference that the American scientist Robert Gallo had discovered the probable cause of AIDS, the retrovirus which would be named human immunodeficiency virus or HIV. In September 1985, during his second term in office, US President Ronald Reagan publicly mentioned AIDS for the first time after being asked about his administration's lack of medical research funding for the crisis.[58][59] Four months later, Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, stated, "One million Americans have already been infected with the virus and that this number will jump to at least 2 million or 3 million within 5 to 10 years."[60] Gay men, trans women, and bisexual men faced the brunt of deaths during the first decade of the crisis. Activists claimed the government was responding to the epidemic with apathy because of the perceived "social undesirability" of these groups. To address this perceived apathy, activists such as Vito Russo, Larry Kramer, and others,[61] took more militant approaches to AIDS activism, organizing direct action through organizations like ACT UP in order to force pharmaceutical corporations and government agencies to respond to the epidemic with more urgency. ACT UP eventually grew into a transnational organization, with 140 chapters around the world,[62] while the AIDS crisis ultimately became a global epidemic. By 2019, complications related to AIDS had taken 32.7 million lives worldwide.[63]

Representations of gay men in Western media

In many forms of popular entertainment, gay men are portrayed stereotypically as promiscuous, flamboyant, flashy, and sassy. Gay men are also rarely the main characters in mainstream films; they frequently play the role of stereotyped supporting characters or are portrayed as either a victim or the villain.[64] There is currently a widespread view that depictions of gay men should be omitted from family-friendly entertainment and even from commercials which may be viewed by younger audiences. When such references do occur they almost invariably generate controversy.[65] Despite the stereotypical depictions of gay men, television shows since the 1990s, such as Queer as Folk, Queer Eye, and Modern Family have promoted broader social acceptance of gay men as "normal people." Nevertheless, gay men are still frequently portrayed in the United States as symbols of social decadence by evangelists and organizations such as Focus on the Family.[66]

Historical Western media representations

Historically, many films have included negative sub-texts regarding male homosexuality, such as in Alfred Hitchcock's films, whose villains used implied homosexuality to heighten senses of evil and alienation.[67] In news programming, male homosexuality was rarely directly mentioned, but it was often portrayed as a sickness, perversion, or crime. In 1967, CBC released a news segment on homosexuality; however, the segment was just a compilation of negative stereotypes of gay men.[68] The 1970s showed an increase in gay men's visibility in Western media with the 1972 ABC show That Certain Summer. The show was about a gay man raising a family, and although it did not show any explicit relations between the men, it contained no negative stereotypes.[68]

With the emergence of the AIDS epidemic and its associations to gay men, media outlets in the U.S. varied in their coverage, portrayal, and acceptance of gay male communities. The American Family Association, the Coalition for Better Television, and the Moral Majority organized boycotts against advertisers on television programs which showed gay men in a positive light.[69] Media coverage of gay men during the AIDS crisis depended on the location and therefore the local attitudes toward gay men. For example, in the Bay Area, The San Francisco Chronicle hired an openly gay man as a reporter and ran detailed stories on gay male topics. This was a sharp contrast to The New York Times, which refused to use the word "gay" in its writing, exclusively referring to gay men and lesbians with the term "homosexuals," because it was believed to be a more clinical term. The Times also limited its verbal and visual coverage of issues pertaining to gay men.[68][70]

Contemporary Western media representations

In recent years, positive representations of gay men entered mainstream television programming, however, critiques also emerged about the lack of diverse representations of gay men onscreen. Alfred Martin writes, "Popular television shows including Will & Grace, Sex and the City, Brothers and Sisters, and Modern Family routinely depict gay men. Yet the common characteristic among most televisual representations of gay men is that they are usually white."[71] Scholars have noted that intersectional representations of gay men of color are generally not present on television.[71] Additionally, when television shows do depict gay men of color, they are often used as a plot device or as some type of trope. For example, Blaine Anderson and Kurt Hummel were two important characters on the show Glee. Darren Criss, who portrays Blaine, is half-Asian, while Chris Colfer, who portrays Kurt, is white; Blaine often served as nothing more than a love-interest for Kurt's character. Gay male characters of color are also often depicted as "race neutral."[71] For example, on the ABC Family show, GRΣΣK, Calvin Owens is a Black, openly gay man; however, many of his storylines, plots, and struggles singularly revolve around his sexual identity. In an attempt to be colorblind, the show disregards his ethnic identity.[71]

Legal status of gay men in modern society

Africa

There are 54 nations in Africa recognized by either or both the United Nations or African Union. In 34 of these states, male homosexuality is explicitly outlawed.[72] In a 2015 report, Human Rights Watch noted that in Benin and the Central African Republic, male homosexuality is not explicitly outlawed, but both have laws which are applied differently for gay men than for straight men.[73] In Mauritania, northern Nigeria, Somaliland, and Somalia, male homosexuality is punishable by death.[72][74] In Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Uganda, gay men receive life imprisonment for homosexual acts, though the law is not regularly enforced in Sierra Leone. In Nigeria, legislation has also made it illegal for family members, allies, and friends of gay men to openly express support for homosexuality, and the country is generally recognized for its "cold-blooded" attitudes toward gay men.[75][76] Nigerian law states that any heterosexual person "who administers, witnesses, abets or aids" male homosexual activity should receive a 10-year jail sentence.[77] In Uganda, Christian fundamentalist organizations from the United States funded the introduction of Kill the Gays legislation to impose the death penalty for gay men.[78] The bill was ruled unconstitutional by the Ugandan Supreme Court in 2014, but retains support in the country and has been reconsidered for implementation.[79][80] Of all countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa has the most liberal attitudes toward gay men. In 2006, South Africa became the fifth country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage, and the Constitution of South Africa guarantees gay men and lesbians full equal rights and protections. South Africa is the only country in Africa where LGBT discrimination is constitutionally forbidden; however, social discrimination against South African gay men persists in rural parts of the country, where high levels of religious tradition continue to fuel prejudice and violence.[81]

Caribbean

.jpg)

In the Americas (both North and South), male homosexuality is legal in almost every country. In the Caribbean, however, nine nations have criminal punishment for "buggery" on their statute books.[72] These countries include: Barbados, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Dominica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Antigua and Barbuda, Guyana, and Jamaica. All nine of these countries are part of the former British West Indies. In Jamaica, sexual intercourse between men is legally punishable by imprisonment, though the law's repeal is pending. Like in Singapore, sexual intercourse between women is already legal.

In Jamaica, reports of vigilante violence and torture against gay men have been reported by the police. In 2013, Amnesty International reported, "Gay men and lesbian women have been beaten, cut, burned, raped and shot on account of their sexuality. ... We are concerned that these reports are just the tip of the iceberg. Many gay men and women in Jamaica are too afraid to go to the authorities and seek help."[83] As a result of this violence, hundreds of gay men from Jamaica sought to emigrate to countries with better human rights records.[84] A 2016 poll from J-Flag showed that 88 percent of those polled disapprove of homosexuality,[85] though since 2018, discriminatory attitudes have decreased slightly.[86]

In the Caribbean, like in other developing countries around the world, homosexual identity is often associated with Westernization,[87] and as a result, homophobia is believed to be an anti-colonial tool. Wayne Marshall writes, gay men are believed to be "decadent products of the West" and "are thus to be resisted alongside other forms of colonization, cultural or political."[88] Wayne cites the example of the Jamaican dancehall hit "Dem Bow" by Shabba Ranks, which calls for the violent murder of gay men alongside a call for the "freedom for Black people." Marshall notes the irony of this ideological position, considering the historical evidence that homophobia was introduced to colonies by European colonists.[89] Nevertheless, Caribbean scholars have noted the importance of opposition to gay men for Jamaican male gender construction. Kingsley Ragashanti Stewart, a professor of anthropology at the University of the West Indies, writes, "A lot of Jamaican men, if you call them a homosexual, ... will immediately get violent. It's the worst insult you could give to a Jamaican man."[90] Stewart writes that homophobia influences Caribbean society even at the micro level of language. He writes of urban youth vernacular, "It's like if you say, 'Come back here,' they will say, 'No, no, no don't say 'come back'.' You have to say 'come forward,' because come back is implying that you're 'coming in the back,' which is how gay men have sex."[90]

Eastern Europe

In Eastern Europe, there has been a steady erosion of rights for gay men over the course of the last decade. In Chechnya in the Chechen Republic, Russian Federation, gay men have been subjected to forced disappearances—secret abductions, imprisonment, torture—and extrajudicial killing by authorities. An unknown number of men, detained due to suspicion of them being gay or bisexual, have died while held in concentration camps.[91][92] Independent media and human rights groups have reported that gay men are being sent to clandestine camps in Chechnya, described by one eyewitness as "closed prison, the existence of which no one officially knows".[92][93] Some gay men have attempted to flee the region, but have been detained by Russian police and sent back to Chechnya.[94] Reports have emerged of prison officials releasing accused gay men from the camps after securing assurances from their families that their families will kill them (at least one man was reported by a witness as having died after returning to his family).[93] These men are kept in extremely cramped conditions, with 30 to 40 people are detained in one room (two to three metres big), and few are afforded a trial. Witnesses have also reported that the gay men are regularly beaten (with polypropylene pipes below the waist), tortured with electricity, and spat in the face by prison guards.[93] In some cases the process of torture has resulted in the death of the person being tortured.[95][96] As of 2021, the situation in Chechnya continues to worsen for gay men.[97] In other countries in Eastern Europe, rights for gay men continue to deteriorate. Polish President Andrzej Duda has pledged to ban teaching about gay men in schools, forbid same-sex marriage and adoption, and establish "LGBT-free zones."[98]

Southwest Asia and North Africa

In Southwest Asia and North Africa, gay men face some of the harshest and most hostile laws anywhere in the world. Sex between men is explicitly outlawed in 10 of the 18 "Middle Eastern" countries and is punishable by death in six. According to scholars, recent popular turns toward religious fundamentalism has strongly influenced the extreme violence against gay men. While all same-sex activity is legal in Bahrain, Cyprus, the West Bank, Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and Iraq, male homosexuality is illegal and punishable by imprisonment in Syria, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait, and Egypt. Male same-sex activity is also punishable by death in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Qatar. In the Gaza Strip and Yemen, punishment for male homosexuality varies between death and imprisonment depending on the act committed. In 2018, a transnational survey conducted in the region by Pew Research Center found that 80% of people polled believed homosexuality was "morally unacceptable,"[99] though others argue that the true number of people who support rights for gay men is unclear due to fear of backlash and punishment.[100]

See also

- History of gay men in the United States

- Gay

- Gay characters in fiction

- Gay male speech

- Lesbian

- LGBT

- List of gay, lesbian or bisexual people

- Trans man

References

- ^ Goldberg, Shoshana K.; Rothblum, Esther D.; Meyer, Ilan H.; Russell, Stephen T. "Who Identifies as Queer? A Study Looks at the Partnering Patterns of Sexual Minority Populations". American Psychological Association. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "The Effects of Negative Attitudes on Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men". CDC. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Avoiding Heterosexual Bias in Language". American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015. (Reprinted from American Psychologist, Vol 46(9), Sep 1991, 973-974 Archived 3 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "GLAAD Media Reference Guide - Terms To Avoid". GLAAD. 25 October 2016. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ a b Hubbard, Thomas K. (2003). "Introduction". Homosexuality in Greece and Rome : a Sourcebook of Basic Documents. University of California Press. p. 1. ISBN 0520234308.

The term "homosexuality" is itself problematic when applied to ancient cultures, inasmuch as neither Greek nor Latin possesses any one word covering the same semantic range as the modern concept. The term is adopted in this volume not out of any conviction that a fundamental identity exists between ancient and modern practices or self-conceptions, but as a convenient shorthand linking together a range of different phenomena involving same-gender love and/or sexual activity. To be sure, classical antiquity featured a variety of discrete practices in this regard, each of which enjoyed differing levels of acceptance depending on the time and place.

- ^ Larson, Jennifer (6 September 2012). "Introduction". Greek and Roman Sexualities : A Sourcebook. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 15. ISBN 978-1441196859.

There is no Greek or Latin equivalent for the English word 'homosexual', although the ancients did not fail to notice men who preferred same-sex partners.

- ^ a b Norton, Rictor (2016). Myth of the Modern Homosexual. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781474286923. The author has made adapted and expanded portions of this book available online as A Critique of Social Constructionism and Postmodern Queer Theory.

- ^ a b Boswell, John (1989). "Revolutions, Universals, and Sexual Categories" (PDF). In Duberman, Martin Bauml; Vicinus, Martha; Chauncey, Jr., George (eds.). Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. Penguin Books. pp. 17–36. S2CID 34904667.

- ^ "... sow illegitimate and bastard seed in courtesans, or sterile seed in males in defiance of nature." Plato in THE LAWS (Book VIII p.841 edition of Stephanus) or p.340, edition of Penguin Books, 1972.

- ^ Roman Homosexuality By Craig Arthur Williams, p.60

- ^ (Foucault 1986)

- ^ Hubbard Thomas K (22 September 2003). "Review of David M. Halperin, How to Do the History of Homosexuality.". Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

- ^ Richard Parkinson: Homosexual Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature. In: The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology (JEA), vol. 81, 1995, pp. 57–76.

- ^ Strauss, Peter L. (ed.). The Fetha Nagast: The Law of the Kings (PDF). Translated by Tzadua, Abba Paulos. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: The Faculty of Law, Haile Sellassie I University. p. xxix.

- ^ Dominic, Negussie Andre (2010). The Fetha Nagast and Its Ecclesiology: Implications in Ethiopian Catholic Church today. European University Studies 23; Theology Volume 910. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-0343-0549-5. ISSN 0721-3409.

- ^ Buckle, Leah. "African sexuality and the legacy of imported homophobia". Stonewall. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Aengus Carroll; Lucas Paoli Itaborahy (May 2015). "State-Sponsored Homophobia: A World Survey of Laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition of same-sex love" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex association. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ Mendos, Lucas Ramón (2019). State-Sponsored Homophobia 2019 (PDF). Geneva: ILGA. p. 359.

- ^ "Here are the 10 countries where homosexuality may be punished by death". The Washington Post. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Pablo, Ben (2004), "Latin America: Colonial", glbtq.com, archived from the original on 11 December 2007, retrieved 1 August 2007

- ^ Murray, Stephen (2004). "Mexico". In Claude J. Summers (ed.). glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. glbtq, Inc. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ Sigal, Pete (2003). Infamous Desire: Male Homosexuality in Colonial Latin America. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226757049.

- ^ Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. (1530). Décadas del Mundo Nuevo. Quoted by Coello de la Rosa, Alexandre. "Good Indians", "Bad Indians", "What Christians?": The Dark Side of the New World in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557), Delaware Review of Latin American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2002.

- ^ a b Hamnett, Brian R. (1999). Concise History of Mexico. Port Chester NY USA: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 63–95. ISBN 978-0-521-58120-2.

- ^ Jose Rogelio Alvarez, ed. (2000). "Inquisicion". Enciclopedia de Mexico (in Spanish). VII (2000 ed.). Mexico City: Sabeca International Investment Corp. ISBN 1-56409-034-5.

- ^ Kang, Wenqing. Obsession: male same-sex relations in China, 1900–1950, Hong Kong University Press. Page 2

- ^ Song Geng (2004). The fragile scholar: power and masculinity in Chinese culture. Hong Kong University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-962-209-620-2.

- ^ Hinsch, Bret. (1990). Passions of the Cut Sleeve. University of California Press. p. 77-78.

- ^ Kang, Wenqing. Obsession: male same-sex relations in China, 1900–1950, Hong Kong University Press. Page 3

- ^ Meredith G. F. Worthen (10 June 2016). Sexual Deviance and Society: A Sociological Examination. Routledge. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-1-317-59337-9.

- ^ Oxford Classical Dictionary entry on homosexuality, pp.720–723; entry by David M. Halperin.

- ^ Morales, Manuel Sanz; Mariscal, Gabriel Laguna (2003). "The Relationship between Achilles and Patroclus according to Chariton of Aphrodisias". The Classical Quarterly. 53 (1): 292–295. doi:10.1093/cq/53.1.292. ISSN 0009-8388. JSTOR 3556498.

- ^ Skinner, Marilyn (2013). Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture. Ancient Cultures (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-4986-3.

- ^ Mackay, Christopher S. (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Rocke, Michael, (1996), Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and male Culture in Renaissance Florence, ISBN 0-19-512292-5

- ^ Ruggiero, Guido, (1985), The Boundaries of Eros, ISBN 0-19-503465-1

- ^ Kurtz, Lester R. (1999). Encyclopedia of violence, peace, & conflict. Academic Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-12-227010-X.

- ^ Bergeron, David M. (2002). "4: George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham". King James and Letters of Homoerotic Desire. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 9781587292729.

By all sensible accounts, Buckingham became James's last and greatest lover.

- ^ Leick, Gwendolyn (2013) [1994]. Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-92074-7.

- ^ a b c d e Roscoe, Will; Murray, Stephen O. (1997). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature. New York City, New York: New York University Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-8147-7467-9.

- ^ Gay Rights Or Wrongs: A Christian's Guide to Homosexual Issues and Ministry, by Mike Mazzalonga, 1996, p.11

- ^ The Nature Of Homosexuality, Erik Holland, page 334, 2004

- ^ Pritchard, p. 181.

- ^ Muzzy, Frank (2005). Gay and Lesbian Washington, D.C. Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0738517537.

- ^ Kaplan, Morris (1999). "Who's Afraid Of John Saul? Urban Culture and the Politics of Desire in Late Victorian London". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 5 (3): 267–314. doi:10.1215/10642684-5-3-267. S2CID 140452093. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Bringing Up Baby". Archived from the original on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 24 November 2005.

- ^ "The Truth About Homosexuals," Sir, June 1950, Sara H. Carleton, New York, p. 57.

- ^ Giles, Geoffrey J (2001). Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 240.

- ^ Giles, Geoffrey J. (2001). Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 240–242.

- ^ "Remembering LGBT people murdered in the Holocaust". Morning Star. 2020-01-27. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Dana. "The AIDS epidemic's lasting impact on gay men". The British Academy. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ KQED LGBT Timeline. Kqed.org. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^ Kinsella, James (1989). Covering the Plague: AIDS and the American Media. Rutgers University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780813514826.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control (June 1981). "Pneumocystis pneumonia--Los Angeles" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 30 (21): 250–2. PMID 6265753.

- ^ Lawrence K. Altman (July 3, 1981). "Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Altman, Lawrence K. "NEW HOMOSEXUAL DISORDER WORRIES HEALTH OFFICIALS". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Coker Burks, Ruth (December 2020). All The Young Men (1 ed.). New York City: Grove Press. ISBN 9780802157249.

- ^ "The President's News Conference, September 17, 1985". Archived from the original on 2016-09-24.

- ^ Boffey, Philip (1985-09-18). "Reagan Defends Financing for AIDS". The New York Times.

- ^ Boffey, Philip (1986-01-14). "AIDS IN THE FUTURE: EXPERTS SAY DEATHS WILL CLIMB SHARPLY". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ^ Anonymous. "Queers Read This". QRD. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "ACT UP 1987-2012". ACT UP NY. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2020 fact sheet". UN AID. United Nations. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Mazur, M. A., & Emmers-Sommer, T. M. (2002). "The Effect of Movie Portrayals on Audience Attitudes about Nontraditional Families and Sexual Orientation". Journal of Homosexuality. 44 (1): 157–179. doi:10.1300/j082v44n01_09. PMID 12856761. S2CID 35184339.

- ^ Gomstyn, Alex. "Banned Super Bowl Commercials". ABC News. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Stacey, Judith (March 2005). "The Families of Man: Gay Male Intimacy and Kinship in a Global Metropolis". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 30 (3): 1911-1935. doi:10.1086/426797. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Homosexuality in Hitchcock's Movies". Alfred Hitchcock Films. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Laermer, R. (February 5, 1985). "The Televised Gay: How We're Pictured on the Tube". The Advocate.

- ^ Moritz, M.J. (1992). "The Fall of our Discontent: The Battle Over Gays on TV". State of the Art: Issues in Contemporary Mass Communication.

- ^ Thomson, T.J. (2018). "From the Closet to the Beach: A Photographer's View of Gay Life on Fire Island From 1975 to 1983" (PDF). Visual Communication Quarterly. 25: 3–15. doi:10.1080/15551393.2017.1343152. S2CID 150001974.

- ^ a b c d Martin Jr, Alfred L. (Fall 2011). Julia Himberg (ed.). "TV in Black and Gay: Examining Constructions of Gay Blackness and Gay Crossracial Dating on GRΣΣK" (PDF). Spectator. 31 (2): 63–69.

- ^ a b c "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Ferreira, Louise (28 July 2015). "How many African states outlaw same-sex relations? (At least 34)". Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Boni, di Federico. "Sudan, cancellata la pena di morte per le persone omosessuali - Gay.it". www.gay.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ Akuson, Richard. "Nigeria is a cold-blooded country for gay men – I have the scars to prove it". CNN. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Adebayo, Bukola. "Nigeria is trying 47 men arrested in a hotel under its anti-gay laws". CNN. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "African Anti-Gay Laws". Laprogressive.com. 2014-02-20. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- ^ Wu, Tim. "Evangelizing Hatred". Slate. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Bhalla, Nita. "Uganda plans bill imposing death penalty for gay sex". Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Fitzsimons, Tim. "Amid 'Kill the Gays' bill uproar, Ugandan LGBTQ activist is killed". NBC News. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Daniels, Joseph (March 5, 2019). "Rural school experiences of South African gay and transgender youth". Journal of LGBT Youth (4): 355-379. doi:10.1080/19361653.2019.1578323. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Nelson, Leah. "Jamaica's Anti-Gay 'Murder Music' Carries Violent Message". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ "Jamaica's Gays: Protection from Homophobes Urgently Needed". Amnesty International, compiled by GayToday.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Gay Jamaican wins U.S. asylum". Qnotes Online. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Freedom in the World 2018 - Jamaica". Refworld. 27 August 2018. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ Faber, Tom. "Welcome to Jamaica – no longer 'the most homophobic place on Earth'". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Dangerous Living". First Run Features. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ Marshall, Wayne (2008). "Dem Bow, Dembow, Dembo: Translation and Transnation in Reggaetón". Song and Popular Culture. 53: 131–151. JSTOR 20685604.

- ^ Evaristo, Bernardine (2014-03-08). "The idea that African homosexuality was a colonial import is a myth". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ a b Fink, Micah (September 2009). "How AIDS Became a Caribbean Crisis". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Smith, Lydia (10 April 2017). "Chechnya detains 100 gay men in first concentration camps since the Holocaust". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Daniel (10 April 2017). "Report: Chechnya Is Torturing Gay Men in Concentration Camps". The Advocate. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ a b c "Расправы над чеченскими геями (18+)". Новая газета - Novayagazeta.ru. 4 April 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "Chechnya: Escaped gay men sent back by Russian police". BBC. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "People are being beaten and forced to 'sit on bottles' in anti-gay 'camps' in Chechnya". The Independent. 2017-04-11. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ^ "Chechnya has opened concentration camps for gay men". PinkNews. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ^ "Two Gay Men Returned to Chechnya Face 'Mortal Danger,' Rights Group Says". VOA. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Ash, Lucy. "Inside Poland's 'LGBT-free zones'". CNN. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ El Feki, Shereen (2015). "The Arab Bed Spring? Sexual Rights in Troubled times across the Middle East and North Africa". Reproductive Health Matters. 23 (46): 38–44. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.010. JSTOR 26495864. PMID 26718995 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Tomen, Bihter (2018). "Pembe Caretta: LGBT Rights Claiming in Antalya, Turkey". Journal of Middle East Women's Studies 14. 2: 255–258. doi:10.1215/15525864-6680400. S2CID 149701166 – via Project MUSE.

External links

- Gay men at Curlie

- Portraits of Gay Men in Love - Smithsonian Institution portrait photographs of gay men in the United States.

- Reported Effects of Masculine Ideals on Gay Men - National Institutes of Health report on masculine idealization

- Gay Bears at UC Berkeley - UC Berkeley history of the Gay Liberation Movement

- Interactive AIDS Memorial Quilt - National AIDS Memorial digital AIDS Memorial Quilt

- Gay Men's Health Crisis - GMHC website

- Gale Archive of Sexuality and Gender - archive related to the history of sexuality

.jpg)

.jpg)